Why did Frederick Douglass say he could not vote for Abraham Lincoln in 1860?

“The fusion of antislavery and antiracism left Douglass with no explanation for what happened in the 1850s. He correctly sensed the progress of antislavery among the mass of northern whites, but he looked away from the racism that intensified at the same time. To some extent these were parallel developments that reflected the polarization of the electorate: As one group of northerners grew more hostile to slavery another reacted with increasingly shrill racism.” –Oakes, 117

“I will say then that I am not now, nor have ever been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” —Abraham Lincoln, Charleston, Illinois, September 18, 1858

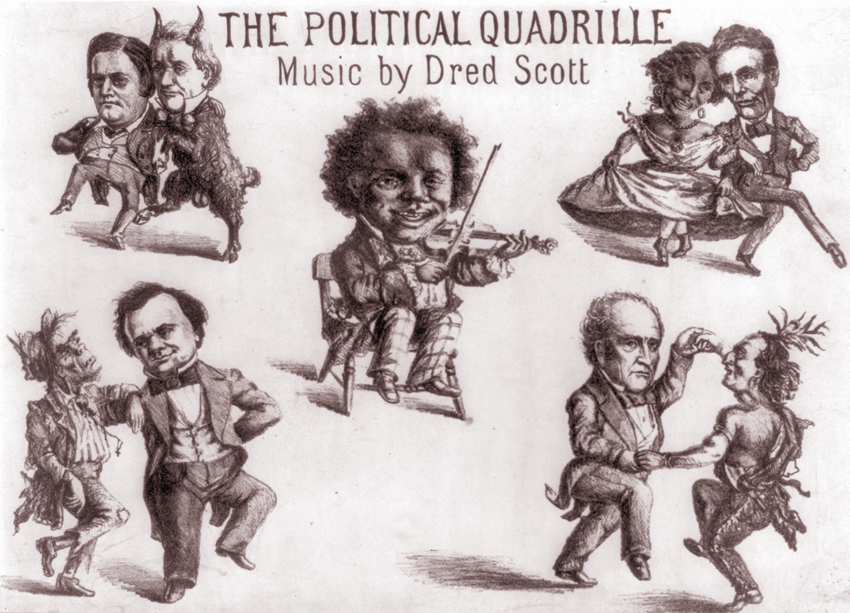

- NOTE: Dred Scott had died the day before

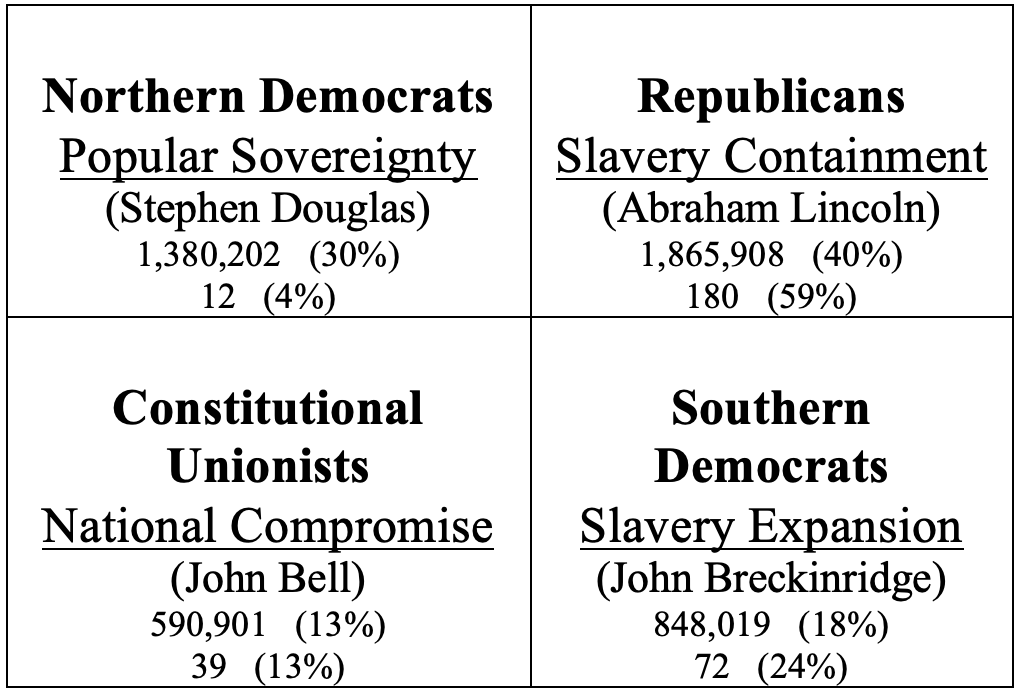

There were four main political parties vying for the 1860 victory. Students in History 211 should be able to identify all four factions. They should also know about the “fifth” party presidential candidate (Gerrit Smith, Radical Abolitionist or former Liberty party) whom Douglass said that he supported in 1860. One way to remember the complicated main four-way race is interpret the political cartoon above. Who are the four candidates dancing to Dred Scott’s “quadrille”? But students in History 211 also need to understand how the slavery issue was playing out in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Why was sectionalism growing more intense? Which side felt like they were prevailing? As the cartoon indicates, the legacy of the Dred Scott Decision still loomed large over the electorate, but another cartoon from the campaign also suggests that a different event was just as salient.

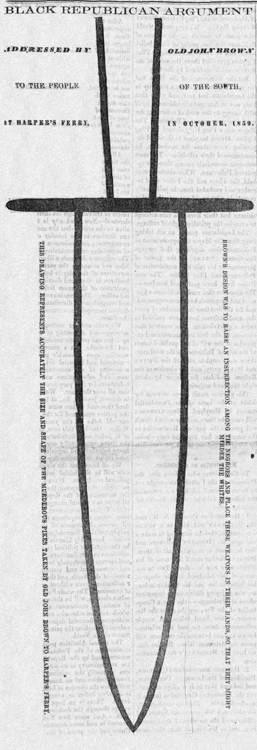

The image to the left, entitled “Black Republican Argument,” actually appeared in a Pennsylvania newspaper late in the campaign. The stark image depicts the use of John Brown’s Raid by southern Democrats. Brown was an abolitionist originally from Connecticut who had become notorious because of his actions in the Kansas Territory. Brown and his sons had been deeply involved in the battles of “Bleeding Kansas,” and he stood accused of murdering at least five pro-slavery settlers in cold blood. Brown, however, was a hero to many abolitionists and northern blacks who revered his fierce anti-slavery stance and his remarkably modern form of egalitarianism. James Oakes claims that Douglass revered Brown and that the black abolitionist “embraced the romance of revolutionary violence” by the end of the decade even though he declined to participate in the raid himself (Oakes, 101).

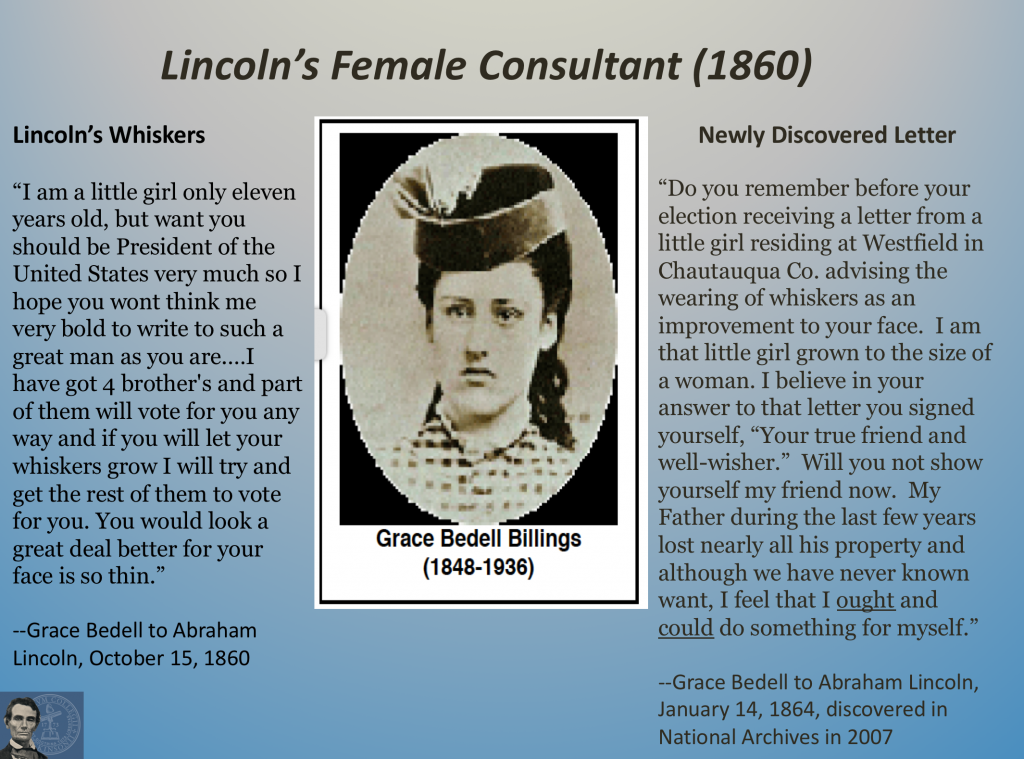

Lincoln certainly tried to separate Republicans from the stigma of Brown’s raid. But for most of the 1860 campaign, Lincoln himself was absent and quiet. Like most (but not all) presidential candidates of that era, Lincoln did not campaign openly for the office. According to his law partner, Lincoln was left feeling “bored –bored badly” by this tradition. His boredom, however, might help explain a fascinating exchange candidate Lincoln conducted with an eleven-year-old girl from New York in October 1860. Young Grace Bedell wrote Lincoln urging him to grow a beard because his face was “so thin.” Lincoln responded asking whether or not such a move might appear as an “affectation,” but within days after his November victory, Lincoln began growing the beard. Later, President-Elect Lincoln met the young girl and the two of them had an ongoing correspondence during the Civil War –although this fact was not known to scholars until very recently. The full story of the relationship is detailed here at the Blog Divided.

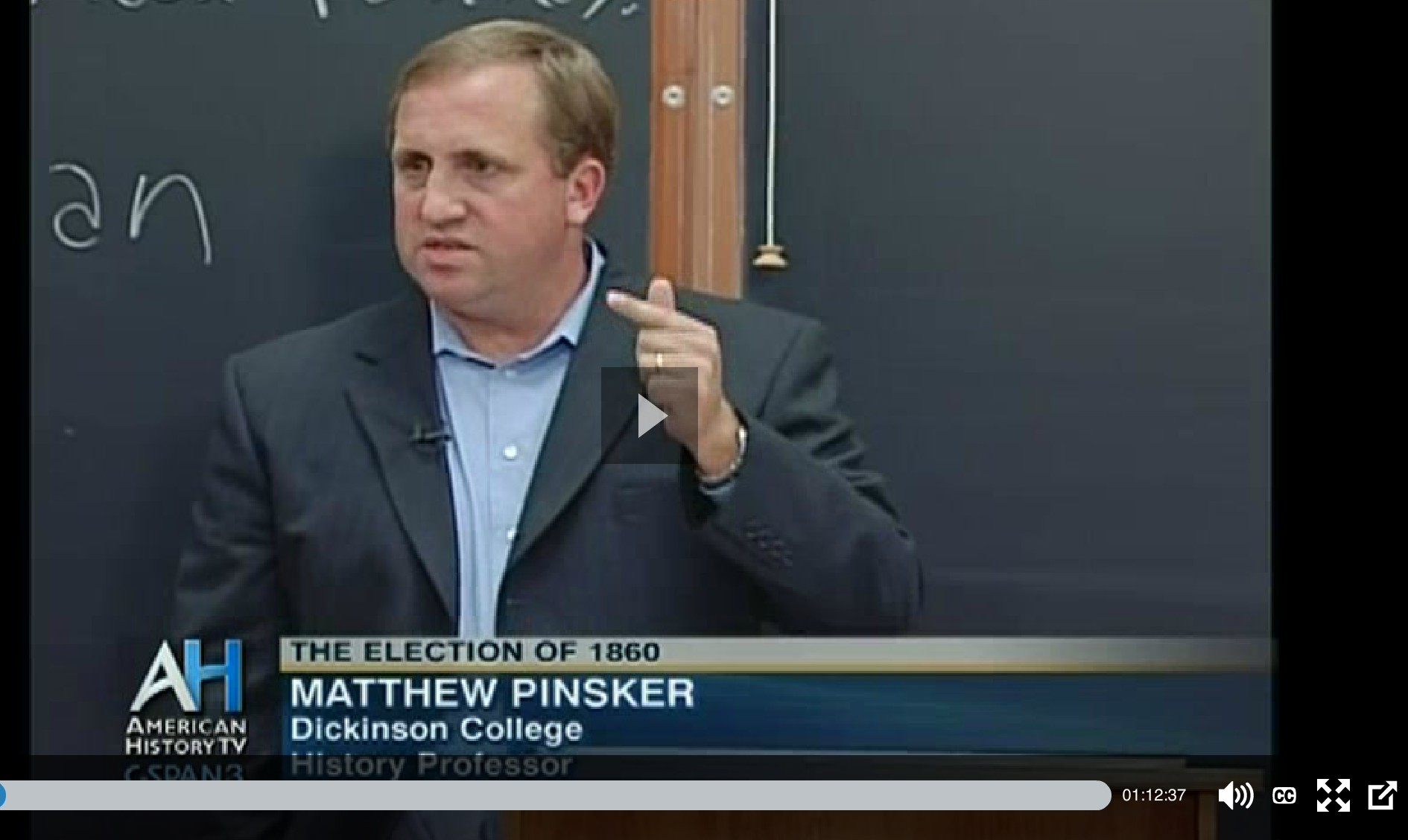

Thus, the 1860 contest stands alone in American history. Yet how should students best understand its meaning? In History 211, students will look carefully at the so-called “campaign” of Abraham Lincoln, through study of his 1859 autobiographical sketch and his October 1860 letter to a young girl named Grace Bedell. C-SPAN filmed a previous version of this particular class in 2010. You might want to check it out (and pay particular attention to the late student arriving at the beginning of the video…).

For those who need additional background on the contest, please check out the following resources:

- Chapter 13, “The Sectional Crisis,” American Yawp

- Election of 1860 results, American Presidency Project

- Man of Consequence: Lincoln in the 1850s, Dickinson Survey of American History

Close Reading exercise

Lincoln’s Autobiographical Sketch (1859)

Lincoln’s correspondence with Grace Bedell (1860 / 1864)