D.R. Anthony knew full well when he issued Brigade Order 26 that there could be consequences for his actions. He had directly thumbed his nose at orders from three superior officers and the U.S. Government. Anthony knew that General Mitchell was “of the old conservative school,” that was not in favor of using the Army to emancipate the slaves. However he did believed he had the enlisted men on his side. He wrote home to his sister of the support he had from the enlisted men; “When [Order 26] was read, our boys yelled — both batteries and the 8th Kansas did also…I have to take the lead, but I have the 2nd Kan and 8th Wisc batteries, the 1st 7th and 8th Kan, 2nd Illinois and the 12th, 13th, and 15th Wisconsin volunteers to back me” Anthony had struck his blow against slavery, and with the support of his men and belief in the rightness of his actions he did not fear the wrath or Generals Mitchell, Quinby or Halleck. He promised Susan “you see I have little or nothing to fear in fighting brigadiers.”

Unfortunately for Anthony, it quickly became apparent he may have been wrong. When General Mitchell returned from his leave and learned of Order 26, he ordered Anthony to countermand it. The following exchange has been featured in works on D.R. Anthony since the 1870s. Historian Stephen Starr doubts it really happened, but includes the conversation all the same because it is so dramatic and, if true, so unique:

Gen. [Mitchell]. — “Col. Anthony, you will at once countermand you brigade order No. 26.”

Col. A. — “As a subordinate officer it is my duty to obey your orders, but you will remember, General Mitchell, that Order No. 26 is a brigade order, and I am not now in command of the brigade. Of course you are aware the lieutenant colonel of a regiment cannot countermand a brigade order?”

Gen. M. — “Oh, that need not stand in the way, Colonel Anthony. I can put you in command long enough for that.”

Col. A. — “Do you put me in command of the brigade?”

Gen. M. — “Yes, sir.”

Col. A. — “You say, General Mitchell, I am now commanding officer of this brigade?”

Gen. M. — “Yes, sir, you are now in command.”

Col. A. — “Then sir, as commanding officer of this brigade I am not subject to your orders; and as to your request that Order No. 26 be countermanded, I respectfully decline to grant it. Brigade order No. 26 shall not be countermanded while I remain in command.”

Regardless of the truth behind this exchange, Anthony was arrested almost immediately. He apprised his father of the situation on July 8, 1862; “I arrived here on Sunday the 6th fromColumbus, Kentucky, 145 miles by the Mobile & Ohio railroad with orders to report to General Halleck in arrest. What they will make of it, I don’t know…The most that can be done will be a court martial, and cashiered. In that case I shall go to Washington and redress and will get it, too…They know the whole country would side with me” (State Library of Kansas)

Anthony had been taken to Corinth, MS, site of the famous “Crossroads of the Confederacy,” where he was quartered at the Tishomingo Hotel. In his writings it is plain to see the optimism and conviction that shaped his life – he had no fear of what Halleck could do to him because he believed he was in the right to be freeing slaves. Halleck and others didn’t see it quite that way. Quinby’s Order 16 already stipulated that any Officer who violated it would be mustered out.

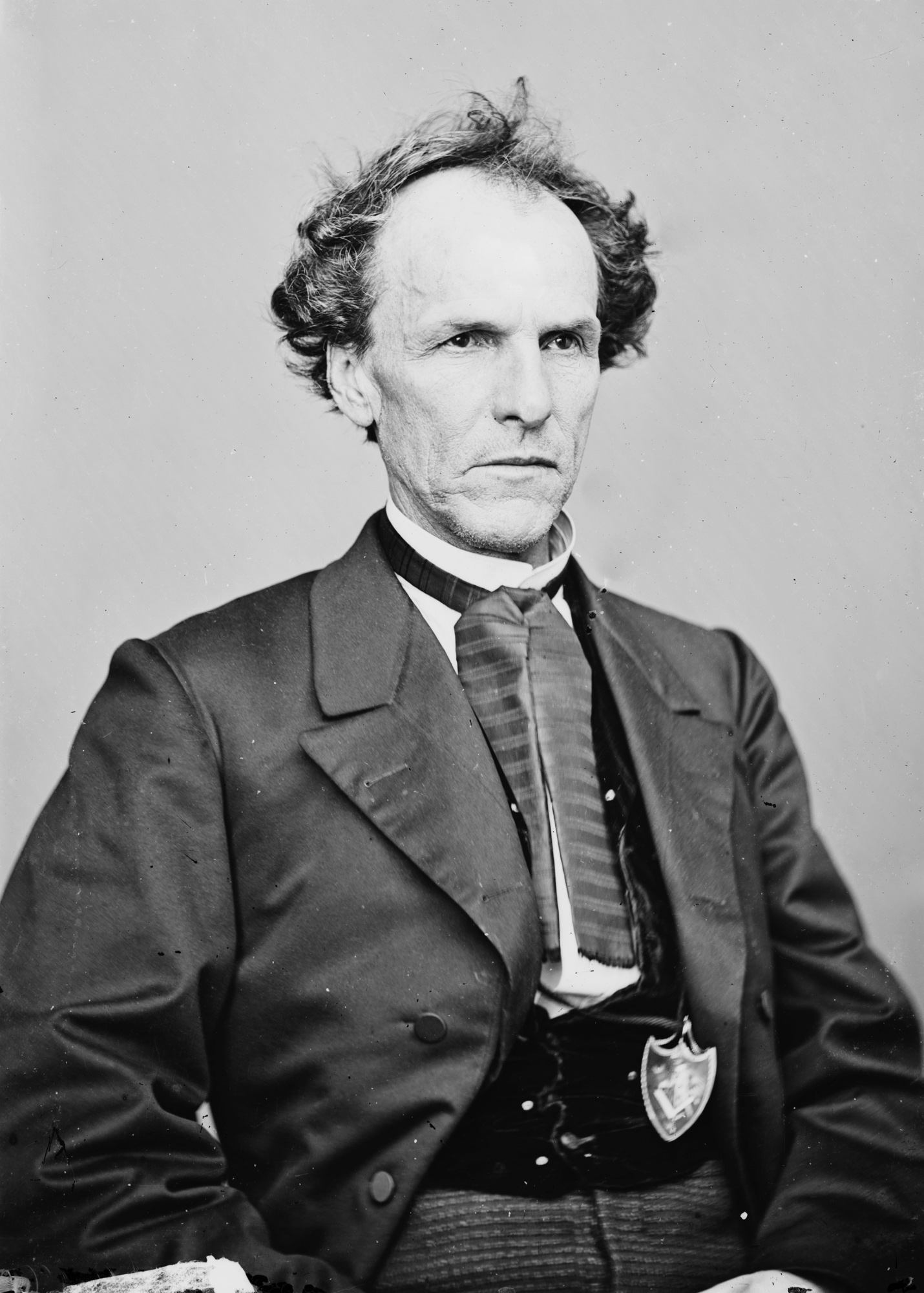

Despite his violations of orders, Anthony had correctly prophesied that his case would generate interest in Washington. Kansas Senator Jim Lane (right), an old friend from  Bleeding Kansas days, took up Anthony’s case. The Daily Cleveland Herald briefly described the senate proceedings in a July 15 article. The result was Anthony’s release and reinstatement as a Lt. Col, something that would have made an average man happy. D.R. Anthony was no average man, and what happened next must have stunned all but his closest friends and family.

Bleeding Kansas days, took up Anthony’s case. The Daily Cleveland Herald briefly described the senate proceedings in a July 15 article. The result was Anthony’s release and reinstatement as a Lt. Col, something that would have made an average man happy. D.R. Anthony was no average man, and what happened next must have stunned all but his closest friends and family.

Shortly after his reinstatement and release, Anthony submitted his resignation. Always a man of great ambition, he was motivated by two factors. Firstly, in spite of Congress’s generous reinstatement, he was unwilling to continue serving in an army that did nothing about slavery. In the same July 8 letter to his father he said “Under all these circumstances I think the army is better off without me than with me. And I shall have no heart to work until the policy…changes” When his first resignation was rejected, he tried again. Finally, his resignation was accepted, and in September, 1862 D.R. Anthony left the Army for good, ending his short, but dramatic military service.

Source:

Richmond, Langsdorf and. “Letters of Daniel R. Anthony, 1857-1862 – Continued.” Kansas Historical Quarterly 24, no. 3 (1958).

Starr, Stephen Z. Jennison’s Jayhawkers. Baton Rouge, LA: Lousisiana State Univ. Press, 1973.

Hello,

Really interesting! I didn’t know about this army officer. He was very brave!