“Hoover had been born in nineteenth-century Washington, D.C., a southern city that stayed segregated throughout most of the twentieth century…He presided over an Anglo-Saxon American, and he aimed to preserve and defend it.”- Tim Weiner, Enemies, 199

When most people think about the FBI and its relationship to race in America, most think of their detailed surveillance and blackmail attempts on Martin Luther King Jr. during the 1950s and 60s.[1] In fact, Weiner writes in his book Enemies, “The FBI had spied on every prominent black political figure in America since World War I. The scope of its surveillance of black leaders was impressive, considering the Bureau’s finite manpower, the burden of its responsibilities, and the limited number of hours in a day.”[2]

The extensive and complete FBI files on Martin Luther King Jr. can be seen in the FBI online archives here: http://vault.fbi.gov/Martin%20Luther%20King%2C%20Jr.

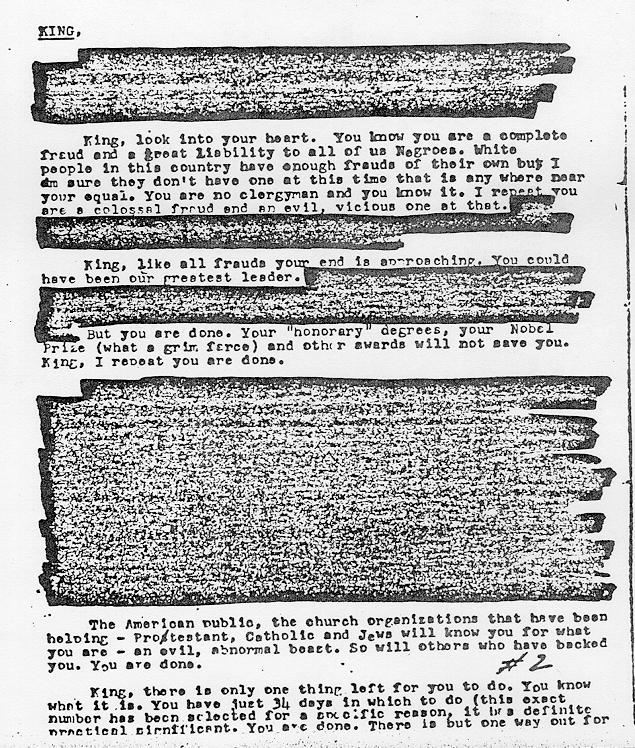

Here is a scan of the letter, manufactured by the FBI, urging Martin Luther King Jr. to commit suicide in light of the discoveries of FBI investigations

However, for reasons other than politics, Hoover had very pointed views on race that became apparent to anyone who knew him. FBI agent William Sullivan wrote in his memoir about his class of recruits who all joined the Bureau in 1941. He says, “As I took a look at my classmates, I started to notice a certain sameness about the fifty of us. Although we came from ever part of the country and from every type of background, there were no Jews, blacks, or Hispanics in the class. I was later to learn that this was Hoover’s policy.”[3] African-Americans would not be formally admitted under the payroll of the FBI until the late 1940s when the Bureau was desperate to get moles and informants inside various organizations like the NAACP.

Besides Hoover’s own personal prejudices, the FBI did have other reasons to look into the political affiliations of African-Americans. Since before World War II, some African-Americans in the American South had fallen under the charms of communism because of its promotion of racial equality. This concerned the FBI and because of it, they turned their great propaganda machine toward the south. Despite Hoover’s personal racism, a chapter of his book Masters of Deceit is dedicated toward convincing black communities that the communist cause abandoned them years earlier. He writes, “The World War II period found the party cynically abandoning any alleged struggle for Negro rights. The aim was to help not Negroes but Moscow.”[4]

Anyone who is familiar with the history of the FBI might rebut by saying that the FBI had also surveyed and harassed white supremacist groups like the Klu Klux Klan and were therefore devoid of an official racial bias. Weiner again provides interesting information. He writes, “Despite the violence, Hoover took a hands-off stance toward the KKK. He would not direct the FBI to investigate or penetrate the Klan unless the president so ordered.”[5]

Whether motivation came from the perceived vulnerability of the Civil Rights movement to communism, or from Hoover’s own prejudices, it seems apparent that the FBI had a very tense relationship toward race in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s.

[1] David J. Garrow, The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr., New York: Penguin Books, 1981. Pp. 152.

[2] Tim Weiner, Enemies: A History of the FBI. New York: Random House, 2012. Pp. 197.

[3] William Sullivan, The Bureau: My Thirty Years in Hoover’s FBI. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979. Pp. 16.

[4] J. Edgar Hoover. Masters of Deceit: The Story of Communism in America and How to Fight it. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1958. Pp. 245.

[5] Weiner, 199.