French Cookery: The Modern Cook, by Charles Elme Francatelli, is a cookbook that was published in 1846. This book was the first of Francatelli’s four cookbooks. Francatelli was an important chef in London during this time. He was educated at the Parisian College of Cooking (Flantzer, 2018). Francatelli also served as the chef for Queen Victoria for about two years and was known for having a strong effect on the cooking community. I went more in-depth about Francatelli’s life, education, experiences, and influences in my past blog post. This specific book that I have been studying and researching is now in the possession of the Dickinson College Archives in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In this blog post, I will go in-depth about who used this book and how it came to be a part of Dickinson’s Archives collection. I have written two prior blogs about the history and composition of this book that I would recommend reading along with this one (blog post 1 and blog post 2)!

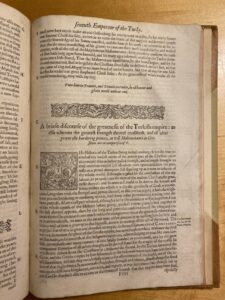

French Cookery: The Modern Cook was primarily used by upper-middle-class families; this was Francatelli’s intention. On the title page of the book, he specified it was “adapted, as well for the largest establishments as for the use of private families” (See Figure 1). The title page tells us that this book was meant for familial and restaurant use; however, it isn’t clear which class of people it was meant for. The actual recipes had to be examined to be able to answer, “Who used this book?” Each recipe is of very high quality and includes expensive ingredients. Bishop uses a great example of the recipes for Lamb’s ears (Bishop, 2018). This book includes three separate recipes, all with expensive ingredients such as a full lamb, cayenne, parmesan, and veal. Because the ingredients used were difficult to obtain, those making these recipes needed the money and resources to access them. As I discussed in my previous post, Francatelli’s next two cookbooks were marketed toward lower-class families and the staff of the upper class. The intended purpose of those books was indicated in their titles: A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Class (1852) and The Cooks Guide and Housekeepers and Butlers Assistants (1861). His fourth cookbook was for confectionary foods and wasn’t marketed for a specific class of people. This book reached its intended audience; the recipes weren’t accessible to lower-class people as they couldn’t afford the ingredients.

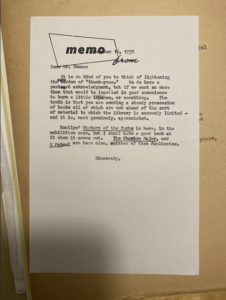

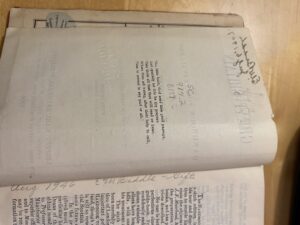

This specific copy of French Cookery: The Modern Cook, had at least two owners. This book was donated to Dickinson College only five years after its publication; the first owner was Mrs. B. Stilingfleck. This name was an approximation by the Dickinson College archivists; her signature was included on the title page (see Figure 1). The signature has faded a bit, and there is an ink bleed over the last name. There was no information on her in the Dickinson College records or online. A few dogeared pages in the cookbook tell us this cookbook was used, including a traditional filet recipe and a tapioca pudding recipe (more information about this is in my first blog post, linked above). The second known owner was William Armstrong Graham. His name is on the gift plate inside the cover; he donated the book in 1851(see Figure 2). He was an alum of Dickinson College, class of 1844, and went on to study at the Princeton Theological School, eventually becoming a member of the clergy of the Presbyterian church (I found this information through the help of the archivists and “House Divided,” a Dickinson College resource about the civil war). Dickinson College at this time had two societies that were dedicated to conversations around literature, as well as gathering books (a lot of the material that makes up the Archives currently). Graham donated this copy to the Union Philosophical Society. John Fletcher Hurst, class of 1854, accepted this book into the Union Philosophical Society’s collection. Hurst, a member of the Union Philosophical Society, went to work in law for a while after graduation but ultimately became a Methodist Bishop and became the Bishop of Washington, DC. He is most notable for founding American University in Washington, DC (House Divided). I asked the archivists if there was any more information about Graham’s donation or if there was a record of more donations from him. Unfortunately, due to a fire in 1904 that burned down Denny Hall (an academic building at Dickinson College), most of the records from the Union Philosophical Society were lost; Denny Hall was where they stored all their records. Due to these two snafus, there is no information about Graham’s relation to the Union Philosophical Society or any other potential donations he may have given them.

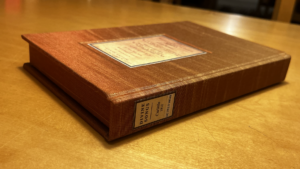

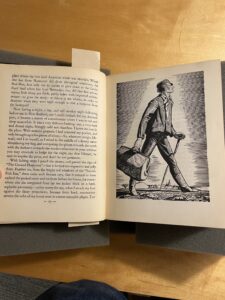

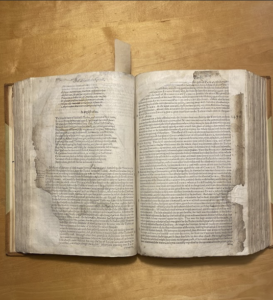

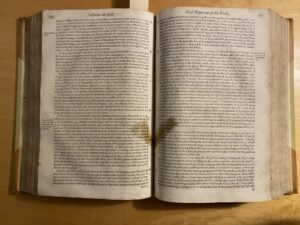

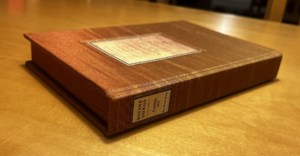

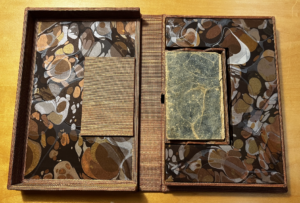

The Archivists of Dickinson College who helped me examine this copy of French Cookery: The Modern Cook didn’t notice any repairs to this book. It doesn’t look like the book has been rebound. Seemingly, this is the original binding because of the broken binding (see Figure 3) and the gold-etched illustrations on the cover and spine that match the illustrations in the book (see Figures 3 and 4). As for repairs, all of the pages look consistent with one another, and none of them look as if they’ve been altered since their printing. The book was in a good enough condition when donated to not need repairs. Even now, the book is still in pretty good condition; it is separating from the spine, but all the pages are still readable with no significant damage (see Figure 5).

There are some unanswered questions about this copy of French Cookery: The Modern Cook. It is nearly impossible to know for sure who had the book after Mrs. B. Stilingfleck and how William Armstrong Graham came to have it. We also do not know if this book was a part of multiple donations from Graham or if this was a stand-alone donation. I don’t know for sure that this copy didn’t go through repairs of any kind. Despite all that I don’t know about this book, I have learned a lot through the limited resources I’ve had access to. The Archivists have given me resources and rich information about the production, afterlife, and history of French Cookery: the Modern Cook.

Works Cited

Bishop, Amy. “The Booker T. Washington-W.E.B. Du Bois Debate.” Cardinal Tales Highlights from 2018, Iowa State University Digital Press, 7 July 2021, iastate.pressbooks.pub/cardinaltales1/chapter/rare-book-highlights-.

“Graham, William Armstrong,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/5768.Susan, and Susan. “Charles Elmé Francatelli, Maitre d’hôtel and Chief Cook in Ordinary to Queen Victoria.” Unofficial Royalty, 9 Aug. 2024, www.unofficialroyalty.com/charles-elme-francatelli/.

“Hurst, John Fletcher,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, https://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/5951.

Remillard, Lynne. Union Philosophical Society, chronicles.dickinson.edu/studentwork/1934/social/unionphilsociety.html. Accessed 29 Nov. 2024.

Susan, and Susan. “Charles Elmé Francatelli, Maitre d’hôtel and Chief Cook in Ordinary to Queen Victoria.” Unofficial Royalty, 9 Aug. 2024, www.unofficialroyalty.com/charles-elme-francatelli/.

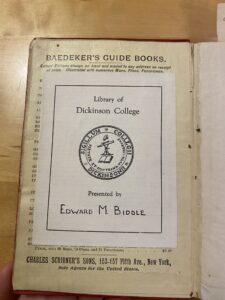

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first

There is also an article on Edward M. Biddle in the file, written for The Dickinson Alumnus. According to this excerpt, his father was E.W. Biddle, a Judge and former president of the Dickinson Board of Trustees. Edward M. became a legal adviser and was an active member of his community. The most important part of this excerpt reads: “As a traveler he has been in Europe a number of times, has visited South America, as well as extended regions of the United States.” This of course indicates a possible use or ownership of this Baedeker’s guidebook, a fact exacerbated by its publication in 1906, soon after his graduation from Yale. This largely eliminates the possibility of the first  inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

inscription in the guidebook being “E.W. Biddle” as opposed to the initially-assumed “E.M. Biddle”… except that E.W. was alive until 1931, when he died unexpectedly at 79. According to the Dickinson College Archives, E.W. was practicing law until 1895, at which point he became the president judge in the Cumberland County Court of Common Pleas. I have already noted the condition of my copy of Baedeker’s Great Britain – it has no annotations or inscriptions within it beyond the two at the beginning of the book, and there is very little wear beyond aging. The only clear indication of use is the broken bookmark, which could be because of age but also because of repetitive use. It is entirely possible to consider that E.W. purchased this book as a way to experience some form of travel from the comfort of his home. He also could have purchased the book as a gift for his son E.M. for graduating from Yale, which he did in 1906, and we know that he travelled. Uncertainty abounds.

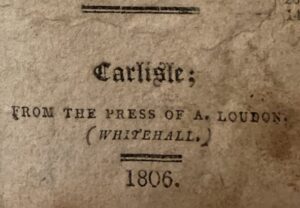

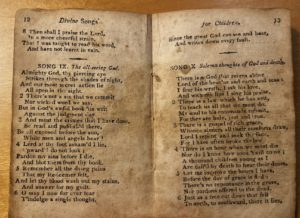

and bled. It very likely is a signature or a name and a date. The book is twenty-nine pages in total, including the copyright page. The Ten Commandments, “put into a short rhyme” follow the final hymn. The book ends with a summary of the commandments, “With all thy soul love God above, And as thyself thy neighbor love,” and “FINIS

and bled. It very likely is a signature or a name and a date. The book is twenty-nine pages in total, including the copyright page. The Ten Commandments, “put into a short rhyme” follow the final hymn. The book ends with a summary of the commandments, “With all thy soul love God above, And as thyself thy neighbor love,” and “FINIS

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from