(courtesy, Kansas Historical Society)

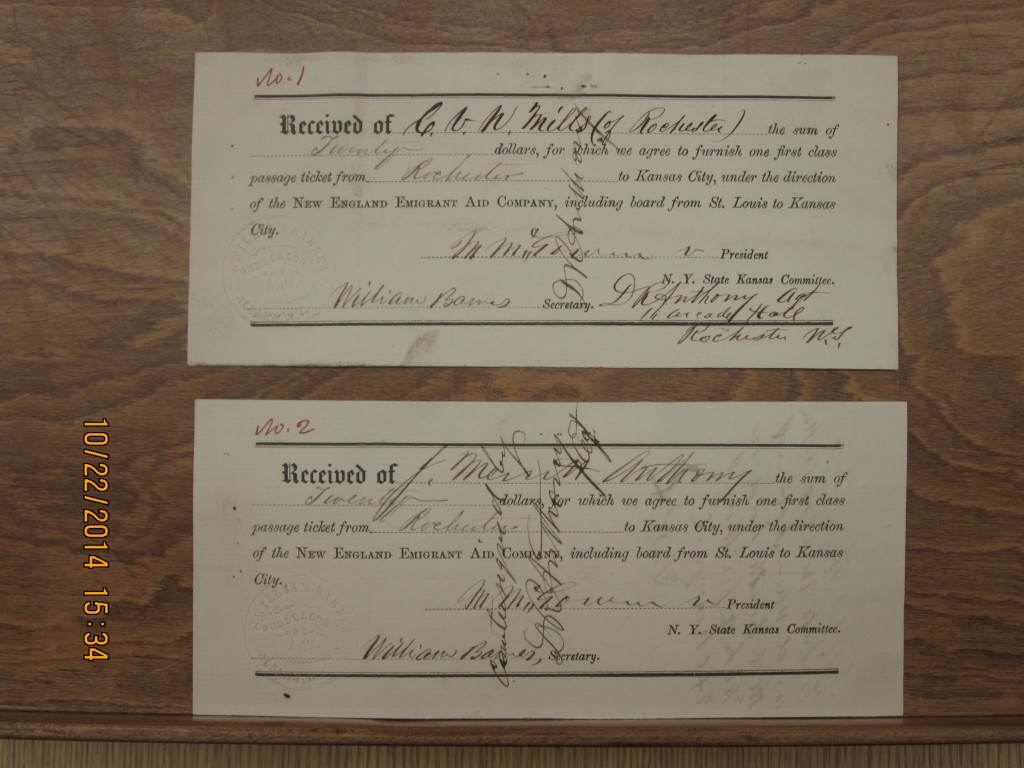

During the time between his first trip to Kansas in 1854 and his subsequent permanent move their in 1857, Anthony continued working to ensure Kansas’ entrance to the Union as a free state. He worked closely with the New York State Kansas Committee, (NYKC) an organization similar in purpose and loosely affiliated with the New England Emigrant Aid Company. Some of the best documents related to the NYKC are held in the William Barnes collection at the Kansas State Archives in Topeka, KS. Barnes was the secretary for the Committee, and managed one of its most important tasks; providing tickets to people who wished to emigrate to Kansas. According to Barnes’ log books, and his own letters, Anthony served as a point man of sorts for the Rochester and Buffalo areas of New York. In some cases, he may have fronted the funds himself, with the understanding that the would-be emigrant would repay him. Pictured below are two tickets furnished by the NYSKC . One is for an individual named “Mills” from Rochester, the other for Jacob M. Anthony, Daniel R. Anthony’s younger brother, and the youngest of the Anthony children.

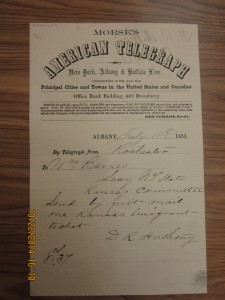

Anthony requested tickets by writing to Barnes, or via telegraph’s such as the one pictured at left. All in all, he likely secured tickets for 10-15 people wishing to go to Kansas. (courtesy, Kansas Historical Society)

For many individuals, going to Kansas was simply a means to achieve a fresh start. For others, it was a way to fight against slavery. Like much of that great moving target known as the “frontier,” it attracted men and women from different levels of society, all of whom were looking for something, were willing to fight for their future, and expected take an active role in shaping the state they lived in. This is a huge part of why the doctrine of popular sovereignty proved so critical to Kansas; it (theoretically) placed a great deal of power directly in the hands of the people, which was what they expected in the first place. It was the moment when Missourians appeared to try and deny this right to participation in government – which had been so explicitly promised in the Kansas-Nebraska Act – that Kansas elbowed its way into the avant-garde of the crusade for greater equality. The above documents are another instance where D.R. Anthony’s story weaves in and out of the larger narrative of Kansas’ quest for statehood. Organizations like the NEEAC, or the NYSKS were not unlike modern volunteer organizations; they were minutely organized, down to county and town chapters in the case of New York. Without the efforts of people like Daniel R. Anthony or William Barnes who organized and sustained these organizations, or the courage of the men and women who received tickets, the Kansas story could have been very different indeed.

Sources and Further Reading

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas : Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

William Barnes Collection, Manuscripts, Kansas Historical Society

Nicole Etcheson’s book is a superb and relatively recent treatment of the subject of Bleeding Kansas. Here are two others from past decades.

Rawley, James A. Race an Politics: “Bleeding Kansas” and the Coming of the Civil War. Philadelphia/New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1969.

Watts, Dale. “How Bloody was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in Kansas Territory, 1854–1861.” Kansas History 18, no. 2 (1995): 116–129.