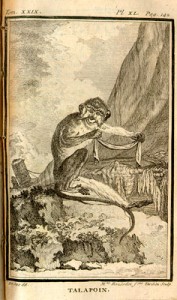

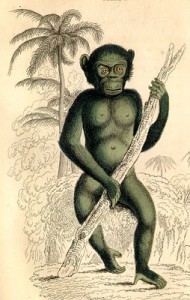

Depictions of monkey’s and apes in natural histories by Buffon , Jardine, Goldsmith (and others) led to confusion and anxiety on the part of natural historians and the general public. Long before Darwin and Mendel, similarities between simians and humans were as unsettling as they were hard to explain. The problem was not merely anatomical; the sagacity of apes made it clear to early naturalists that these creatures could reason and communicate. Ironically, most varieties of higher primates were often depicted in ways that enhanced their similarities to humans. The orang-utan was referred to as homo sylvestris (“man of the woods”) well into the nineteenth century. In addition, comparative anatomy suggested only minor differences among beings (monkeys, apes and homo sapiens) who were supposed to be a far apart on the hierarchical “Great Chain of Being.” Nonscientists could see monkeys and apes in close proximity once zoos began to exhibit them and taxidermied specimens began to appear in natural history museums in the second half of the 18th century. By the time of the famous mid 19th-century cartoon depicting Darwin with an ape’s body, anxiety about our relation to “lower” forms of life had reached epidemic proportions.