“Another danger is imminent – a contested result. And we have no such means for its decision as ought to be provided by law. This must be attended to hereafter. We should not be allowed another Presidential election to occur before a means for settling a contest is provided.” – Governor Rutherford B. Hays in October 1876

The election of 1876 has been agreed upon to be one of the most disputed elections in the history of the United States. On that Election Day, November 7, 1876, both political parties assumed that the Democratic Party had secured victory for the presidential race. The election was between two major politicians, Governor Samuel J. Tilden on the Democratic side and Governor Rutherford B. Hayes as the Republican nomination.

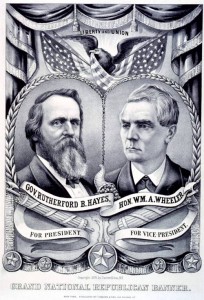

As a Whig, Governor Hayes’ platform stood for conservative and traditional values. He had been a defender of slaves and joined the Republican Party. His platform became vital as he served on Congress and supported the Southern Reconstruction. However, prior to 1876 and after many defeats in the political world, Hayes opted to retire from politics. The Republicans had a different plan for him though, and nominated him as their presidential ticket in the 1876 election with the running mate of William Wheeler.

On the one hand, Tilden had carried much of the South and his home state of New York; on the other hand, Hayes had held much of New England, the Midwest and many of the Western states.On the evening of the election, Hayes went to bed believing he had lost the presidency to Tilden quite handedly. He wrote in his diary, “I never supposed there was a chance for a Republican success.” Unaware to both candidates, the executive office was torn between just one electoral vote. Headlines across the country had even stated that Tilden had secured the victory. For many days, Hayes was not sure of the outcome of the race. Rumors of electoral fraud raged throughout the nation. The final electoral vote was Tilden with 184 and Hayes with 185. Without this knowledge, both parties considered themselves the winners. Both Hayes and Tilden lay low as their representatives dealt with the anticipating public.

To combat these growing controversies, the House and the Senate created an Electoral Commission with a company of fifteen people: seven Republicans seven and seven Democrats. Of these fifteen people, the makeup was: five senators, five house members and five Supreme Court justices.

Though Tilden had won the popular vote, the Commission swung in favor of Hayes. On March 2, 1877, the Commission finally announced that Hayes, with his running mate William Wheeler, were to be the new President and Vice President elect by an electoral vote of 185-184. But on that day of March 5, 1877, when President Hayes was finally inaugurated into office, he knew that his struggle was far from over. The Southern Democrats threatened radical action to be taken if Hayes did not meet their needs. In what C. Vann Woodward titled “The Compromise of 1877,” Hayes agreed to withdraw troops from the South, thus ending Reconstruction.

The Election of 1876 is extremely important to the electoral history of the United States. As one of the most disputed elections of recent history, it enabled the politicians of America to take action in the Post-Civil War era. Rurtherford B. Hayes’ role was subtle yet powerful as he stepped his way into the presidency over Samuel Tilden and the strong Democratic Party. Hayes kept calm and stayed in the background until he emerged and accepted the presidency after almost four months of debate.