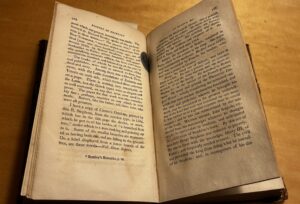

The Token and Atlantic Souvenir: An Offering for Christmas and the New Years is a gift book featuring a collection of prose, poetry, and illustrations. Gift books, unlike regular books, catered primarily to women and young girls, emphasizing aesthetic appeal over content. These books featured elaborate bindings and luxurious materials, serving as decorative objects meant for display rather than reading. The Token and Atlantic Souvenir embodies the gift book tradition, featuring works from renowned writers like Henry Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Samuel Griswold Goodrich. Though many writers contributed to the book, these four are the most well-known.

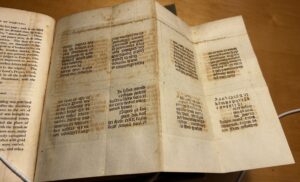

Figure 1: Contents

Henry Longfellow, one of the most famous contributors, was a celebrated American poet, known for works such as “Paul Revere’s Ride,” The Song of Hiawatha, and Evangeline. Longfellow was a member of the Fireside Poets, a group cherished in New England for their focus on themes of mortality and domesticity. His poem “The Two Locks of Hair” is featured in The Token and Atlantic Souvenir.

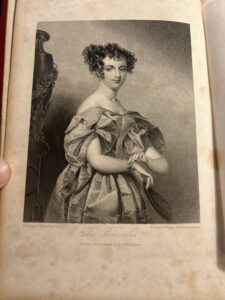

Figure 2: The Two Locks of Hair

Another prominent contributor, Harriet Beecher Stowe, is best known for her abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe was a prolific author and social justice advocate who wrote 30 books and many articles and letters. Her poem “The Yankee Girl” is included in The Token and Atlantic Souvenir.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, known for his novels The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, also has several works featured in the gift book. He is best known for his works on history, morality, and religion. Hawthorne is one of the only writers in The Token… with multiple works featured. This shows his standing in 19th-century American literature; his works brought prestige to the gift book. His works “The Shaker Bridal,” “Night Sketches, Beneath an Umbrella,” and “Endicott and the Red Cross” are all included in the gift book.

Samuel Griswold Goodrich, who edited the annual under his pseudonym Peter Parley, included his own essay “Sketches from a Student’s Window.” Due to his work as the editor of The Token…, many people accept him as the author of the book. His efforts played a pivotal role in shaping the content of the gift book, curating works that appealed to the cultural beliefs of the time.

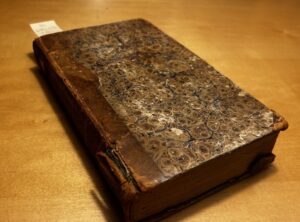

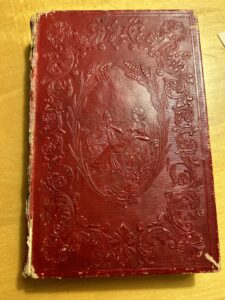

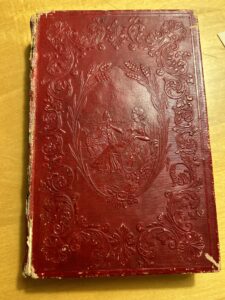

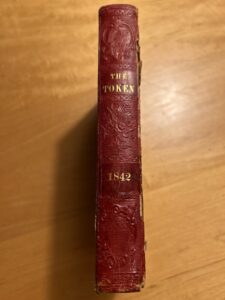

Beyond the literary contributions, the craftsmanship of the book further elevates its status. The intricate binding, high-quality parchment, and detailed engravings all showcase the gift book’s intended purpose: to be a visual and tactile display piece. The Token… likely used parchment rather than vellum or sheepskin for its binding. Parchment is smooth, with a consistent texture on either side, while animal skin has a side with hair remnants. The uniformity of the parchment enhanced the book’s elegance. The engraved cloth cover added another layer of sophistication. The New York company Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Smillie engraved the intricate artwork on the covers. The paper quality also set gift books apart from regular publications; J.M. and L. Hollingsworth are the papermakers for the book. Benjamin Bradley, one of Boston’s most skilled bookbinders, ensured that the book’s construction matched its artistic design.

Figure 3: Front Cover

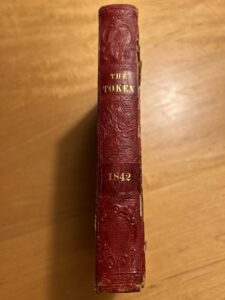

Figure 4: Book Spine

Several contributors also played key roles in the production of The Token and Atlantic Souvenir, reflecting the collaborative nature of gift books. Samuel N. Dickinson, a prominent Boston printer, was a key contributor to the project. His work earned praise for its precision and clarity, and his work helped popularize the Scotch Roman typeface in the United States. David H. Williams, the primary publisher, oversaw the Boston editions of The Token and Atlantic Souvenir. To expand the book’s reach, Williams collaborated with other publishers across the United States, as well as in England and France. These publishers were included on the title page in the book, showing readers the prestige and reach that the book had; it indicated that it was not simply a local publication, but rather popular worldwide. Many publishers allowed the book to gain popularity worldwide.

Figure 5: List of Publishers

The annual series, published from 1829 to 1842, featured new content every year, showcasing different authors and artistic styles. The variations between editions reflected changes in literary trends and advancements in printing technology. Gift books bridged the gap between art, literature, and commerce in the 19th-century. They were luxury items that reflected one’s social status, particularly that of the gift giver. The intricate designs and sophisticated content distinguished them from regular books. Gift books catered to an audience that valued aesthetic beauty and intellect, making them prized possessions in the 1800s. Through their exquisite design and curated content, gift books offered more than entertainment; they reflected the cultural and social beliefs of the time.

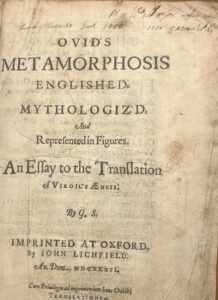

Figure 6: Ornate Title Page

Works Consulted

“Details For: The Token and Atlantic Souvenir, : An Offering for Christmas and the New Year. › Library Company of Philadelphia Catalog.” Kohacatalog.com, 2024, librarycompany.kohacatalog.com/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=277999.

Hurley, Natasha. “Typee and the Making of Adult Innocence.” Studies in American Fiction, vol. 46, no. 1, Mar. 2019, pp. 31–54. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=0b5e2281-7d17-3175-bf1d-5feb5f019117.

McGettigan, Katie. “Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and the Transatlantic Materials of American Literature.” American Literature: A Journal of Literary History, Criticism, and Bibliography, vol. 89, no. 4, Dec. 2017, pp. 727–59. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.dickinson.idm.oclc.org/10.1215/00029831-4257835.

“Rare Gift Books.” Brandeis.edu, 2024, www.brandeis.edu/library/archives/essays/special-collections/rare-gift-book.html.

“Reviews of the Token for 1842.” Merrycoz.org, 2024, www.merrycoz.org/voices/token/reviews/1842.xhtml.

Silver, Rollo G. “Flash of the Comet: The Typographical Career of Samuel N. Dickinson.” Studies in Bibliography, vol. 31, 1978, pp. 68–89. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40371675

URAKOVA, ALEXANDRA. “Hawthorne’s Gifts: Re-Reading ‘Alice Doane’s Appeal’ and ‘The Great Carbuncle’ in The Token.” The New England Quarterly, vol. 89, no. 4, 2016, pp. 587–613. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26405815

In the “To the Reader,” Alessio1 talks about his knowledge of many languages and his “singular pleasure in philosophy, and in the secrets of Nature,” adding that he travelled the world for “seven and twenty years.” He gathered his “secrets” from other learned men, noble men, “poor women, artifacers, pesants, and all sorts of men.” When Alessio was “fourscore and two year and seven months” he met a sick man, suffering from an inability to urinate. Out of his “vain glory” and fears that the physician might use his “secrets” for selfish purposes, Alessio refused share the “secrets,” and the physician, fearing others knowing he sought outside help, refused to allow Alessio to administer the medicine himself. When the man passed, Alessio was overcome with guilt, saying that he “desired to die” because he was a “murderer” for withholding his “secrets.” To help alleviate some of this guilt, he was “determined to communicate” his recipes to the public, hence this book. He assures his readers of his trustworthiness by way of his age, this story, and the promise that the recipes are “true and experimented.”

In the “To the Reader,” Alessio1 talks about his knowledge of many languages and his “singular pleasure in philosophy, and in the secrets of Nature,” adding that he travelled the world for “seven and twenty years.” He gathered his “secrets” from other learned men, noble men, “poor women, artifacers, pesants, and all sorts of men.” When Alessio was “fourscore and two year and seven months” he met a sick man, suffering from an inability to urinate. Out of his “vain glory” and fears that the physician might use his “secrets” for selfish purposes, Alessio refused share the “secrets,” and the physician, fearing others knowing he sought outside help, refused to allow Alessio to administer the medicine himself. When the man passed, Alessio was overcome with guilt, saying that he “desired to die” because he was a “murderer” for withholding his “secrets.” To help alleviate some of this guilt, he was “determined to communicate” his recipes to the public, hence this book. He assures his readers of his trustworthiness by way of his age, this story, and the promise that the recipes are “true and experimented.” I couldn’t find much on Richard Androse, one of The Secrets’ translators, but I had more luck with the other, William Ward [Warde]. Ward (1534-1609) was a physician and translator and studied at Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge (Bayne & Wallis). He served as physician for both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I (Ibid.). He also translated several works from French to English, including The Secrets (Ibid.). It is likely from his expertise as a physician that he added recipes to the English edition as he translated it (Martins).

I couldn’t find much on Richard Androse, one of The Secrets’ translators, but I had more luck with the other, William Ward [Warde]. Ward (1534-1609) was a physician and translator and studied at Eton College and King’s College, Cambridge (Bayne & Wallis). He served as physician for both Queen Elizabeth I and King James I (Ibid.). He also translated several works from French to English, including The Secrets (Ibid.). It is likely from his expertise as a physician that he added recipes to the English edition as he translated it (Martins).

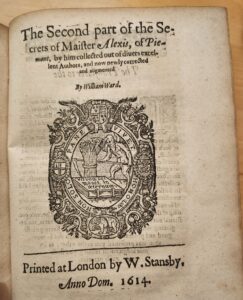

William Stansby (1572 – 1638) printed this edition in London at Cross Keys printing house. He apprenticed there under John Windet from 1589 to 1597 and then continued working with him, becoming co-partner in 1609, just before Windet’s death in 1610 (Bland). Windet focused on long print runs of small godly books, but after his passing, Stansby worked on smaller print runs of larger works and introduced more variety to the material than Windet had (Ibid.). During this period, he printed works by “John Donne, Sir Walter Ralegh, William Camden, John Selden, Michael Drayton, [and] Sir Francis Bacon,” (Ibid.) and, most famously, Ben Jonson’s first folio in 1616 (Wienberg). Stansby frequently printed banned or frowned-upon materials and was even arrested in the early 1620s for a pamphlet on Ferdinand II succeeding to the crown of Bohemia (Bland). Despite the change in focus, Stansby continued to use Windet’s printer’s device as seen on the section title pages of The Secrets (Windet). Around 1624, Stansby calmed down substantially, printing longer runs of psalms once more (Bland).

William Stansby (1572 – 1638) printed this edition in London at Cross Keys printing house. He apprenticed there under John Windet from 1589 to 1597 and then continued working with him, becoming co-partner in 1609, just before Windet’s death in 1610 (Bland). Windet focused on long print runs of small godly books, but after his passing, Stansby worked on smaller print runs of larger works and introduced more variety to the material than Windet had (Ibid.). During this period, he printed works by “John Donne, Sir Walter Ralegh, William Camden, John Selden, Michael Drayton, [and] Sir Francis Bacon,” (Ibid.) and, most famously, Ben Jonson’s first folio in 1616 (Wienberg). Stansby frequently printed banned or frowned-upon materials and was even arrested in the early 1620s for a pamphlet on Ferdinand II succeeding to the crown of Bohemia (Bland). Despite the change in focus, Stansby continued to use Windet’s printer’s device as seen on the section title pages of The Secrets (Windet). Around 1624, Stansby calmed down substantially, printing longer runs of psalms once more (Bland).