The last time I worked with lists of words in alphabetical order from another period, I was studying Spanish monolingual dictionaries from the 18th century, and what I most enjoyed from them at the time were the definitions of animals, as I found them amusing and they made me think about how different the notions of dictionary then and nowadays are. In the case of The Historie of foure footed beastes, what drew me to it was that it seemed like an antiquity containing eye-catching illustrations; it reminded me of my earlier experience and motivated me to a closer study of the book, even though it doesn’t identify itself as a dictionary (the first English dictionary, by Robert Cawdrey, appearing in 1604, then followed by Samuel Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language, in 1775).

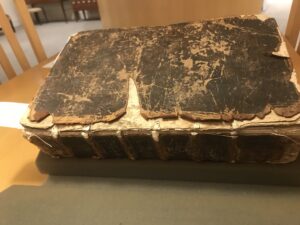

When reading this book, the overwhelming documentation used to write the descriptions of the creatures listed in it leaps out. The book refers to classic texts, provides an exhaustive list of authors and sources consulted, and gives an account of the names of the species discussed in different languages. It is a book that, for reasons that I later analyze in detail, seems to have been conceived for a didactic purpose. Holding it, having it in my hands, is not easy because of its large size (22 x 33 x 8 cm. / 9 x 13 x 3 inches, approximately) and its very poor state of preservation, which makes it a delicate object to handle and observe carefully but which also shows the great use that has been given to it.

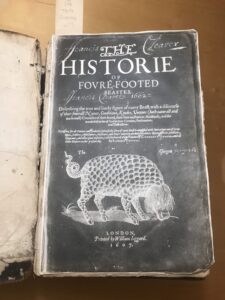

There is no information on the book’s covers nor its spine about the title. In this case, a Xerox of what is believed to be the title page gives information about this book, although it may not be this edition. In the back of the print, presumably made by the archivist or owner of the book, “Library of Congress” is written down, specifying where this first page was xeroxed. That is to say, this book does not preserve its first title page, but furthermore it has in its place information from a book that does not match this one. The reason for this affirmation is that, in the copy, only includes the title of the first book of living creatures: The Historie of foure footed beastes (see Figure 1), first published in London, in 1607, but the book that is here being described includes a second part, published originally in 1608, entitled The Historie of Serpents. Or, The second Booke of living Creatures. What we know: both parts were written by Edward Topsell, and printed and edited by William Jaggard. But what is the title, then, of the copy kept in the Archive? One option is that this volume could have been one of the 1658 copies of History of Four-Footed Beasts and Serpents, published more than thirty years after Topsell’s death, but that volume was printed by E. Cotes, for G. Sawbridge, not by Jaggard. This leads me to think that it is a previous copy of a volume including the two books, maybe as a selling technique conjured by the printer, previous to the actual 1658 copy that brought them together after the author’s death. Apparently, Topsell had planned to publish four parts of this history of living creatures, one on four-legged beasts, one on snakes, and later on, birds and fish. However, as G. Lewis would comment on the matter: «Signs of haste, and perhaps of boredom, are evident already in the book on serpents. Despite the fact that Topsell lived on for another twenty years, the intended volumes on birds and fishes never appeared» (Lewis).

Figure 1

Edward Topsell was notably enough no zoologist, but a clergyman who borrowed and translated from Latin to English mainly Konrad Gesner’s well-known bestiary, Historia Animalium, in order to compose these works.The collaboration with Gesner would be proved by the fact that Gesner includes an Epistle “To the Reader” as part of the front matter of Topsell’s text, although it is still a matter to be explored in depth.

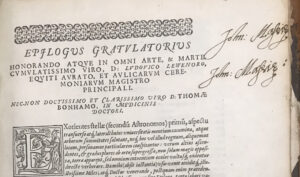

The Historie of Foure Footed Beastes has a front matter consisting of the missing title page, a dedicatory letter to reverend Richard Neile, the letter from Gesner “To the Reader”, one from Topsell “To the learned Reader”, a catalogue included by Topsell with all the authors that had previously written about the beasts, a Latin catalogue of the same content, and an “English Table” with the names of every four-footed beast that he knew of (including, interestingly enough, unicorns, of whom he expressed his disbelief but nevertheless importance as a recurrent creature in other texts). The Historie of Serpents is separated from its first part of four-footed creatures by two blank sheets. Its front matter consists of a dedicatory letter addressed, once more, to reverend Richard Neile, a letter to the reader by Topsell, a “Table of the severall Serpents, as they are rehearsed and described in this Treatise following”, and the so called “Generall Treatise of Serpents”, followed by the text in itself (and its questionable –at least from today’s point of view– idea of serpents; one of them being bees included in the serpent category). In the back matter, there is an “Epilogus Gratulatorius” entirely written in Latin, where Ludovico Leonoro and Thomo Bonhamo are praised, followed by “A table of the names of al the Foure-footed-Serpents” and “A table of all the Latine names of Serpents without legges, as well corrupted as those in use”, meaning that he included the classical Latin terms along with those used in the Vulgar Latin language.

E. Willoughby is the name that links this particular copy to the Archive, as it was donated to the library by the Willoughby family, in memoriam. This information can be found in the front paste-down endpaper which has a stamped card on it. (See Figure 2)

Figure 2

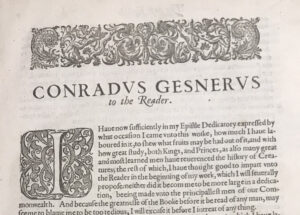

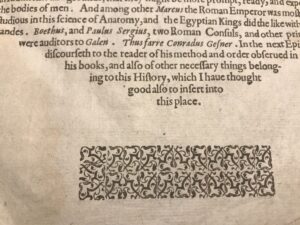

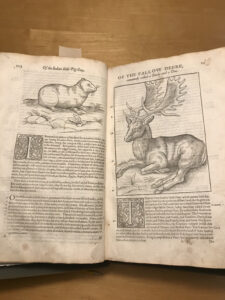

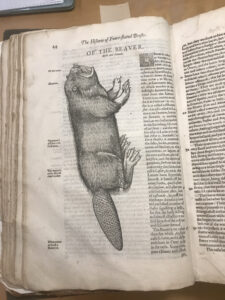

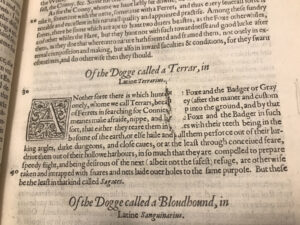

Inside the book, illustrations are of great importance (Figures 3, 4), as well as the ornaments at the beginning and at the end of some sections displaying floral and animal motifs (Figures 5, 6), all produced by wood engravings ––the artist of the woodblocks is unknown. In terms of the content of the pages, the book has larger margins on the outer side, and small font in the main text, although it is changeable depending on the section (e.g. “OF THE DOG” and “Of the the biting of a mad Dog”).

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The display or layout of the page is diverse and the illustrations are framed within the text differently every time (Figures 7, 8).

Figure 7

Figure 8

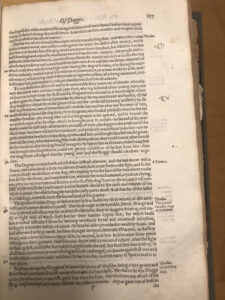

Noteworthy elements can be found reading a regular page from the main text of either book. Such elements are catchwords in the end of some initial and ending pages used to ensure that the manuscript would be assembled correctly (Figure 9); letters under the footline of some pages known as signatures and meant to serve as indicators of the correct order of sheets when the book is arranged (also see Figure 9); headers indicating different sections in every page; quotation marks placed at the outer margin of the page whenever long verbatim citations were included (Figure 10); the names of authors cited and other key words printed at the outer margins too (see also Figure 10), that served presumably as a guide to the reader, maybe another technique meant to facilitate quick referencing, to indicate at a glance where more specific information is located in the text, like the fact that the text is numbered every 10 lines in the center of the page.

Figure 9

Figure 10

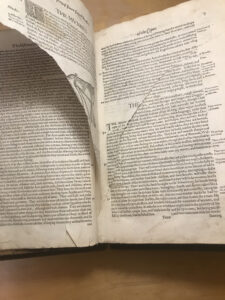

The entire book seems to have had a very useful life, with numerous stains, signs of aging and deterioration, as well as the negative effects of water stains and brittle, scuffed edges, cracked sides, holes and even ripped pages. (See the following figures 11, 12, 13):

The book binding is some sort of thinned leather folded around a piece of hard cardboard that was laced-in, and is separated from the rest of the codex but for one binding chord that kept it from falling apart completely. Most of the leather from the sides and spine is eroded, exposing the pieces on the inside of the binding, as is appreciated in the following images:

Figure 14

Figure 15

The pages are of a very thin, fragile paper, whose quality is questionable since it bleeds through and lets us see the text of the verso from the recto side. It also does not seem to have been taken care of even when it was printed, as I came upon a detail in which the paper has torn and no letters have been printed on that piece (Figure 16).

Signs of use throughout the whole book include marginalia such as scribbled notes, drawn manicules that indicate relevant sections for the reader (Figure 17), underlined sections in pen ink, various “X” marking an important line, but also ink stains, pencil marks resulting from having pointed without intending to write anything or to point out a specific point, and clumsily written shapes in pencil that are constantly repeated on the last page of the book. These last ones remind us of a bored child or student repeating the same drawing over and over again in his book (Figure 18).

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

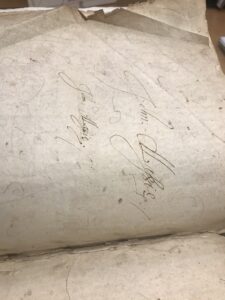

On a final note, there are several inscriptions of a not very readable signature, two of them in the back free endpaper, written in colored ink, that could have been made by the same hand that drew the manicules and the underlined parts in ink in the book (Figure 19), and another two with same ink in the “Epilogus Gratolatorius” (Figure 20). A theory for their existence is that they were part of some kind of testing of the paper’s quality, a seemingly normal practice at the time, as in our time checking the ink of a pen making a doodle in the page would be.

Figure 19

Figure 20

Works consulted and cited

“Glossary of Manuscript Terms.” Folgerpedia, https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Glossary_of_manuscript_terms.

Greenfield, Jane. ABC OF BOOKBINDING: An Unique Glossary with over 700 Illustrations for Collectors & Librarians. Oak Knoll Press, 1998.

Isaac, Susan. “The Familiar and the Fantastic: The Historie of Foure-Footed Beastes by Edward Topsell, 1607.” Royal College of Surgeons, 16 Mar. 2018, https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/the-familiar-and-the-fantastic/.

Lewis, G. “Topsell, Edward (Bap. 1572, d. 1625), Church of England Clergyman and Author.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sept. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-27557?rskey=5wM8rj&result=1.

Mulley, Jessica. “Book Descriptions: Glossary of Terms.” BookAddiction, 23 Dec. 2022, https://bookaddictionuk.wordpress.com/book-collecting/book-descriptions-glossary-of-terms/.

Nicholson, James B. A Manual of the Art of Bookbinding Containing Full Instructions in the Different Branches of Forwarding, Gilding, and Finishing ; Also the Art of Marbling Book-Edges and Paper ; the Whole Designed for the Practical Workman, the Amateur and the Book-Collector. Henry Carey Baird, 1856.

Poortenaar, Jan, et al. The Art of the Book and Its Illustration. Harrap, 1935.

Wells, Stanley. “Jaggard, William (c. 1568–1623), Printer and Bookseller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sept. 2004, https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37592?rskey=RbFE6I&result=1.

Willoughby, Edwin Elliott. A Printer of Shakespeare; the Books and Times of William Jaggard. Haskell House, 1970.