Students in this course are required to create a final project that examines a significant American diplomat. Here are brief excerpts on about fifty leading US diplomatic figures culled from George Herring’s magisterial study, From Colony to Superpower (2008). Please note, however, that the profiles below exclude anyone who served as president, while otherwise embracing a very broad definition of diplomacy. Below you will find not only State Department officials and presidential advisors, but also businessmen, journalists, military officers, missionaries, politicians and even social activists –any American citizen who exerted significant influence, for good or bad, on U.S. foreign policy between 1776 and 2001. All of them represent good potential project topics for this course.

Dean Acheson (1893-1971)

“Of all the Wise Men, none was more controversial and influential than Dean Gooderham Acheson. The son of British and Canadian parents, Acheson was educated at Groton, Yale, and Harvard Law School. After clerking with legendary Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, he joined one of Washington’s most prestigious law firms. He entered the State Department in 1941, working mainly on economic issues. A large man, aristocratic in bearing and haughty in demeanor, he cute quite a figure with his heavy eyebrows, carefully waxed guardsman’s mustache (which one writer swore had a personality of its own), elegant suits, and Homburg hat. He was brilliant of mind and suffered fools poorly. A clever wordsmith, he did not hesitate to turn his acerbic wit on adversaries, which sometimes got him into trouble with Congress. He was certain that his nation had the power and the proper values to grasp the reigns of world leadership.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 613)

“Of all the Wise Men, none was more controversial and influential than Dean Gooderham Acheson. The son of British and Canadian parents, Acheson was educated at Groton, Yale, and Harvard Law School. After clerking with legendary Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, he joined one of Washington’s most prestigious law firms. He entered the State Department in 1941, working mainly on economic issues. A large man, aristocratic in bearing and haughty in demeanor, he cute quite a figure with his heavy eyebrows, carefully waxed guardsman’s mustache (which one writer swore had a personality of its own), elegant suits, and Homburg hat. He was brilliant of mind and suffered fools poorly. A clever wordsmith, he did not hesitate to turn his acerbic wit on adversaries, which sometimes got him into trouble with Congress. He was certain that his nation had the power and the proper values to grasp the reigns of world leadership.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 613)

Alvey Adee (1842-1924)

“The instruments of Gilded Age foreign policy reflected more the nation’s insular past than its global future. The State Department escaped the worst abuses of the era of spoilsmen, but its staff of eighty-one people remained small for an incipient world power. Work hours were a leisurely 9:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M.; the pace was very slow. State’s methods of operation dated to John Quincy Adams. Much of the work was done by a single person, the legendary Alvey Adee, a bureaucrat par excellence who served forty years as second assistant secretary of state. The State Department’s institutional memory and a master of diplomatic practice, Adee drafted most of its instructions and dispatches. ‘Why there isn’t a kitten born in a palace anywhere on earth that I don’t have to write a letter of congratulation to the peripatetic tomcat that might have been its sire,’ Theodore Roosevelt would later joke, ‘and old Adee does that for me!'” (Herring, chap. 7, p. 279)

“The instruments of Gilded Age foreign policy reflected more the nation’s insular past than its global future. The State Department escaped the worst abuses of the era of spoilsmen, but its staff of eighty-one people remained small for an incipient world power. Work hours were a leisurely 9:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M.; the pace was very slow. State’s methods of operation dated to John Quincy Adams. Much of the work was done by a single person, the legendary Alvey Adee, a bureaucrat par excellence who served forty years as second assistant secretary of state. The State Department’s institutional memory and a master of diplomatic practice, Adee drafted most of its instructions and dispatches. ‘Why there isn’t a kitten born in a palace anywhere on earth that I don’t have to write a letter of congratulation to the peripatetic tomcat that might have been its sire,’ Theodore Roosevelt would later joke, ‘and old Adee does that for me!'” (Herring, chap. 7, p. 279)

Madeleine Albright (1937-

“More important in terms of precedent –and policy– was the replacement of [Secretary of State Warren] Christopher with UN ambassador Madeleine Albright, the first female secretary of state. The daughter of a Czech diplomat who escaped both the Nazi invasion and the Communist takeover, Albright claimed to know the meaning of Munich firsthand. The United States, in her view, must take responsibility for upholding world order. She was consistently the most hawkish of Clinton’s advisers. ‘What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about,’ she once berated [General Colin] Powell, ‘if we can’t use it?’ Described as the ‘ultimate independent woman,’ she had raised three daughters before launching a career. She bristled when reporters wrote about her appearance. Effective on television and in public, she won points at the White House during the 1996 campaign by telling an appreciative Cuban-American audience in Miami’s Orange Bowl that the shooting down of civilian aircraft by Fidel Castro’s pilots was ‘not cojones but cowardice.’ By sheer force of personality, she became a key player, especially with regard to the Balkans.” (Herring, chap. 20, p. 932)

“More important in terms of precedent –and policy– was the replacement of [Secretary of State Warren] Christopher with UN ambassador Madeleine Albright, the first female secretary of state. The daughter of a Czech diplomat who escaped both the Nazi invasion and the Communist takeover, Albright claimed to know the meaning of Munich firsthand. The United States, in her view, must take responsibility for upholding world order. She was consistently the most hawkish of Clinton’s advisers. ‘What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about,’ she once berated [General Colin] Powell, ‘if we can’t use it?’ Described as the ‘ultimate independent woman,’ she had raised three daughters before launching a career. She bristled when reporters wrote about her appearance. Effective on television and in public, she won points at the White House during the 1996 campaign by telling an appreciative Cuban-American audience in Miami’s Orange Bowl that the shooting down of civilian aircraft by Fidel Castro’s pilots was ‘not cojones but cowardice.’ By sheer force of personality, she became a key player, especially with regard to the Balkans.” (Herring, chap. 20, p. 932)

John Jacob Astor (1763-1848)

John Jacob Astor (1763-1848)

“Encouraged by Jefferson’s offer of ‘every reasonable [government] patronage,’ the New York merchant John Jacob Astor immediately set out to capture the fur trade by constructing a series of posts from the Missouri River to the Columbia. In 1811, he established a fort at the mouth of the Columbia, laying the first substantial American claim to the Oregon territory. During the War of 1812, Astor loaned a near bankrupt United States $2.5 million in return for promises to defend Astoria it could not keep.” (Herring, chap. 3, p. 114)

James Baker (1930 – )

“After the Gulf War, the [George H.W. Bush] administration acted decisively only in the Middle East. From the outset, Bush and Secretary of State James Baker had made clear their determination to break the long-standing deadlock in Arab-Israeli negotiations. Israel must accept the principle of land for peace as specified in US Resolution 242. It must ‘lay aside, once and for all, the unrealistic vision of a greater Israel,’ Baker boldly informed an American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) gathering in May 1989. The end of the Cold War, the demise of the Soviet Union , and the defeat of Iraq seemed to strengthen the administration’s hand. The Palestinians would no longer have an arms supplier. By easing the threat from Iraq, the United States presumably gained greater leverage with Israel. Working with moderate Palestinians in the West Bank rather than Arafat’s PLO, the administration secured agreement of the major Arab states for a peace conference. Baker jawboned hard-line Israeli premier Yitzhak Shamir into attending.” (Herring, chap. 20, pp. 922-23)

“After the Gulf War, the [George H.W. Bush] administration acted decisively only in the Middle East. From the outset, Bush and Secretary of State James Baker had made clear their determination to break the long-standing deadlock in Arab-Israeli negotiations. Israel must accept the principle of land for peace as specified in US Resolution 242. It must ‘lay aside, once and for all, the unrealistic vision of a greater Israel,’ Baker boldly informed an American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) gathering in May 1989. The end of the Cold War, the demise of the Soviet Union , and the defeat of Iraq seemed to strengthen the administration’s hand. The Palestinians would no longer have an arms supplier. By easing the threat from Iraq, the United States presumably gained greater leverage with Israel. Working with moderate Palestinians in the West Bank rather than Arafat’s PLO, the administration secured agreement of the major Arab states for a peace conference. Baker jawboned hard-line Israeli premier Yitzhak Shamir into attending.” (Herring, chap. 20, pp. 922-23)

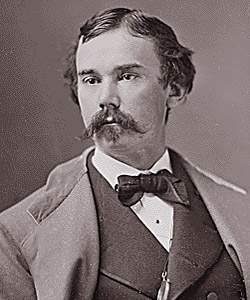

James G. Blaine (1830-1893)

“The pace of U.S. overseas activity quickened from 1889 to 1893 under the aggressive leadership of President Benjamin Harrison and Secretary of State Blaine. Defeated by Cleveland for the presidency in 1884, Blaine declined to run four years later. The Republicans nominated instead the Indiana lawyer, U.S. senator, and grandson of President William Henry Harrison. As a Senate mentor, Blaine had helped convert the Indianian to expansionism. The cold, aloof president and his dynamic, charismatic adviser never formed a close working relationship; their collaboration was often beset with rivalry and tension. But the two pursued an activist, sometimes belligerent foreign policy that jump-started a decade of expansionism, energetically reasserting U.S. leadership on the hemisphere, pushing reciprocity with renewed vigor, escalating a minor crisis with Chile to the point of war, aggressively pursuing naval bases in the Caribbean and Pacific, and even giving the green light to a coup d’etat in Hawaii. Small of stature with a high-pitched voice, ‘Little Ben’ was especially bellicose and on several occasions had to be restrained by the man known as ‘Jingo Jim.'” (Herring, chap. 7, pp. 292-3)

“The pace of U.S. overseas activity quickened from 1889 to 1893 under the aggressive leadership of President Benjamin Harrison and Secretary of State Blaine. Defeated by Cleveland for the presidency in 1884, Blaine declined to run four years later. The Republicans nominated instead the Indiana lawyer, U.S. senator, and grandson of President William Henry Harrison. As a Senate mentor, Blaine had helped convert the Indianian to expansionism. The cold, aloof president and his dynamic, charismatic adviser never formed a close working relationship; their collaboration was often beset with rivalry and tension. But the two pursued an activist, sometimes belligerent foreign policy that jump-started a decade of expansionism, energetically reasserting U.S. leadership on the hemisphere, pushing reciprocity with renewed vigor, escalating a minor crisis with Chile to the point of war, aggressively pursuing naval bases in the Caribbean and Pacific, and even giving the green light to a coup d’etat in Hawaii. Small of stature with a high-pitched voice, ‘Little Ben’ was especially bellicose and on several occasions had to be restrained by the man known as ‘Jingo Jim.'” (Herring, chap. 7, pp. 292-3)

Zbigniew Brzezinski (1928 – 2017)

“A Columbia University professor and prolific writer on international relations, Zbig, as he was known, brought to the position a resume much like Kissinger’s, although he lacked his predecessor’s nimble mind, trademark wit, and ability to charm the media. Born in Poland, the son of a diplomat, he boasted, so the joke went, of being ‘the first Pole in 300 years in a position to really stick it to the Russians.’ His butch haircut in an age of floppy hairstyles and sharp features gave physical evidence of the aggressive posture toward the Kremlin he would relentlessly push. Prickly and arrogant, he scorned [Cyrus] Vance’s ‘gentlemanly approach to the world.’ He advocated ‘architecture’ in foreign policy, by which he meant clarity and certitude , as opposed to Kissinger’s ‘acrobatics.'” (Herring, chap. 18, p. 832)

“A Columbia University professor and prolific writer on international relations, Zbig, as he was known, brought to the position a resume much like Kissinger’s, although he lacked his predecessor’s nimble mind, trademark wit, and ability to charm the media. Born in Poland, the son of a diplomat, he boasted, so the joke went, of being ‘the first Pole in 300 years in a position to really stick it to the Russians.’ His butch haircut in an age of floppy hairstyles and sharp features gave physical evidence of the aggressive posture toward the Kremlin he would relentlessly push. Prickly and arrogant, he scorned [Cyrus] Vance’s ‘gentlemanly approach to the world.’ He advocated ‘architecture’ in foreign policy, by which he meant clarity and certitude , as opposed to Kissinger’s ‘acrobatics.'” (Herring, chap. 18, p. 832)

Pearl Buck (1892-1973)

“Reactions in the United States to the Sino-Japanese War varied. Many Americans still saw Japan as a bulwark against Soviet Russia and even against Chinese revolutionary nationalism. Some Americans valued a flourishing trade with Japan. On the other hand, many increasingly took sides. Missionaries who remained to help the Chinese reported the horrors of Japanese aggression; accounts of the rape of Nanking caused particular outrage. Warning that the United States must not be intimidated by ‘Al Capone nations,’ missionaries pushed for a ‘Christian boycott’ of Japanese goods and stopping the sale of war materials to Japan. Novelist Pearl Buck and Time-Life mogul Henry Luce, both children of missionary parents, complemented their efforts. Millions of Americans read Peal Buck’s novel The Good Earth, first published in 1931, and identified with the Chinese peasants whose story it told. The movie version appeared in 1937. Luce’s increasingly popular high-circulation magazines and March of Time newsreels also presented highly idealized pictures of China and Chiang Kai-shek, a recent convert to Christianity. Over time, such images swayed U.S. opinion against Japan and toward China. Whatever their sympathies, Americans in late 1937 staunchly opposed going to war.” (Herring, chap. 12, p. 511)

“Reactions in the United States to the Sino-Japanese War varied. Many Americans still saw Japan as a bulwark against Soviet Russia and even against Chinese revolutionary nationalism. Some Americans valued a flourishing trade with Japan. On the other hand, many increasingly took sides. Missionaries who remained to help the Chinese reported the horrors of Japanese aggression; accounts of the rape of Nanking caused particular outrage. Warning that the United States must not be intimidated by ‘Al Capone nations,’ missionaries pushed for a ‘Christian boycott’ of Japanese goods and stopping the sale of war materials to Japan. Novelist Pearl Buck and Time-Life mogul Henry Luce, both children of missionary parents, complemented their efforts. Millions of Americans read Peal Buck’s novel The Good Earth, first published in 1931, and identified with the Chinese peasants whose story it told. The movie version appeared in 1937. Luce’s increasingly popular high-circulation magazines and March of Time newsreels also presented highly idealized pictures of China and Chiang Kai-shek, a recent convert to Christianity. Over time, such images swayed U.S. opinion against Japan and toward China. Whatever their sympathies, Americans in late 1937 staunchly opposed going to war.” (Herring, chap. 12, p. 511)

Henry Clay (1777-1852)

“As secretary of state, [John Quincy] Adams had rebuffed Clay’s proposals to support the Greek and Latin American revolutions –the United States should be the ‘well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all … the champion and vindicator only of her own,’ he proclaimed in an oft-quoted July 4, 1821 oration responding to Clay. But as president he moved in that direction…. Closer to home, Adams and Clay sought to encourage republicanism in Latin America. For years, Clay had ardently championed Latin American independence. As secretary of state, he aspired to commit hemispheric nations to a loose association based on U.S. political and commercial principles. Although skeptical, Adams too came to envision the United States providing leadership to the hemisphere in those ‘very fundamental maxims which we from our cradle at first proclaimed and partially succeeded to introduce into the code of national law.’ The two men feared that the Latin American republics might fall back under European sway in ways that threatened U.S. interests. The best solution seemed to be to reshape them according to North American republican principles and institutions.” (Herring, chap. 4, p. 160)

“As secretary of state, [John Quincy] Adams had rebuffed Clay’s proposals to support the Greek and Latin American revolutions –the United States should be the ‘well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all … the champion and vindicator only of her own,’ he proclaimed in an oft-quoted July 4, 1821 oration responding to Clay. But as president he moved in that direction…. Closer to home, Adams and Clay sought to encourage republicanism in Latin America. For years, Clay had ardently championed Latin American independence. As secretary of state, he aspired to commit hemispheric nations to a loose association based on U.S. political and commercial principles. Although skeptical, Adams too came to envision the United States providing leadership to the hemisphere in those ‘very fundamental maxims which we from our cradle at first proclaimed and partially succeeded to introduce into the code of national law.’ The two men feared that the Latin American republics might fall back under European sway in ways that threatened U.S. interests. The best solution seemed to be to reshape them according to North American republican principles and institutions.” (Herring, chap. 4, p. 160)

Richard Harding Davis (1864-1916)

“The ‘yellow press’ (so named for the ‘Yellow Kid,’ a popular cartoon character that appeared in its newly colored pages) helped make Cuba a cause celebre in the United States. The mass-circulation newspaper came into its own in the 1890s. The New York dailies of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer engaged in a fierce, head-to-head competition with few restraints and fewer scruples about the truth. They eagerly disseminated stories furnished by the junta. Talented artists such as Frederic Remington and writers such as Richard Harding Davis portrayed the revolution as a simple morality play featuring the oppression of freedom-loving Cubans by evil Spaniards. The yellow press undoubtedly contributed to a war spirit, but Americans in areas where it did not circulate also strongly sympathized with Cuba.” (Herring, chap. 8, p. 311)

“The ‘yellow press’ (so named for the ‘Yellow Kid,’ a popular cartoon character that appeared in its newly colored pages) helped make Cuba a cause celebre in the United States. The mass-circulation newspaper came into its own in the 1890s. The New York dailies of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer engaged in a fierce, head-to-head competition with few restraints and fewer scruples about the truth. They eagerly disseminated stories furnished by the junta. Talented artists such as Frederic Remington and writers such as Richard Harding Davis portrayed the revolution as a simple morality play featuring the oppression of freedom-loving Cubans by evil Spaniards. The yellow press undoubtedly contributed to a war spirit, but Americans in areas where it did not circulate also strongly sympathized with Cuba.” (Herring, chap. 8, p. 311)

Charles Dawes (1865-1951)

“The administration named Chicago banker Charles G. Dawes and Owen D. Young, a General Electric executive with close ties to the J.P. Morgan banking firm, to head its group of experts, closely monitored their work, and stepped in on occasion to mediate disputes. It was no easy task. A settlement had to be hard enough on Germany to satisfy Allied and particularly French concerns while soft enough to be acceptable to Berlin. The fast-talking and indefatigable Dawes –an ‘astounding human dynamo,’ once colleague called him– also had close connections to France from his wartime service in Paris and helped bring the French along. Young devised a flexible and ingenious plan, ironically one that would bear Dawes’s name, that became a means not only to solve the intractable reparations problem but also to promote German recovery….Hoover exulted in the ‘disinterested statesmanship’ carried out by private American citizens and labeled the Dawes Plan a ‘peace mission without parallel in international history.'” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 459)

“The administration named Chicago banker Charles G. Dawes and Owen D. Young, a General Electric executive with close ties to the J.P. Morgan banking firm, to head its group of experts, closely monitored their work, and stepped in on occasion to mediate disputes. It was no easy task. A settlement had to be hard enough on Germany to satisfy Allied and particularly French concerns while soft enough to be acceptable to Berlin. The fast-talking and indefatigable Dawes –an ‘astounding human dynamo,’ once colleague called him– also had close connections to France from his wartime service in Paris and helped bring the French along. Young devised a flexible and ingenious plan, ironically one that would bear Dawes’s name, that became a means not only to solve the intractable reparations problem but also to promote German recovery….Hoover exulted in the ‘disinterested statesmanship’ carried out by private American citizens and labeled the Dawes Plan a ‘peace mission without parallel in international history.'” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 459)

Silas Deane (1738-1789)

“The committee sounded out Bonvouloir on French willingness to sell war supplies. Encouraged by the response, it sent Connecticut merchant Silas Deane to France to arrange for the purchase of arms and other equipment….From the time he landed in Paris, the energetic but often indiscreet Deane compromised his own mission. He cut deals that benefited the rebel cause –and from which he profited handsomely, provoking later charges of malfeasance and a nasty spat in Congress. He was surrounded by spies, and his employment of the notorious British agent Edward Bancroft produced an intelligence windfall for London. He recruited French officers to serve in the Continental Army and even plotted to replace Washington as commander. He endorsed sabotage operations against British ports, provoking angry protests to France. Even more dangerously, he and irascible colleague Arthur Lee made the French increasingly uneasy about supporting the Americans” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 15, 19).

“The committee sounded out Bonvouloir on French willingness to sell war supplies. Encouraged by the response, it sent Connecticut merchant Silas Deane to France to arrange for the purchase of arms and other equipment….From the time he landed in Paris, the energetic but often indiscreet Deane compromised his own mission. He cut deals that benefited the rebel cause –and from which he profited handsomely, provoking later charges of malfeasance and a nasty spat in Congress. He was surrounded by spies, and his employment of the notorious British agent Edward Bancroft produced an intelligence windfall for London. He recruited French officers to serve in the Continental Army and even plotted to replace Washington as commander. He endorsed sabotage operations against British ports, provoking angry protests to France. Even more dangerously, he and irascible colleague Arthur Lee made the French increasingly uneasy about supporting the Americans” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 15, 19).

William Donovan (1883-1959)

“The Coordinator of Information, precursor to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) –and subsequently the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)– was America’s first independent intelligence agency….Headed by a World War I Medal of Honor winner, the flamboyant Col. William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, the OSS at its peak employed thirteen thousand people, as many as nine thousand overseas. Bearing a distinct Ivy League hue, it brought to Washington scholars such as historians Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Sherman Kent, and even the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse, to analyze the vast amounts of information collected on enemy capabilities and operations. Clandestine operatives such as the legendary Virginia Hall slipped into North Africa and Europe to prepare the way for Allied military operations and carried out black propaganda operations and ‘dirty tricks’ in Axis-occupied areas and enemy territory. OSS agents in various guises worked with partisan and guerrilla groups in the Balkans and East Asia. In Bern, a Secret Intelligence unit headed by Allen Dulles established contact with opponents of Hitler and gathered information about the Nazi regime.” (Herring, chap. 13, pp. 542-3)

“The Coordinator of Information, precursor to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) –and subsequently the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)– was America’s first independent intelligence agency….Headed by a World War I Medal of Honor winner, the flamboyant Col. William ‘Wild Bill’ Donovan, the OSS at its peak employed thirteen thousand people, as many as nine thousand overseas. Bearing a distinct Ivy League hue, it brought to Washington scholars such as historians Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Sherman Kent, and even the Marxist philosopher Herbert Marcuse, to analyze the vast amounts of information collected on enemy capabilities and operations. Clandestine operatives such as the legendary Virginia Hall slipped into North Africa and Europe to prepare the way for Allied military operations and carried out black propaganda operations and ‘dirty tricks’ in Axis-occupied areas and enemy territory. OSS agents in various guises worked with partisan and guerrilla groups in the Balkans and East Asia. In Bern, a Secret Intelligence unit headed by Allen Dulles established contact with opponents of Hitler and gathered information about the Nazi regime.” (Herring, chap. 13, pp. 542-3)

John Foster Dulles (1888-1959)

“John Foster Dulles became the nation’s chief diplomat almost as a matter of inheritance. The grandson and namesake of late nineteenth-century secretary of state John W. Foster and nephew of Wilson’s chief diplomat, Robert Lansing, he carried out his first diplomatic assignment at the age of thirty when he drafted the notorious reparations settlement at the Paris peace conference. As a partner in the powerful New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, he joined the world of corporate wealth and international finance. Like Woodrow Wilson the son of a Presbyterian minister, Dulles applied his intense religiosity to analyzing the tumultuous international politics of the 1930s and ’40s. A great bear of a man, stern and unsmiling, he could appear brusque, even rude –‘the only bull who carried his own China closet with him,’ Winston Churchill once snarled (and indeed Dulles was a collector of rare china). An indefatigable worker, as secretary of state he set a record by traveling more than a half million miles. Once viewed as the dominant force in policymaking in the Eisenhower years, he and the president in fact formed an extraordinarily close partnership based on mutual respect in which the latter was plainly preeminent. Dulles’s strident anti-Communist rhetoric and penchant for ‘brinkmanship’ stamped him as an ideologue and crusader. He often served as a lightning rod for his boss. He was also a cool pragmatist with a sophisticated view of the world and ample tactical skills.” (Herring, chap. 15, p. 657)

“John Foster Dulles became the nation’s chief diplomat almost as a matter of inheritance. The grandson and namesake of late nineteenth-century secretary of state John W. Foster and nephew of Wilson’s chief diplomat, Robert Lansing, he carried out his first diplomatic assignment at the age of thirty when he drafted the notorious reparations settlement at the Paris peace conference. As a partner in the powerful New York law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, he joined the world of corporate wealth and international finance. Like Woodrow Wilson the son of a Presbyterian minister, Dulles applied his intense religiosity to analyzing the tumultuous international politics of the 1930s and ’40s. A great bear of a man, stern and unsmiling, he could appear brusque, even rude –‘the only bull who carried his own China closet with him,’ Winston Churchill once snarled (and indeed Dulles was a collector of rare china). An indefatigable worker, as secretary of state he set a record by traveling more than a half million miles. Once viewed as the dominant force in policymaking in the Eisenhower years, he and the president in fact formed an extraordinarily close partnership based on mutual respect in which the latter was plainly preeminent. Dulles’s strident anti-Communist rhetoric and penchant for ‘brinkmanship’ stamped him as an ideologue and crusader. He often served as a lightning rod for his boss. He was also a cool pragmatist with a sophisticated view of the world and ample tactical skills.” (Herring, chap. 15, p. 657)

Hamilton Fish (1808-1893)

“Like [William] Seward, Grant’s secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, was a New Yorker. In contrast to his flamboyant predecessor, the wealthy and socially prominent Fish was dignified and stodgy. Where Seward had coveted his cabinet post as a stepping-stone to the presidency, Fish dismissed it as one ‘for which I have little taste and less fitness.’ Taste and fitness notwithstanding, he ranks among the nation’s better secretaries of state, in large part because of his settlement of the Alabama claims dispute with Britain. Unimaginative and somewhat rigid in his thinking, he was a person of good judgment and distinguished himself in an administration not noted for integrity or accomplishments of its top officials. He served longer than any other individual who held the post in the nineteenth century.” (Herring, chap. 6, p. 258)

“Like [William] Seward, Grant’s secretary of state, Hamilton Fish, was a New Yorker. In contrast to his flamboyant predecessor, the wealthy and socially prominent Fish was dignified and stodgy. Where Seward had coveted his cabinet post as a stepping-stone to the presidency, Fish dismissed it as one ‘for which I have little taste and less fitness.’ Taste and fitness notwithstanding, he ranks among the nation’s better secretaries of state, in large part because of his settlement of the Alabama claims dispute with Britain. Unimaginative and somewhat rigid in his thinking, he was a person of good judgment and distinguished himself in an administration not noted for integrity or accomplishments of its top officials. He served longer than any other individual who held the post in the nineteenth century.” (Herring, chap. 6, p. 258)

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790)

“Franklin’s mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America’s revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue. (Herring, chap 1, p. 19)

“Franklin’s mission to Paris is one of the most extraordinary episodes in the history of American diplomacy, important, if not indeed decisive, to the outcome of the Revolution. The eminent scientist, journalist, politician, and homespun philosopher was already an international celebrity when he landed in France. Establishing himself in a comfortable house with a well-stocked wine cellar in a suburb Paris, he made himself the toast of the city. A steady flow of visitors requested audiences and favors such as commissions in the American army. Through clever packaging, he presented himself to French society as the very embodiment of America’s revolution, a model of republican simplicity and virtue. (Herring, chap 1, p. 19)

Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804)

“Both [Thomas Jefferson and Hamilton] shared the long-range goal of a strong nation, independent of the great powers of Europe, but they approached it from quite different perspectives, advocating coherent systems of political economy in which foreign and domestic policies were inextricably linked with sharply conflicting visions of what America should be. Hamilton was the more patient. He preferred to build national power and then ‘dictate the terms of the connection between the old world and the new.’ Modeling his system on that of England, he sought to establish a strong government and stable economy that would attract investment capital and promote manufactures. Though expansion of the home market he hoped in time to get around Britain’s commercial restrictions and even challenge its supremacy, but for the moment he would acquiesce. His economic program hinged on revenues from trade with England, and he opposed anything that threatened it. Horrified at the excesses of the French Revolution, he condemned Jefferson’s ‘womanish attachment’ to France and increasingly saw England as a bastion of stable governing principles. More accurate than Jefferson and Madison in his assessment of American weakness and therefore more willing to make concessions to Britain, he pursued peace with a zeal that compromised American pride and honor and engaged in machinations that could have undermined American interests. His lust for power could be both reckless and destructive.” (Herring, chap. 2, p. 65)

“Both [Thomas Jefferson and Hamilton] shared the long-range goal of a strong nation, independent of the great powers of Europe, but they approached it from quite different perspectives, advocating coherent systems of political economy in which foreign and domestic policies were inextricably linked with sharply conflicting visions of what America should be. Hamilton was the more patient. He preferred to build national power and then ‘dictate the terms of the connection between the old world and the new.’ Modeling his system on that of England, he sought to establish a strong government and stable economy that would attract investment capital and promote manufactures. Though expansion of the home market he hoped in time to get around Britain’s commercial restrictions and even challenge its supremacy, but for the moment he would acquiesce. His economic program hinged on revenues from trade with England, and he opposed anything that threatened it. Horrified at the excesses of the French Revolution, he condemned Jefferson’s ‘womanish attachment’ to France and increasingly saw England as a bastion of stable governing principles. More accurate than Jefferson and Madison in his assessment of American weakness and therefore more willing to make concessions to Britain, he pursued peace with a zeal that compromised American pride and honor and engaged in machinations that could have undermined American interests. His lust for power could be both reckless and destructive.” (Herring, chap. 2, p. 65)

Townsend Harris (1804-1878)

“It remained for Townsend Harris, a diplomat of undistinguished credentials with no force at his disposal, to establish the foundation for Japan’s relations with the West for the remainder of the century. Arriving in 1856 as the first U.S. consul, he was shunted to the small and inaccessible village of Shimoda by a government that would have preferred he stay at home. He was forced to share a run-down temple with rats, bats, and enormous spiders. Sometimes going months without word from Washington, Harris rightly considered himself the ‘most isolated American official in the world.’ Frustrated by Japanese obstructionism, he also came to admire the Japanese people and appreciate their culture, perhaps through the influence of a mistress, assigned him by the government, who may have been the inspiration for Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly. Confident that with patience the West could elevate Japan to ‘our standards of civilization,’ Harris stubbornly persisted, repeatedly warning his hosts that it would be better to deal peaceably with the United States than risk China’s fate at the hands of the Europeans. Eventually, he prevailed.” (Herring, chap. 5, p. 213)

“It remained for Townsend Harris, a diplomat of undistinguished credentials with no force at his disposal, to establish the foundation for Japan’s relations with the West for the remainder of the century. Arriving in 1856 as the first U.S. consul, he was shunted to the small and inaccessible village of Shimoda by a government that would have preferred he stay at home. He was forced to share a run-down temple with rats, bats, and enormous spiders. Sometimes going months without word from Washington, Harris rightly considered himself the ‘most isolated American official in the world.’ Frustrated by Japanese obstructionism, he also came to admire the Japanese people and appreciate their culture, perhaps through the influence of a mistress, assigned him by the government, who may have been the inspiration for Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly. Confident that with patience the West could elevate Japan to ‘our standards of civilization,’ Harris stubbornly persisted, repeatedly warning his hosts that it would be better to deal peaceably with the United States than risk China’s fate at the hands of the Europeans. Eventually, he prevailed.” (Herring, chap. 5, p. 213)

John Hay (1838-1905)

“Once the Spanish crisis had ended, the McKinley administration also took a stand in defense of U.S. trade in China. The task fell to newly appointed Secretary of State John Hay. At one time Lincoln’s private secretary, the dapper, witty, and multitalented Hay had worked in business and journalism and was also an accomplished poet, novelist, and biographer. He had served in diplomatic posts in Vienna, Paris, Madrid, and London before returning to Washington. Independently wealthy, urbane, and extraordinarily well connected, the Indianan was a shrewd politician. Like many Republicans, he had once opposed expansion, but he gave way in the 1890s to what he called a ‘cosmic tendency.’ Pressured by China hands like W.W. Rockhill, Hay concluded that a statement of the U.S. position on freedom of trade in China would appease American businessmen and possibly earn some goodwill among the Chinese that might benefit the United States commercially. It would convince expansionists the United States was prepared to live up to its responsibilities as an Asian power.” (Herring, chap. 8, p. 331)

“Once the Spanish crisis had ended, the McKinley administration also took a stand in defense of U.S. trade in China. The task fell to newly appointed Secretary of State John Hay. At one time Lincoln’s private secretary, the dapper, witty, and multitalented Hay had worked in business and journalism and was also an accomplished poet, novelist, and biographer. He had served in diplomatic posts in Vienna, Paris, Madrid, and London before returning to Washington. Independently wealthy, urbane, and extraordinarily well connected, the Indianan was a shrewd politician. Like many Republicans, he had once opposed expansion, but he gave way in the 1890s to what he called a ‘cosmic tendency.’ Pressured by China hands like W.W. Rockhill, Hay concluded that a statement of the U.S. position on freedom of trade in China would appease American businessmen and possibly earn some goodwill among the Chinese that might benefit the United States commercially. It would convince expansionists the United States was prepared to live up to its responsibilities as an Asian power.” (Herring, chap. 8, p. 331)

Edward House (1858-1938)

“[Woodrow] Wilson’s views were influenced by Col. Edward M. House (the title was honorific), a wealthy Texas politico who without official position remained his alter ego and closest adviser until the last years of his presidency. Small of stature, quiet and self-effacing, House was a shrewd judge of people and a skilled behind-the-scenes operator. His aspirations were revealed in his anonymously published novel, Philip Dru: Administrator, the tale of a Kentuckian and West Point graduate who after corralling the special interests at home launched a crusade with Britain against Germany and Japan for disarmament and the removal of trade barriers.” (Herring, chap. 10, p. 380)

“[Woodrow] Wilson’s views were influenced by Col. Edward M. House (the title was honorific), a wealthy Texas politico who without official position remained his alter ego and closest adviser until the last years of his presidency. Small of stature, quiet and self-effacing, House was a shrewd judge of people and a skilled behind-the-scenes operator. His aspirations were revealed in his anonymously published novel, Philip Dru: Administrator, the tale of a Kentuckian and West Point graduate who after corralling the special interests at home launched a crusade with Britain against Germany and Japan for disarmament and the removal of trade barriers.” (Herring, chap. 10, p. 380)

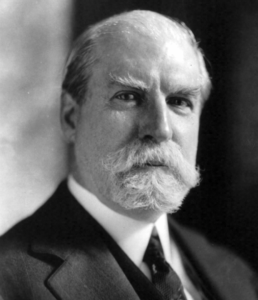

Charles Evans Hughes (1862-1948)

“During the 1920s, the secretaries of state resumed the preeminent role in policymaking they had played before McKinley and Roosevelt. The New York lawyer and unsuccessful presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes was one of the ablest ever to hold the post. An indefatigable worker, utterly devoted to the job, he filled the sizeable void left by Harding and Coolidge and was perhaps the last secretary to personally manage U.S. foreign policy. Hughes ably presided over a department with a budget of $2 million and a staff of six hundred people. He won the loyalty of his aides with his dedication and warm, outgoing personality. Blessed with a brilliant mind, he was also politically astute.” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 442)

“During the 1920s, the secretaries of state resumed the preeminent role in policymaking they had played before McKinley and Roosevelt. The New York lawyer and unsuccessful presidential candidate Charles Evans Hughes was one of the ablest ever to hold the post. An indefatigable worker, utterly devoted to the job, he filled the sizeable void left by Harding and Coolidge and was perhaps the last secretary to personally manage U.S. foreign policy. Hughes ably presided over a department with a budget of $2 million and a staff of six hundred people. He won the loyalty of his aides with his dedication and warm, outgoing personality. Blessed with a brilliant mind, he was also politically astute.” (Herring, chap. 11, p. 442)

John Jay (1745-1829)

“One area of progress [under the Articles of Confederation] was in the administration of foreign affairs. [Robert] Livingston had repeatedly complained of inadequate authority and congressional interference. He resigned before the peace treaty was ratified. Congress responded by strengthening the position of the secretary of foreign affairs. John Jay assumed the office in December 1784 and held it until a new government took power in 1789, providing needed continuity. An able administrator, he insisted that his office have full responsibility for the nation’s diplomacy. Remarkably, he also conditioned his acceptance on Congress settling in New York. Assisted by four clerks and several part-time translators, he worked out of two rooms in a tavern near Congress’s meeting place. He did not achieve his major foreign policy goals, but he managed his department efficiently. Interestingly, a secret act of Congress authorized him to open and examine any letters going through the post office that might contain information endangering the ‘safety or interest of the United States.’ He appears not to have used this authority.” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 35-6)

“One area of progress [under the Articles of Confederation] was in the administration of foreign affairs. [Robert] Livingston had repeatedly complained of inadequate authority and congressional interference. He resigned before the peace treaty was ratified. Congress responded by strengthening the position of the secretary of foreign affairs. John Jay assumed the office in December 1784 and held it until a new government took power in 1789, providing needed continuity. An able administrator, he insisted that his office have full responsibility for the nation’s diplomacy. Remarkably, he also conditioned his acceptance on Congress settling in New York. Assisted by four clerks and several part-time translators, he worked out of two rooms in a tavern near Congress’s meeting place. He did not achieve his major foreign policy goals, but he managed his department efficiently. Interestingly, a secret act of Congress authorized him to open and examine any letters going through the post office that might contain information endangering the ‘safety or interest of the United States.’ He appears not to have used this authority.” (Herring, chap. 1, pp. 35-6)

George Kennan (1904-2005)

“The namesake of a distant relative who in the late nineteenth century had documented for enthralled US. audiences the horrors of the Siberian exile system, the younger [George] Kennan was one of a handful of men trained after World War I as experts on Bolshevik Russia. Conservative in his tastes and politics and scholarly in demeanor, he developed a deep admiration for traditional Russian literature and culture and, from service in the Moscow embassy after 1933, an even deeper antipathy for the Soviet state. Frustrated during the war when the Roosevelt administration ignored his cautionary recommendations, he eagerly responded when Truman’s State Department requested his views. ‘They had asked for it,’ he later wrote. ‘Now, by God, they would get it.’ In highly alarmist tones, he delivered over the wires [in early 1946] a lecture on Soviet behavior that decisively influenced the origins and nature of the Cold War.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 604)

“The namesake of a distant relative who in the late nineteenth century had documented for enthralled US. audiences the horrors of the Siberian exile system, the younger [George] Kennan was one of a handful of men trained after World War I as experts on Bolshevik Russia. Conservative in his tastes and politics and scholarly in demeanor, he developed a deep admiration for traditional Russian literature and culture and, from service in the Moscow embassy after 1933, an even deeper antipathy for the Soviet state. Frustrated during the war when the Roosevelt administration ignored his cautionary recommendations, he eagerly responded when Truman’s State Department requested his views. ‘They had asked for it,’ he later wrote. ‘Now, by God, they would get it.’ In highly alarmist tones, he delivered over the wires [in early 1946] a lecture on Soviet behavior that decisively influenced the origins and nature of the Cold War.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 604)

Henry Kissinger (1923 –

“The ‘team’ that would devise new policies for a new era comprised an unlikely duo at best. As part of the Jewish diaspora of the 1930s, Henry Alfred Kissinger fled Nazi Germany as a youth and settled in New York City. After serving in the army, he earned a B.A. and Ph.D. in political science at Harvard, writing a dissertation on Castlereagh and Metternich, the architects of post-Napoleonic world order. As a faculty member at Harvard, he cultivated the international foreign policy elite, and his books on important issues brought him to the attention of establishment figures. He advised moderate Republican Nelson Rockefeller on foreign policy. As a consultant for the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, he participated in several Vietnam peace initiatives. During the 1968 campaign, he shamelessly played various sides agains the middle. His owlish professorial appearance and dry, self-effacing wit only partially obscured an enormous ego and a burning ambition to shape policies rather than write about them. His thick German accent and slow speech seemed to give authority to his pronouncements.” (Herring, chap. 17, p. 763)

“The ‘team’ that would devise new policies for a new era comprised an unlikely duo at best. As part of the Jewish diaspora of the 1930s, Henry Alfred Kissinger fled Nazi Germany as a youth and settled in New York City. After serving in the army, he earned a B.A. and Ph.D. in political science at Harvard, writing a dissertation on Castlereagh and Metternich, the architects of post-Napoleonic world order. As a faculty member at Harvard, he cultivated the international foreign policy elite, and his books on important issues brought him to the attention of establishment figures. He advised moderate Republican Nelson Rockefeller on foreign policy. As a consultant for the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, he participated in several Vietnam peace initiatives. During the 1968 campaign, he shamelessly played various sides agains the middle. His owlish professorial appearance and dry, self-effacing wit only partially obscured an enormous ego and a burning ambition to shape policies rather than write about them. His thick German accent and slow speech seemed to give authority to his pronouncements.” (Herring, chap. 17, p. 763)

Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974)

“In July [1940], Yale University students and midwestern businessmen formed the America First Committee. As the name suggests, America Firsters ardently opposed intervention –and aid to Britain, which, they argued, would inevitably lead to intervention. They saw the war not as a great ideological conflict but as another round in the endless struggle among Europeans for power and empire. The United States, they insisted, had no stake in that conflict. Some like aviator hero Charles Lindbergh preached accommodation with Hitler. Others minimized the German threat and advocated defense of the Western Hemisphere. America First was an unwieldy coalition of strange bedfellows, businessmen, old progressives and leftists, and some strongly anti-Jewish groups. Many blamed Roosevelt’s interventionist policies on a personal lust for power. These various groups created local and regional offices, organized rallies, sent out mailings, and propagandized Congress.” (Herring, chap. 12, p. 522)

“In July [1940], Yale University students and midwestern businessmen formed the America First Committee. As the name suggests, America Firsters ardently opposed intervention –and aid to Britain, which, they argued, would inevitably lead to intervention. They saw the war not as a great ideological conflict but as another round in the endless struggle among Europeans for power and empire. The United States, they insisted, had no stake in that conflict. Some like aviator hero Charles Lindbergh preached accommodation with Hitler. Others minimized the German threat and advocated defense of the Western Hemisphere. America First was an unwieldy coalition of strange bedfellows, businessmen, old progressives and leftists, and some strongly anti-Jewish groups. Many blamed Roosevelt’s interventionist policies on a personal lust for power. These various groups created local and regional offices, organized rallies, sent out mailings, and propagandized Congress.” (Herring, chap. 12, p. 522)

Walter Lippmann (1889-1974)

“Responded to [Henry] Luce’s 1941 call for an ‘American Century,’ Vice President [Henry] Wallace proclaimed the ‘century of the common man’ and advocated a ‘people’s revolution’ –a global New Deal– to ensure that all peoples had ‘the privilege of drinking a quart of milk every day.’ Sumner Welles and contract bridge guru Ely Culbertson advocated an international police force; others proposed a world federation. Wendell Willkie’s stirring account of his global tour, One World, stressed that the shrinkage of distances had brought peoples together and made peace indivisible. It enjoyed the highest sales of any book published in the United States to this time. Alarmed by the rampant idealism of Wallace and Willkie, Yale University political geographer Nicholas Spykman urged a realpolitik approach to the postwar world. Journalist and onetime Wilsonian Walter Lippmann’s 1943 book, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic, echoed Spykman in calling for foreign policy based on the balance of power. An instant best seller, it was excerpted in the Reader’s Digest and, most remarkably, appeared in a cartoon version in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Polls taken in 1942-43 indicated broad popular support for U.S. participation in an international organization. Congress jumped out ahead of the White House in late 1943 by approving separate resolutions to that effect.” (Herring, chap. 13, p. 581)

“Responded to [Henry] Luce’s 1941 call for an ‘American Century,’ Vice President [Henry] Wallace proclaimed the ‘century of the common man’ and advocated a ‘people’s revolution’ –a global New Deal– to ensure that all peoples had ‘the privilege of drinking a quart of milk every day.’ Sumner Welles and contract bridge guru Ely Culbertson advocated an international police force; others proposed a world federation. Wendell Willkie’s stirring account of his global tour, One World, stressed that the shrinkage of distances had brought peoples together and made peace indivisible. It enjoyed the highest sales of any book published in the United States to this time. Alarmed by the rampant idealism of Wallace and Willkie, Yale University political geographer Nicholas Spykman urged a realpolitik approach to the postwar world. Journalist and onetime Wilsonian Walter Lippmann’s 1943 book, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic, echoed Spykman in calling for foreign policy based on the balance of power. An instant best seller, it was excerpted in the Reader’s Digest and, most remarkably, appeared in a cartoon version in the Ladies’ Home Journal. Polls taken in 1942-43 indicated broad popular support for U.S. participation in an international organization. Congress jumped out ahead of the White House in late 1943 by approving separate resolutions to that effect.” (Herring, chap. 13, p. 581)

Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924)

“For the next eight months, the nation engaged in yet another great debate over its role in the world….The struggle contained many interlocking elements. Wilson had stretched executive powers before and during the war. At one level, it represented a clash between competing branches of government. It was also an intensely personal feud between two men who despised each other. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge had disliked Wilson from the start. By 1915, he called the president, except for James Buchanan, ‘the most dangerous man that ever sat in the White House’ and confided in Roosevelt that he ‘never expected to hate anyone in politics with the hatred I feel towards Wilson.’ Lodge set out to defeat and humiliate his archenemy over the League [of Nations] issue. The president was determined not to let his foe thwart his great cause.” (Herring, chap. 10, p. 427)

“For the next eight months, the nation engaged in yet another great debate over its role in the world….The struggle contained many interlocking elements. Wilson had stretched executive powers before and during the war. At one level, it represented a clash between competing branches of government. It was also an intensely personal feud between two men who despised each other. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge had disliked Wilson from the start. By 1915, he called the president, except for James Buchanan, ‘the most dangerous man that ever sat in the White House’ and confided in Roosevelt that he ‘never expected to hate anyone in politics with the hatred I feel towards Wilson.’ Lodge set out to defeat and humiliate his archenemy over the League [of Nations] issue. The president was determined not to let his foe thwart his great cause.” (Herring, chap. 10, p. 427)

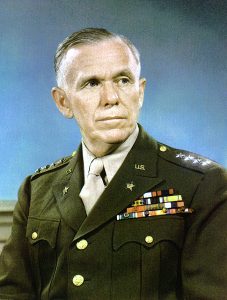

George C. Marshall (1880-1959)

“The independent and unpredictable [James] Byrnes resigned in late 1946, and Truman named the illustrious George C. Marshall to succeed him. The president had enormous regard for the general –‘What I like about Marshall is he’s a man,’ he once affirmed, the highest praise one gentleman of that era could lavish upon another. A person of vast experience, good judgment, and towering prestige, Marshall could shield the State Department from partisan attack and could be counted upon to work closely with the president, areas where Byrnes had conspicuously failed. Indeed, under Marshall’s firm leadership and orderly administrative style, the State Department enjoyed a rare period of preeminence in the making of U.S. foreign policy.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 612)

“The independent and unpredictable [James] Byrnes resigned in late 1946, and Truman named the illustrious George C. Marshall to succeed him. The president had enormous regard for the general –‘What I like about Marshall is he’s a man,’ he once affirmed, the highest praise one gentleman of that era could lavish upon another. A person of vast experience, good judgment, and towering prestige, Marshall could shield the State Department from partisan attack and could be counted upon to work closely with the president, areas where Byrnes had conspicuously failed. Indeed, under Marshall’s firm leadership and orderly administrative style, the State Department enjoyed a rare period of preeminence in the making of U.S. foreign policy.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 612)

George Mathews (1739-1812)

“The [Madison] administration’s actions in East Florida in 1812 represent an embarrassing episode in early national history, a failed attempt to take by force territory to which the United States had little claim. Fearing the collapse of Spanish rule, Madison in 1810 dispatched Georgia adventurer George Mathews to inform the residents of East Florida that if they were to separate from Spain they would be welcomed into the United States. The following year, he secured from Congress authorization to use force to prevent a foreign takeover of East Florida, instructing Mathews in such an eventuality to occupy the province or negotiate with the locals. Mathews subsequently sought authority to foment revolution there. The administration’s non-response was interpreted by him –and has been seen by some historians– as tantamount to silent complicity in the scheme. Others persuasively argue that this was standard operating procedure and did not imply consent. Whatever the case, the overzealous Mathews organized a group of local ‘Patriots’ who seized Amelia Island off the Georgia coast and laid siege to St. Augustine. Complaining that Mathews’s ‘extravagance’ had put the administration in ‘the most distressing dilemma,’ Madison disavowed his reckless agent. On the verge of war with Britain, however, and more than ever concerned about the threat to East Florida, he authorized the Patriots to hold on to territory they had taken. Furious with his abandonment, Mathews started home to expose the administration’s complicity. In a rare bit of good luck during his embattled presidency, Madison was spared further embarrassment when Mathews died en route.” (Herring, chap. 3, pp. 111-2)

“The [Madison] administration’s actions in East Florida in 1812 represent an embarrassing episode in early national history, a failed attempt to take by force territory to which the United States had little claim. Fearing the collapse of Spanish rule, Madison in 1810 dispatched Georgia adventurer George Mathews to inform the residents of East Florida that if they were to separate from Spain they would be welcomed into the United States. The following year, he secured from Congress authorization to use force to prevent a foreign takeover of East Florida, instructing Mathews in such an eventuality to occupy the province or negotiate with the locals. Mathews subsequently sought authority to foment revolution there. The administration’s non-response was interpreted by him –and has been seen by some historians– as tantamount to silent complicity in the scheme. Others persuasively argue that this was standard operating procedure and did not imply consent. Whatever the case, the overzealous Mathews organized a group of local ‘Patriots’ who seized Amelia Island off the Georgia coast and laid siege to St. Augustine. Complaining that Mathews’s ‘extravagance’ had put the administration in ‘the most distressing dilemma,’ Madison disavowed his reckless agent. On the verge of war with Britain, however, and more than ever concerned about the threat to East Florida, he authorized the Patriots to hold on to territory they had taken. Furious with his abandonment, Mathews started home to expose the administration’s complicity. In a rare bit of good luck during his embattled presidency, Madison was spared further embarrassment when Mathews died en route.” (Herring, chap. 3, pp. 111-2)

Joseph McCarthy (1908-1957)

“With the postwar Red Scare already under way, in February 1950, a heretofore obscure Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, in a major speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, claimed to have the names of some 206 Communists working in the State Department, accelerating the witch hunt that would bear his name. Stunned from their complacency, a people who through much of their history had enjoyed relatively cost-free security reacted with panic. A Cold War culture of near hysterical fear, paranoiac suspiciousness, and stifling conformity began to take shape. Militant anticommunism increasingly poisoned the political atmosphere at home and made negotiations with the Soviet Union unthinkable.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 637)

“With the postwar Red Scare already under way, in February 1950, a heretofore obscure Republican senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, in a major speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, claimed to have the names of some 206 Communists working in the State Department, accelerating the witch hunt that would bear his name. Stunned from their complacency, a people who through much of their history had enjoyed relatively cost-free security reacted with panic. A Cold War culture of near hysterical fear, paranoiac suspiciousness, and stifling conformity began to take shape. Militant anticommunism increasingly poisoned the political atmosphere at home and made negotiations with the Soviet Union unthinkable.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 637)

Robert McNamara (1916-2009)

“The [Vietnam] war’s mounting costs were more important than the anti-war movement in generating public concern. Growing casualties, indications that more troops might be required, and LBJ’s belated request for a tax increase combined in late 1967 to produce unmistakable signs of war-weariness. Polls showed a sharp decline in support for the war and the president’s handling of it. The press increasingly questioned U.S. goals and methods. Members of Congress from both parties began to challenge LBJ’s policies. Doubts even arose among his inner circle. The secretary of defense had been so closely identified with Vietnam that it had once been called ‘McNamara’s War.” In 1967, a tormented McNamara unsuccessfully urged the president to stop the bombing of North Vietnam, put a ceiling on U.S. ground troops, scale back war aims, and seek a negotiated settlement. By the end of the year, for many observers, the war become the most visible symbol of a malaise that afflicted American society.” (Herring, chap. 16, p. 741)

“The [Vietnam] war’s mounting costs were more important than the anti-war movement in generating public concern. Growing casualties, indications that more troops might be required, and LBJ’s belated request for a tax increase combined in late 1967 to produce unmistakable signs of war-weariness. Polls showed a sharp decline in support for the war and the president’s handling of it. The press increasingly questioned U.S. goals and methods. Members of Congress from both parties began to challenge LBJ’s policies. Doubts even arose among his inner circle. The secretary of defense had been so closely identified with Vietnam that it had once been called ‘McNamara’s War.” In 1967, a tormented McNamara unsuccessfully urged the president to stop the bombing of North Vietnam, put a ceiling on U.S. ground troops, scale back war aims, and seek a negotiated settlement. By the end of the year, for many observers, the war become the most visible symbol of a malaise that afflicted American society.” (Herring, chap. 16, p. 741)

Paul Nitze (1907-2004)

“NSC-68 was drafted by [Paul] Nitze, who had replaced Kennan as head of the Policy Planning Staff. A Wall Street investment banker, as intense in personality as his mentor James Forrestal, Nitze exceeded Acheson in his gloomy worldview. His study set forth an urgent statement of the national security ideology. It proclaimed the necessity of defending freedom across the world to save it at home. Written in the starkest black-and-white terms, it took a worst case view of Soviet capabilities and intentions. “Animated by a new fanatical faith,” it warned, the USSR was seeking to “impose its absolute authority on the rest of the world.” Soviet expansion had reached a point beyond which it must not be permitted to go.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 638)

“NSC-68 was drafted by [Paul] Nitze, who had replaced Kennan as head of the Policy Planning Staff. A Wall Street investment banker, as intense in personality as his mentor James Forrestal, Nitze exceeded Acheson in his gloomy worldview. His study set forth an urgent statement of the national security ideology. It proclaimed the necessity of defending freedom across the world to save it at home. Written in the starkest black-and-white terms, it took a worst case view of Soviet capabilities and intentions. “Animated by a new fanatical faith,” it warned, the USSR was seeking to “impose its absolute authority on the rest of the world.” Soviet expansion had reached a point beyond which it must not be permitted to go.” (Herring, chap. 14, p. 638)

Matthew Perry (1794-1858)

“The United States took the lead in opening Japan. Encouraged by Britain’s success in China and viewing Japan as a vital coaling station en route to the Celestial Kingdom, the last link in Webster’s ‘great chain,’ [President Millard] Fillmore in 1852 named Cmdre. Matthew Perry to head a mission to Japan. Regarding the Japanese as a ‘weak and semi-barbarous people,’ Perry decided to deal forcibly with them. In July 1853, he steamed defiantly into Edo (later Tokyo) Bay with a fleet of four very large, black-hulled ships, sixty-one guns, and a crew of nearly one thousand men. He maneuvered his ships closer to the city than any foreigner had previously gone…. Perry came back in March 1854 with a larger fleet, threatening this time that if Japan did not treat with him it might suffer the fate of Mexico. Instructed by the State Department to ‘do everything to impress’ the Japanese ‘with a just sense of the power and greatness’ of the United States, he brought with him large quantities of champagne and vintage Kentucky bourbon to grease the wheels of diplomacy, a pair of Sam Colt’s six-shooters, and a history of the Mexican War to validate its military superiority. He employed Chinese coolies and African Americans in his entourage in ways that highlighted the power of whites over peoples of color. He used uniforms, pageants, and music –even a blackface minstrel show– as manifestations of Western cultural supremacy. Perry’s reluctant hosts most likely negotiated in spite of rather than because of his forceful demeanor and cultural symbols.” (Herring, chap. 5, pp. 212-3)

“The United States took the lead in opening Japan. Encouraged by Britain’s success in China and viewing Japan as a vital coaling station en route to the Celestial Kingdom, the last link in Webster’s ‘great chain,’ [President Millard] Fillmore in 1852 named Cmdre. Matthew Perry to head a mission to Japan. Regarding the Japanese as a ‘weak and semi-barbarous people,’ Perry decided to deal forcibly with them. In July 1853, he steamed defiantly into Edo (later Tokyo) Bay with a fleet of four very large, black-hulled ships, sixty-one guns, and a crew of nearly one thousand men. He maneuvered his ships closer to the city than any foreigner had previously gone…. Perry came back in March 1854 with a larger fleet, threatening this time that if Japan did not treat with him it might suffer the fate of Mexico. Instructed by the State Department to ‘do everything to impress’ the Japanese ‘with a just sense of the power and greatness’ of the United States, he brought with him large quantities of champagne and vintage Kentucky bourbon to grease the wheels of diplomacy, a pair of Sam Colt’s six-shooters, and a history of the Mexican War to validate its military superiority. He employed Chinese coolies and African Americans in his entourage in ways that highlighted the power of whites over peoples of color. He used uniforms, pageants, and music –even a blackface minstrel show– as manifestations of Western cultural supremacy. Perry’s reluctant hosts most likely negotiated in spite of rather than because of his forceful demeanor and cultural symbols.” (Herring, chap. 5, pp. 212-3)

Thomas Paine (1737-1809)

“Only thirty-seven years old when he arrived in the United States in 1774, Paine had been a corset maker and minor British government functionary. His best-selling pamphlet Common Sense made an impassioned appeal for independence. It was ‘absurd,’ he insisted, for a ‘continent to be perpetually governed by an island.’ A declaration of independence would gain for America assistance from England’s enemies, France and Spain. It would secure for an independent America peace and prosperity….Paine’s call for independence makes clear the centrality of foreign policy to the birth of the American republic” (Herring, chap. 1, p. 11).

“Only thirty-seven years old when he arrived in the United States in 1774, Paine had been a corset maker and minor British government functionary. His best-selling pamphlet Common Sense made an impassioned appeal for independence. It was ‘absurd,’ he insisted, for a ‘continent to be perpetually governed by an island.’ A declaration of independence would gain for America assistance from England’s enemies, France and Spain. It would secure for an independent America peace and prosperity….Paine’s call for independence makes clear the centrality of foreign policy to the birth of the American republic” (Herring, chap. 1, p. 11).

William Phillips (1878-1968)

“Roosevelt responded [to the imprisonment of Mahatma Gandhi] in 1943 by sending career diplomat William Phillips to India as his personal representative, his furthest and final intrusion into an intractable issue. An Anglophile who looked down on ‘lesser’ peoples, Phillips typified that group of upper-class professional diplomats who manned the State Department. Viewing him as ‘the best type of American gentleman,’ some British officials expected him to sympathize with their position. Once in India, however, he traveled widely and spoke to Indians as well as Britons. He found the British stubbornly uncompromising, the Indians divided on many issues but united in their demand for independence. Seeing firsthand the rising power of Indian nationalism, he pressed the British to make concessions. They rebuffed his interference and even forbade him to see Gandhi, then engaged in a much publicized hunger strike. Phillips eventually left India in frustration, and his generally unsuccessful mission typifies Roosevelt’s approach to this difficult issue. The president refused to challenge Churchill directly and thereby threaten the alliance. On the other hand, he used Phillips to keep the colonial issue alive and pressure the British. Phillips’s presence in India and his growing support for the cause helped regain the trust of Indians and permitted the United States to retain a nominal commitment to the ideal of self-determination.” (Herring, chap. 13, p. 572)

“Roosevelt responded [to the imprisonment of Mahatma Gandhi] in 1943 by sending career diplomat William Phillips to India as his personal representative, his furthest and final intrusion into an intractable issue. An Anglophile who looked down on ‘lesser’ peoples, Phillips typified that group of upper-class professional diplomats who manned the State Department. Viewing him as ‘the best type of American gentleman,’ some British officials expected him to sympathize with their position. Once in India, however, he traveled widely and spoke to Indians as well as Britons. He found the British stubbornly uncompromising, the Indians divided on many issues but united in their demand for independence. Seeing firsthand the rising power of Indian nationalism, he pressed the British to make concessions. They rebuffed his interference and even forbade him to see Gandhi, then engaged in a much publicized hunger strike. Phillips eventually left India in frustration, and his generally unsuccessful mission typifies Roosevelt’s approach to this difficult issue. The president refused to challenge Churchill directly and thereby threaten the alliance. On the other hand, he used Phillips to keep the colonial issue alive and pressure the British. Phillips’s presence in India and his growing support for the cause helped regain the trust of Indians and permitted the United States to retain a nominal commitment to the ideal of self-determination.” (Herring, chap. 13, p. 572)

Colin Powell (1937- )

“The United States had stuck ‘its hand into a thousand-year-old hornet’s nest [in Lebanon] with the expectation that our mere presence might pacify the hornets,’ Army Col. Colin Powell, a top military advisor to [Secretary of Defense Caspar] Weinberger, later recalled. Powell and his boss immediately set out to prevent such deployments in the future. Over the next year, the two of them crafted a long list of conditions under which U.S. forces should be deployed. What came to be called the Weinberger or Powell Doctrine was an immediate response to the debacle in Lebanon and also to the secretary of defense’s nasty, ongoing feud with [Secretary of State George] Shultz over the commitment of military forces abroad. Weinberger later conceded that it also reflected the ‘terrible mistake’ of sending forces to Vietnam without ensuring popular support and providing them the means to win. Made public in late 1984, the ‘doctrine’ provided that U.S. troops must be committed only as a last resort and if it was in the national interest. Objectives must be clearly defined and attainable. Public support must be assured, and the means provided to ensure victory. The doctrine provoked a bloody fight within the Reagan adminstration –Shultz labeled it the ‘Vietnam Syndrome in spades.’ It was never given official sanction. But top military officers staunchly supported it, and as Joint Chiefs chairman in the 1990s Powell would fight vigorously for the application of what had become a doctrine bearing his name.” (Herring, chap.19, p. 875)

“The United States had stuck ‘its hand into a thousand-year-old hornet’s nest [in Lebanon] with the expectation that our mere presence might pacify the hornets,’ Army Col. Colin Powell, a top military advisor to [Secretary of Defense Caspar] Weinberger, later recalled. Powell and his boss immediately set out to prevent such deployments in the future. Over the next year, the two of them crafted a long list of conditions under which U.S. forces should be deployed. What came to be called the Weinberger or Powell Doctrine was an immediate response to the debacle in Lebanon and also to the secretary of defense’s nasty, ongoing feud with [Secretary of State George] Shultz over the commitment of military forces abroad. Weinberger later conceded that it also reflected the ‘terrible mistake’ of sending forces to Vietnam without ensuring popular support and providing them the means to win. Made public in late 1984, the ‘doctrine’ provided that U.S. troops must be committed only as a last resort and if it was in the national interest. Objectives must be clearly defined and attainable. Public support must be assured, and the means provided to ensure victory. The doctrine provoked a bloody fight within the Reagan adminstration –Shultz labeled it the ‘Vietnam Syndrome in spades.’ It was never given official sanction. But top military officers staunchly supported it, and as Joint Chiefs chairman in the 1990s Powell would fight vigorously for the application of what had become a doctrine bearing his name.” (Herring, chap.19, p. 875)

Elihu Root (1845-1937)