By Brendan Birth

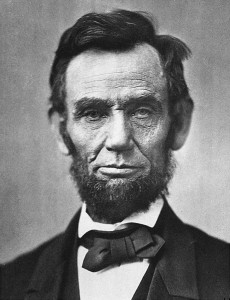

By September 1863, the Union was gradually regaining control of Tennessee. This was good news for President Abraham Lincoln, who was facing the prospect of a re-election campaign in 1864. In spite of this development, however, there were three things the president still needed to see accomplished, as of September 1863, for the ultimate success of his war policy. First, he wanted Tennessee maintained as a state in the Union, second, that emancipation was brought into the state, and third, that African Americans who lived there would be allowed to serve in the Union army.

In order to carry out these policies, Lincoln needed the cooperation of Andrew Johnson, who was then the Military Governor of Tennessee (and later became President of the United States after Lincoln was assassinated). As a result, Lincoln wrote an important letter in September 1863 letter dealing with these issues that he hoped would become a reality under Governor Johnson.[1] However, that is the key word: hope. While Lincoln wanted Johnson to embrace his agenda embraced, The Tennessee politician had been slow to act, especially on emancipation and black rights.[2] As a result, Lincoln felt the need to mobilize Johnson and to do so soon. This explains the sense of urgency which permeates this revealing confidential letter.

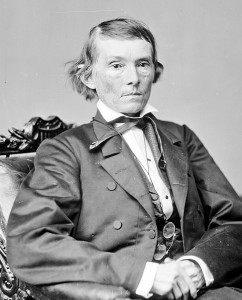

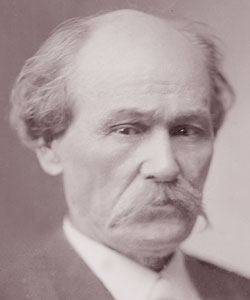

Isham G. Harris, Confederate Governor of Tennessee. Image courtesy of the House Divided Project at Dickinson College.

Naturally, Lincoln’s first goal was to keep Tennessee out of Confederate hands. Unfortunately, the historical events of 1863 made it clear that this was no easy task. With secessionists such as Isham G. Harris, the Confederate Governor of Tennessee, trying to get involved in the affairs of the state, the president had his hands full.[3] He knew that there was only one way for Lincoln and Johnson to keep control of the state out of the hands of people like Harris: by “re-inaugurating a loyal State government.”[4] Therefore, Lincoln conveyed this fact when he wrote to Johnson.

While Union control over the state was at the top of the president’s priority list, he also needed Johnson to move more quickly on emancipation. While Lincoln praised the governor because “I see that you have declared in favor of emancipation in Tennessee,” he also wanted Johnson to “get emancipation into your new State government.”[5] These quotes were based on the fact that Johnson was pro-emancipation at the time yet unwilling to enact this policy within his state government. As a September 8, 1863 article in The New York Times stated, he was “on the extreme anti-slavery ground” yet believed that the people of Tennessee should be the ones to take action in freeing the slaves (not the federal government, or state governments).[6] What this article failed to mention was that Johnson was dragging his feet with the issue,[7] and that even by the time that he was in favor of immediate emancipation, “his deep-seated racial antipathies never faded away.”[8] Maybe Lincoln knew of this fact, and that as a result he felt the need to keep Johnson focused on this issue so that he did not let prejudices get in the way of emancipation.

Lincoln briefly made a third demand to Andrew Johnson: allowing African American troops to serve in the army. He bluntly made that request when he said that, “The raising of colored troops I think will greatly help every way.”[9] This had to be a jarring statement to Andrew Johnson, who has been described by contemporary biographers as “no supporter of black soldiers.”[10] Consequently, the president had to work on convincing Governor Johnson to allow African Americans in the military.

While Lincoln was pushing Johnson to do three different things, these requests shared something in common: they all involved the president asking Johnson to take action as possible. This leads one to ask why Lincoln felt such a sense of urgency.

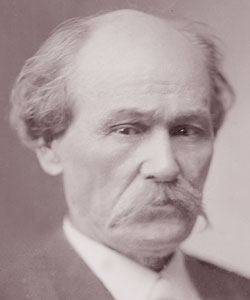

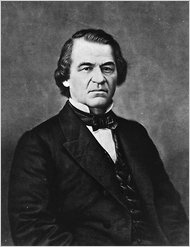

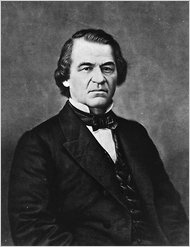

Andrew Johnson, who was the Military Governor of Tennessee at the time Lincoln wrote to Johnson. Image courtesy of The New York Times.

Part of the answer was that Johnson was slow to act on Lincoln’s agenda. With governmental issues, Johnson was hesitant to run elections in Tennessee because he feared that the Confederates would win; this concern was highlighted in Hans L. Trefousse’s biography of Andrew Johnson.[11] His problems with emancipation and African American soldiers were different. On these two issues, he was either procrastinating (as with emancipation)[12] or rejecting Lincoln’s ideas (as with not allowing African American soldiers).[13] Those actions, or a lack thereof, could explain why Lincoln felt impatient with the then-Military Governor of Tennessee.

There was another reason why Lincoln needed Johnson to act quickly: there was the potential for a new president to be elected as soon as autumn of the next year. Not only that, but it was possible that the new commander-in-chief would be hostile to what Lincoln had done. He made this clear when he said that, “It is something on the question of time, to remember that it can not be known who is next to occupy the position I now hold, nor what he will do.”[14]

Lincoln probably didn’t just mention the upcoming election for the sake of saying that he might be defeated in 1864. Instead, may’ve mentioned this in order to mobilize Johnson. By bringing up the fact that the president’s goal of bringing the Union back together (and therefore Johnson’s goal of bringing the Union back together) was in danger of being undone in the near future, Lincoln was able to convey to Johnson the fact that he needed to act soon.

But was Lincoln successful at telling Johnson that he needed to act soon? Based on other September 1863 correspondence between Lincoln and Johnson, the answer seems to be a qualified “yes.” This is for one simple reason: while Johnson’s policies reflected some of Lincoln’s policy ideals, he was still slow to act on emancipation.

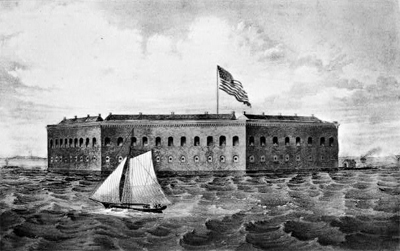

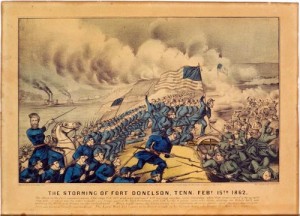

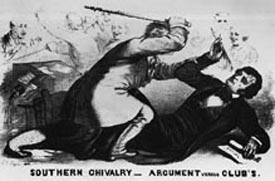

This is a depiction of the storming of Fort Donelson in Tennessee. This picture depicts the sort of invasion from outside forces that Governor Johnson wanted to avoid when he asked Lincoln to apply Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution. Image Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Johnson’s replies clearly seemed in line with Lincoln’s ideas on how to keep Tennessee in the Union. Lincoln wanted a government that was not only loyal to the Union, but one that he hoped would be “recognized here as being one of the republican form, to be guaranteed to the state, and to be protected against invasion and domestic violence.”[15] This language sounds eerily similar to the “4th section of the Constitution” that Johnson wanted Lincoln to use;[16] this section (which seems to be shorthand for Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution) has a “guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion.”[17] Less clear was the way in which he wanted this section of the Constitution applied. Did he want this provision enforced so that the federal government would take more action in Tennessee (whatever that would entail), or did he have something else in mind?

The correspondence between Lincoln and Johnson does not provide one with an obvious answer, so it’s hard to tell whether this part of the constitution was used in a substantive way in Tennessee’s case. Nevertheless, the president responded positively to the idea of using Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution in the way that Johnson wished.[18] Lincoln even elaborated on how he wanted Johnson “to exercise such powers as may be necessary and proper to enable the loyal people of Tennessee to present such a republican form of state government.”[19]

Clearly, the president was able to mobilize Johnson on how to keep the state in the Union. At the same time, he seemed to successfully convince Johnson that African Americans should serve in the military. This was what Johnson said about that issue:

“If we were authorized to offer $300 in addition to the present bounty to loyal masters consenting to their slaves entering the service of the United States it would be an entering wedge to emancipation, and for the time paralyzing much opposition to recruiting slaves in Tennessee, the slave to receive all other pay and his freedom at the expiration of term of service.”[20]

He was finally addressing Lincoln’s desire for African American troops to serve in the military. He did this by seemingly implying that, if slave masters took the appropriate action, they could have slaves fight in their place (hence opening the door for African Americans to serve in the military).

But it was not just enslaved African Americans who were encouraged to join the military. A September 27, 1863 newspaper article from the Nashville Union (a newspaper clipping which Johnson sent to Lincoln) mentioned recruitment of African Americans to serve in the military, both slaves and free persons alike.[21] This was a change-in-tune from Johnson’s former opposition to allowing African Americans in the military.

A Civil War recruitment poster for slaves, albeit not for Tennessee. This is the sort of recruitment that one would expect from Governor Johnson and Tennessee after he allowed African Americans to serve in the military. Image courtesy of archives.gov.

This action would have almost immediate consequences. On October 3, 1863, just a few days after correspondence between Lincoln and Johnson ended, African American soldiers were for the first time recruited in Tennessee.[22] Based on the timing of this War Department order, it almost seemed like the president was waiting for Governor Johnson to declare his support for such a measure.

This evidence indicates that Lincoln got his wish on African Americans serving in the military. At the same time, the quote from a few paragraphs ago also shows that the president did not get his wish on slavery. Instead of getting emancipation in Tennessee State Constitution, the president instead got military service from slaves, which Johnson considered a “wedge to emancipation.”[23] In other words, Lincoln failed to get immediate emancipation as he requested, but military service for African Americans, which might lead to emancipation later (gradual emancipation).

Indeed, Tennessee took a long time to act on Lincoln’s request for immediate emancipation. He asked for this in his September 1863 letter to Johnson, but this would not come into law until February 22, 1865.[24] In other words, the September 8, 1863 New York Times article was correct when it said that the governor was in favor of emancipation (supported by Lincoln’s correspondence with Johnson, where the governor said that he was in favor of immediate emancipation)[25] yet rejected the notion that the government taking substantive action on the issue[26] (constitutionally-supported immediate emancipation didn’t happen in Tennessee until a couple weeks within the beginning of his vice presidency).[27]

Lincoln got some, but not all, of what he requested for in his September 11, 1863 letter. However, one should not be overly critical of the president for not getting quite everything he wanted out of Johnson. While he didn’t get constitutional emancipation out of the governor, he got much more if he should have expected. Sources like Aaron Astor’s Disunion piece in The New York Times make some imply that Johnson would procrastinate on issues such as emancipation and getting African American soldiers into the army,[28] yet he had devised a plan for both issues (albeit not having immediate emancipation, but a more gradual one) within 2 1/2 weeks of beginning his correspondence with the president. For that reason, Lincoln should get credit for his ability to convince even skeptics to follow many of his plans.

Footnotes:

[1] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

[2] Aaron Astor, “When Andrew Johnson Freed His Slaves.” The New York Times, August 9, 2013.

[3] Sam Davis Elliott, Isham G. Harris of Tennessee: Confederate Governor and United States Senator. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2010: 146-47.

[4] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

[5] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

[6] “State Unity and Emancipation: Governor Johnson of Tennessee.” The New York Times, September 8, 1863: 4.

[7] Aaron Astor, “When Andrew Johnson Freed His Slaves.” The New York Times, August 9, 2013.

[8] Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1989: 196.

[9] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

[10] Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein and Richard Zuczek, Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001: 31.

[11] Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1989: 170-171.

[12] Ibid, 171.

[13] Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein and Richard Zuczek, Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001: 31.

[14] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Andrew Johnson, “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 17, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[17] “The Constitution of the United States,” Article IV, Section 4. Accessed at https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/articleiv. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[18] Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 19, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 468. Vol 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[19] Abraham Lincoln, “Enclosure to Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 19, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 469. Vol 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[20] “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 23, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[21] “The Northwestern Railroad.” Nashville Union, September 27, 1863. Accessed at The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[22] University of Maryland Freedmen and Southern Society Project, “Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War.” Revised May 21, 2014. Accessed June 20, 2015.

[23] “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 23, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[24] University of Maryland Freedmen and Southern Society Project, “Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War.” Revised May 21, 2014. Accessed June 20, 2015.

[25] Andrew Johnson, “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 17, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

[26] “State Unity and Emancipation: Governor Johnson of Tennessee.” The New York Times, September 8, 1863: 4.

[27] University of Maryland Freedmen and Southern Society Project, “Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War.” Revised May 21, 2014. Accessed June 20, 2015.

[28] Aaron Astor, “When Andrew Johnson Freed His Slaves.” The New York Times, August 9, 2013.

Bibliography:

Astor, Aaron. “When Andrew Johnson Freed His Slaves.” The New York Times, August 9, 2013. Accessed at http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/09/when-andrew-johnson-freed-his-slaves/?_r=0. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Elliott, Sam Davis. Isham G. Harris of Tennessee: Confederate Governor and United States Senator. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2010: 146-47.

Johnson, Andrew. “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 17, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Johnson, Andrew. “Andrew Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 23, 1863.” In The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Lincoln, Abraham. “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 11, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 440-441. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed March 4, 2015.

Lincoln, Abraham. “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 18, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 463. Vol. 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Lincoln, Abraham. “Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 19, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 468. Vol 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Lincoln, Abraham. “Enclosure to Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Andrew Johnson, September 19, 1863.” In The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 469. Vol 6. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R. and Richard Zuczek. Andrew Johnson: A Biographical Companion. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001.

“State Unity and Emancipation: Governor Johnson of Tennessee.” The New York Times, September 8, 1863: 4.

“The Constitution of the United States.” Accessed at https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/overview. Accessed June 15, 2015.

Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 1989.

University of Maryland Freedmen and Southern Society Project. “Chronology of Emancipation during the Civil War.” Revised May 21, 2014. Accessed June 20, 2015.

Courtesy of R.J. Norton

Courtesy of R.J. Norton