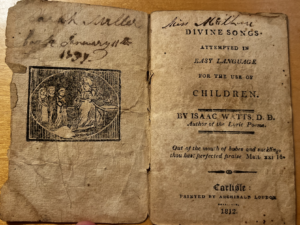

Divine Songs for Children, or more specifically, its full title Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language For the Use of Children, reveals its intended audience plainly and immediately.

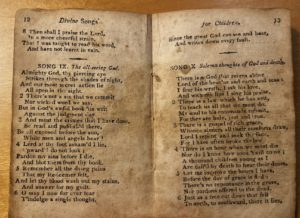

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812, Divine Songs is aimed at young, religious readers. The context of the book is straightforward; it has a title page, twenty-eight hymns, and lastly the Ten Commandments. There is nothing else. The children who would have used this book are not interested in anything else, more information or filler is boring to most children. One exception to this is illustrations. There is only one illustration in the book (a frontispiece); it is small, only taking up about a third of the page. Likely no other illustrations were added to keep production costs down, and the final price low as well.

Printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812, Divine Songs is aimed at young, religious readers. The context of the book is straightforward; it has a title page, twenty-eight hymns, and lastly the Ten Commandments. There is nothing else. The children who would have used this book are not interested in anything else, more information or filler is boring to most children. One exception to this is illustrations. There is only one illustration in the book (a frontispiece); it is small, only taking up about a third of the page. Likely no other illustrations were added to keep production costs down, and the final price low as well.

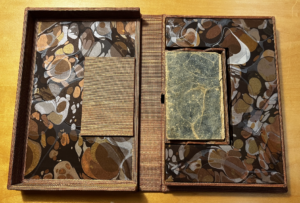

Keeping in mind the intended audience, Divine Songs was likely not very expensive. This is further supported by the modest craftsmanship of the book itself. It is simply bound; no boards were used, it is only held together with stitching. The text printed throughout the book was not done meticulously. The margins are irregular. On some pages, the text goes fully to the bottom of the page with no lower margin. On others, the text starts immediately at the top. The same inconsistency occurs with the size of the gutter. Considering that Divine Songs was deliberately made like this for its audience, its uncomplicated craftsmanship likely allowed the price to be kept relatively low. This way, the book could be realistically accessed by children.

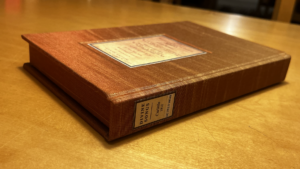

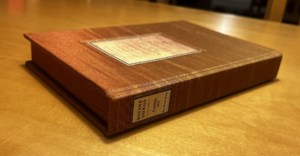

The book is very small, measuring 10.25cm x 6.8cm x 0.2cm. To visualize, when closed Divine Songs is a little shorter than the size of my hand. I have not tried it myself, but I imagine any pocket that can fit my hand would very easily fit Divine Songs. It is currently in a fragile state (212 years will do that to any boardless book), so I would not recommend anyone try it. However, being pocket-sized would have applied itself well to a life of travel, perhaps back and forth between church and home?

Hymns are songs meant to be sung in worship and are very commonly used during official services. Divine Songs has twenty-eight hymns printed in it. Some songs are more broad, such as “A general song of praise to God” and “Heaven and Hell.” Others are a lot more specific and likely personal to a child, such as “Love between Brothers and Sisters.” It has something for every occasion. The book was very likely intended to be owned and read by a child and brought back and forth from home to church or school. Hence the content and the small and easily portable size.

We know from the title that Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language For the Use of Children was intended to be used by religious children. But looking further at the author, Isaac Watts can give us a more specific understanding. Isaac Watts was a protestant minister, born in England in 1674, he is sometimes known as the “father of English hymnody” (Watts). Given that he is a very well-known protestant, the book was probably made for other protestants. However, the Church of England did not approve of hymns until 1820 (Divine Songs was published in 1812), so Anglicans likely will not purchase the book (Hymn).

We have an idea of the type of person who would have owned Divine Songs. Unfortunately, we do not have information on who this owner actually was. There is a name written in the book, very likely the name of the owner, but it cannot be read with certainty. I have talked more in-depth about Sarah in a previous blog post.

Works Cited

“Hymn.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020.

“Watts, Isaac.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020.

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from