Although Isaiah Thomas’s History of Printing in America was the first of its kind to compile American newspapers, pamphlets, books, and interviews from fellow printers to create a vital record, Thomas, the American Antiquarian Society, Benjamin Franklin Thomas (Isaiah Thomas’s Grandson), and William McCulloch continued to improve upon the original text—leading to the creation of the second edition. Two years after the publication of the first edition in 1810, McCulloch, one of Philadelphia’s leading printers, wrote letters to Thomas, later published by the American Antiquarian Society as ‘William McCulloch’s Additions to Thomas’s History of Printing” in 1912. McCulloch highlighted the numerous factual inaccuracies, mostly concerning the printing history in Pennsylvania, within the two volumes and offered corrections and improvements from simple date, number, and name corrections to paragraphs dedicated to the lives of printers. He even suggests that Isaiah Thomas get rid of certain accounts (like the paper L’Hemisphere on page 93 for its “poor catchpenny production,” Folwell’s “Spirit of the Press” and Helmbold’s the Tickler, stating on page 94 and without elaboration, “their editors are the disgrace of civilization”). Besides McColloch’s strong opinions on the previous works, he does provide invaluable information to Thomas such as on page 93 where he writes, “You relate, in one place, that there are 400 Printing Offices in America, and in another of there being 350 Newspaper establishments. Is there not some clashing in this statement?” and sharing his recording of printing houses in Philadelphia from 1803, “There were 45 offices keeping 89 presses. Of these printers, 15 were also booksellers.” Thomas’s numerous errors could be the product of being the first in America to record printing history and a lack of review from fellow printers; if McCulloch, being an experienced printer who can fact-check Thomas, never read Thomas’s book, it is likely these errors would remain unchanged and consequentially misinform readers. According to the American Antiquarian Society, two years after McCulloch sent the letter, Thomas responds with a 296-page manuscript which will lay the foundation for the second edition.

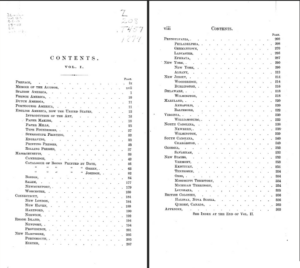

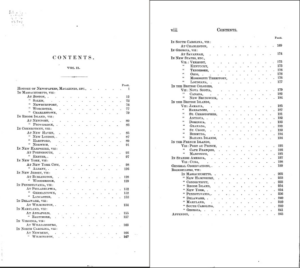

Thomas sadly passed away in 1831 at the age of 82, leaving the completion of The History of Printing in America’s second edition to his grandson, Benjamin Franklin Thomas, and the American Antiquarian Society, which was printed by Joel Munsell in 1847. The second edition heavily relied upon Thomas’s memoranda with American Antiquarian Society members, John R. Bartlett and Samuel F. Haven Jr, expanding upon Isaiah Thomas’s unfinished work. According to the preface in the second edition, one of the major changes to the first edition was Thomas’s chapters on the origins of printing in the Old World, which were omitted from the book by the society. The preface states that these chapters are “less adapted to the present state of information on that subject, as requiring too much modification and enlargement, as occupying space demanded for additional matter of an important character, and as not essential to the special object of presenting a history of the American Press.” This explains the removal of chapters such as “Origin and practice of printing in China” and “Introduction of Printing in England” and the addition of chapters titled “Spanish America,” “French America,” “Dutch America,” and “Portuguese America;” despite these chapters’ importance to print culture before America, they stray away from the title of the book and take away pages that could potentially be used for further delving into American print. Continuing, Thomas was not satisfied with his account of Spanish American Printing and wished to further expand upon it, which could potentially be due to a language barrier or overall lack of information in his collection. Therefore, society member John R. Bartlett “has given special attention to the subject” and completed Thomas’s research. Another change to the first edition that Thomas wished to fulfill was the mentioned in the preface of the first edition, in which Thomas states, “It was my design to have given a catalog of the books printed in the English colonies previous to the revolution; finding, however, that it would enlarge this work to another volume, 1 have deferred the publication, but it may appear hereafter.” Samuel F. Haven Jr., another member of Thomas’s Society, collected and examined books relating to Isaiah Thomas’s research, which he would later compile in the second edition. Despite the major difference between editions, Isaiah Thomas’s and the American Antiquarian Society’s dedication to creating a well-researched and extensive new edition shows the importance of ensuring historical accuracy.

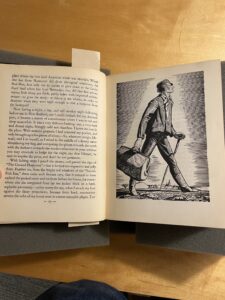

The afterlife of the book continues on with the many reprints from publishers such as Burt Franklin in 1967, Weathervane Books in 1970, Johnson Reprint Corp. in 1971, and Nabu Public Domain Reprints in 2012—all of them based on the second edition. Additionally, there are free digital copies of the first and second editions available online at the Internet Archive. To obtain a copy of the first edition of the book printed in 1810, buyers must part ways with about $3,000, according to Biblo.com, a rare book shopping website.

The History of Printing in America stands today as a testament to not only Isaiah Thomas’s dedication to history but also the efforts of William McCulloch and the American Antiquarian Society, who shared Thomas’s vision and helped him improve his work. The high prices for the physical copies of the book and the online accessibility emphasize its historical significance. The Dickinson Archive’s copy of the first edition of Thomas’s The History of Printing in America, gifted to the Belles Lettres Society by Charles Wesley Pitman in 1837—prior to the publication of the second edition—stands as a valuable book for its rich history, academic significance, and being authored by one of the greatest printers of the 1800s.

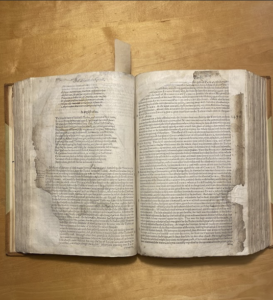

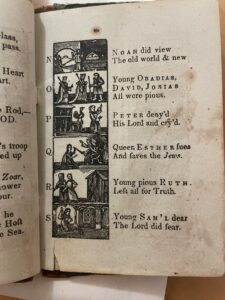

Fig. 1. The Table of Contents in volume one of the first edition of The History of Printing in America.

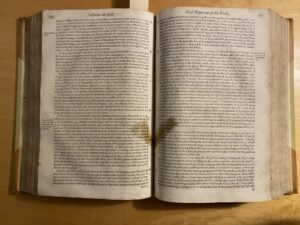

Fig 2. The Table of Contents from the second edition volume one of The History of Printing in America.

Fig. 3. The Table of Contents from the first edition of volume two of The History of Printing in America

Fig 4. The Table of Contents from the second edition volume two of The History of Printing in America.

Citations

First Folio. “THE HISTORY OF PRINTING IN AMERICA. WITH A BIOGRAPHY OF PRINTERS, AND AN ACCOUNT OF NEWSPAPERS,” Biblio, 2025, https://www.biblio.com/book/history-printing-america-biography-printers-account/d/1420818339

Accessed Feb 14, 2025

McCulloch, William. “William McCulloch’s Additions to Thomas’s History of Printing.” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society at the Semi-Annual Meeting Held in Boston, vol. 31, The Davis Press Worcester, Mass., 1912, pp. 89–100.

“Search: This History of Printing in America by Isaiah Thomas.” World Cat. Online Computer Library Center, 2025,https://search.worldcat.org/search?q=This+History+of+Printing+in+America+by+Isaiah+Thomas&author=Thomas%2C+Isaiah&itemSubType=book-printbook&itemSubTypeModified=book-printbook,

Accessed Feb 14, 2025

Thomas, Isaiah. The History of Printing in America. With a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers. To Which Is Prefixed a Concise View of the Discovery and Progress of the Art in Other Parts of the World. In Two Volumes. the press of Isaiah Thomas, jun. Isaac Sturtevant, printer, 1810.

Thomas, Isaiah, The history of printing in America : with a biography of printers, and an account of newspapers : to which is prefixed a concise view of the discovery and progress of the art in other parts of the world : in two volumes, Volume 2, First Edition, The press of Isaiah Thomas, 1810, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/historyofprintin02inthom/page/n9/mode/2up, Accessed Feb 14, 2025

Thomas, Isaiah, The history of printing in America, with a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers in Two Volumes, Volume 1, Second Edition, The American Antiquarian Society, 1847, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/aey4217.0005.001.umich.edu/page/n11/mode/2up, Accessed Feb 14, 2025

Thomas, Isaiah, The history of printing in America, with a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers in Two Volumes, Volume 2, Second Edition, The American Antiquarian Society, 1847, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/aey4217.0002.001.umich.edu/page/n5/mode/2up, Accessed Feb 14, 2025