One of the chief characters who frequently appears alongside Daniel R. Anthony is Charles Rainsford Jennison. He and Anthony served alongside one another during the Civil War, but their relationship was often strained, and they eventually became rivals as the different factions of the old free state majority fought for control of Kansas. During their time in the army, Jennison was the “spiritual” leader of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry; officially the commanding officer, he helped provide its abolitionist animus and set the tone for its early activities. However, he was an absent commander, allegedly spending much of the first 8 months of the war away from the fighting, passing his time at poker. Anthony was present with the regiment until his arrest in June of 1862, and was its day to day leader, occasionally receiving Jennison’s instructions from afar.

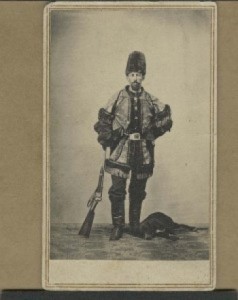

As commander of the 7th Kansas, Charles Jennison (pictured above) saw the regiment unequivocally as his, even though he was an absent commander. Anthony frequently bragged about havimg greater skill in maneuvering his men. (courtesy, Kansas Historical Society)

Anthony chafed under Jennison’s leadership and took a dim view of his qualifications. In a February letter to his brother-in-law, he wrote “Jennison has done everything I have asked of him…but he is in reality unfit for any position on account of his poor education…the prestige he has is his name – which is worth a great deal.” Simeon Fox would later relate a story to William Connelly, secretary of the Kansas Historical Society, in which Anthony had a soldier confined under guard for breaking regulations about caring for the horses. When the soldier in question was freed by his comrades, it precipiated a showdown between Anthony and the men under his command. Guns were drawn, and, as Fox tells it, only Jennison’s timely arrival prevented violence.

One of the side effects of the Seventh’s command arrangement was substantial confusion as to who exactly to blame for the Seventh’s wanton destruction and aggressive policy of slave emancipation. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton named Jennison as the leader of the unit in a letter to Missouri politicians who were complaining about the treatment of pro-Union civilians. Union General Henry Halleck credited Anthony with most of these same outrages. Later generations have not been immune to this either. In Cass County and neighboring areas of Missouri, the lone chimneys that remained after house’s belonging to secessionists were burned (giving rise to the area’s moniker ” the burnt district”) were known as “Jennison Tombstones.” Certainly both deserve the fame, or infamy, due them for their prosecution of the war in Missouri.

Jennison was arrested by military authorities in February, 1862 on the not uncommon charge of using inflammatory language towards President Lincoln and other Union officials, and for suggesting that the regiment would disband if he (Jennison) were to resign. According to historian Stephen Starr, Anthony and his fellow officers played a role in Jennison’s arrest. It is no secret that Anthony greatly coveted command of the 7th Kansas Cavalry, which he received as a result of Jennison’s absence and Anthony left the regiment in September of that year, never to return. Both returned to Leavenworth, where Anthony made his first serious foray into politics, becoming Mayor of Leavenworth in April, 1863. Jennison eventually found his way back into a military capacity, first as a leader among a group of pro-Union vigilantes known as a “Red Legs,” and later as commander of a new regiment, the 15th Kanas Cavalry.

As Mayor, just as in the Army, Anthony ruled with a firm hand. When Anthony resisted Union General Thomas Ewing Jr’s declaration of martial law in Leavenworth, Jennison and George Hoyt, a former Captain of the 7th who worked with Anthony to free slaves, let him know exactly how they felt about their former fellow officer: “let it be remembered that while we were friendly to the nomination of the mayor…we did not subscribe to any express or tacit endorsal [sic] of those gross and tyranical [sic] userpations [sic] of authority which have all along marked his official career in this city.” Both would oppose Anthony when the latter ran for reelection the following April. Voting in that election was marred by riots during which Anthony and his supporters were intimidated, and the incumbent mayor himself physically accosted.

Albert L. Lee took over the 7th Cavalry after Anthony resigned. He went on to become a Brigadier General, and commanded Cavalry during the siege of Vicksburg.

The point illustrated in this relationship is that the majority which brought Kansas into theUnion as a free state, and which was so unified by its common enemy – slavery – suffered from quite a lot of infighting. Once status as a free state was secured, Kansas Republicans (and the vanishingly few Democrats who remained) divided bitterly over several issues. Rivalries between major political players (Jim Lane and Charles Robinson), civilian and military authorities (D.R. Anthony and General Thomas Ewing Jr) and within the military itself (General Ewing and General Blunt, or Anthony and Jennison) all created rifts within the state. The White Cloud Chief recognized the damage done by these rifts when it recommended Albert L. Lee for Congress. Lee was a former Major under Anthony in the 7th Kansas who superseded Anthony after the latter’s arrest. Anthony, true to form, deeply resented Lee as well, but because all of the scandals and infighting had “all passed over without dragging him [Lee] in,” the Chief thought he would make an excellent candidate.