Mia Jones | Leah Keys | Sophy Nie | Lily Swain

Making a Country More Accessible

One text in particular has been relevant to my time here in France and I often find myself thinking about it: The book titled Beasts of Burden: animal and disability liberation by disabled activist Sunara Taylor, where she discusses the interaction between animal rights and disability. This book encouraged me to reflect on the way ableism is expressed in the US not only through infrastructure and social consciousness, but how exclusive public spaces, institutions, and cultural spaces are in the US.

So, before my stay in France, due to the spaces I was in, I’d only read about the way public spaces could be improved to be more inclusive but never actually witnessed the support in place. That was until I arrived in France. Within 3 days of being here, I’ve noticed that the public space is shared amongst people with different levels of ability; on the street, in cultural and educational institutions, and on public transportation services, the city of Toulouse is a lot more accessible than any place I have personally seen in the US.

How did France become accessible? Are they more socially accepting? These are questions that arise in my mind as I observe the way the city and people interact and respond to each other.

The disability act of 11 February 2005 is part of the reason why Toulouse is somewhat accessible today. This ensures the right to work is extended to those with disabilities. It also mandates that public housing and infrastructure should be and continue to be accessible for all individuals of varying levels of mobility or ability (citation). This law has been influenced by many historical events, dating back to the French Revolution, all of which have shaped the policy of disability in France.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was established in 1990 and functions similarly to the disability act in France, Both aim to guarantee equal rights and opportunities for individuals with disabilities. The ADA prohibits discrimination across various spheres of public life employment, education, transportation, and both public and private spaces accessible to the public. Despite the similar purposes, I don’t feel the act was carried out similarly or effectively in the US. Certainly, here’s the addition to reflect your opinion and acknowledge the potential factors influencing your perspective: my perception might be influenced by my tendency to visit mostly able-bodied spaces or a lack of awareness. The effectiveness of these acts may differ due to various factors. I recognize that it might not reflect the complete reality, or I might be right.

To understand the French point of view, I feel there are more questions and conversations that I need to have with different people during my stay here. Even though Toulouse may appear to be more integrative with different body types and other abilities, it made me conscious about the spaces I’m in and how able body privilege presents itself in the US.

Accessibility and Public Transportation

I’ve only lived in Toulouse for a few months, but already I’ve noticed multiple examples of accommodations for people who are disabled. The public transportation agency Tisséo stands out as being particularly aware of inclusivity and working towards building a better environment for all (Accessibilité. Tisséo Collectivités, s.d.). Take, for example, the bus. There are ramps that can descend to allow people in wheelchairs to easily board the bus and then within, there is space specifically marked for wheelchairs that have bars to hold onto and padding against which to rest your knees. In addition, there are signs to remind people to leave the seats for those who need them more than they do, and each stop is announced by voice and in writing to ensure that the greatest number of people can understand.

There’s a lot of conversation around the inclusivity of the metro.

Tisséo is currently undertaking an extensive project and is adding a new metro line through the city. With this construction, there’s a lot of conversation around the inclusivity of the metro. As I take it to class every day, I’ve had time to form my own thoughts on this matter. From what I’ve seen, there seems to be an escalator present at every metro station, however that doesn’t always mean an escalator in each direction. Sometimes, there are stairs to descend with the option of an escalator to go back up. So, those who have difficulty with or cannot take the stairs at all will have a hard time getting to the track. There is typically an elevator as well, but there is never more than one. At Jean Jaures (the busiest station where the two metro lines cross) there is often a line of parents with strollers waiting outside the elevator. Evidently, this adds complication for those who rely on the elevator.

Not all disabilities are visible, but the culture at least opens a space for discussion and for willingness to improve the infrastructure.

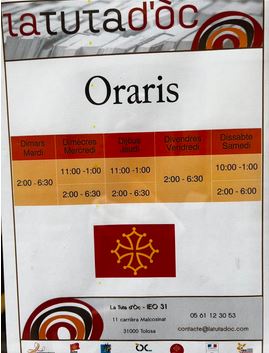

During my commute, I often see advertisements for “allô Tisséo”, a service in the case of urgent questions. It’s presented as an easy way to get immediate help, however the services for those who are deaf or hard of hearing only operate during reduced hours. These services are only offered from 9am to 5:30pm Monday through Friday, contrary to the advertised hours of 6am to 8pm during the week with reduced hours on Saturday (Aide & Contact | Tisséo, s. d.). Additionally, public transportation is built to allow the greatest number of people to travel at once, meaning that the number of seats is significantly less than the amount of standing room. However, respect is an important part of the culture and people are quick to offer their seats to those that they think may need it more than them. Not all disabilities are visible, but the culture at least opens a space for discussion and for willingness to improve the infrastructure.

In 2008, Tisséo created the Commission d’Accessibilité de Réseau Urbain to open communication with associations representing the disabled community. This past summer, they organized thirteen workshops to prioritize the experience of disabled travelers (Accessibilité, s. d.). and to try to build the C line in the most inclusive manner possible. Based on these workshops, Tisséo has announced that they will continue making announcements at both the audio and written level, as well as continuing to include a picture with every metro stop to make the recognition of each station easier. Furthermore, agents will continue to take sign language courses and drivers will be educated on the topic of disability. Through this, Tisséo agents will be better able to recognize differences and adapt to help each person in the way that best suits them. It is important to note that my observations come from the perspective of a non-disabled person; I can only speak to my own experience and what I have noticed. In my opinion, the public transportation in Toulouse seems fairly accessible. It is by no means perfect, but there is a willingness to communicate with the disabled community and implement changes that will facilitate the travel of all people.

Accessibility in Public Spaces

Public transport is a public space where accessibility is very important and visible. With that said, there is another type of public space that is less discussed in terms of accessibility: cultural spaces. France is a cultural heritage haven for art history enthusiasts like me. In mid-October, I took a day trip to the famous medieval town of Carcassone, where I spent 2 hours walking the rampart under the hot sun, climbing up and down spiral staircases and towers, admiring all the medieval fortifications. Later, a giant tactile book by the entrance of the giftshop caught my eye. It was part of a collection designed to allow visually impaired people to experience the great cultural sites of the country. The book sparked my interest in a question that is crucial but rarely discussed gradually rose in my head: how do people with disabilities in France access cultural sites, and share the same enjoyment that I share?

How do people with disabilities in France access cultural sites, and share the same enjoyment that I share?

The question seems multifaceted and has a lot to unpack. My thought immediately goes to different types of disabilities, including vision impairment, being deaf or hard of hearing, mental health conditions, intellectual disability, and physical disability, that cultural spaces try to accommodate. Museums in Toulouse, such as Le Musée des Augustins, have elevators that provide access for the public with mobile and visual disabilities. Le Musée des Augustins also has a newly developed multi-sensorial route, where the visitors discover certain art pieces and points of interest through touch and listening. The other museums I’ve been to have some of their interpretive texts translated into Braille. Carcassonne, a tourist site with the “Tourism & Handicap” label, also provides a personal listening system for the hearing impaired and a magnetic collar for MP3. Similar methods exist in American museums to varying degrees. Some museums, like the Cincinnati Museum Center, are ahead of others. Aside from the systems we discussed in France, the museum has quiet areas with earmuffs, weighted blankets, and other items that visitors can borrow when they need them. It also offers a sensory map which indicates the different sensory levels in the museum. As in the United States, cultural attractions in France are moving to be more accessible. But is it enough?

As in the United States, cultural attractions in France are moving to be more accessible.

While conversing with Emma, our French-American point of reference, she suggests that there are still questions unsolved on a larger scale. Research shows that only 18 % of French museums today have the “Tourism & Handicap” label proposed by the state as of 2018. Many of France’s old patrimonial sites are still not fully open to people with disabilities. Access becomes difficult in museums located in historic, cobble-stone neighborhoods. Many historical monuments have difficulty welcoming people with disabilities also due to the structure of the architecture themselves. Additionally, non-physical disabilities like intellectual disability are even more likely to be ignored, as my host Françoise, a teacher of students with disabilities, rightly suggested to me. More difficulty, however, comes from the overarching issue of cultural organizations. No budget line was created when the Equal Rights and Opportunity, Education and Citizenship for Individuals with Disabilities Act was enacted in France in 2005. In turn, non-profit cultural institutions had to use their own resources to tackle these questions and are limited from drastic reforms due to financial restrictions and lack of personnel. In the article, a mediator admits that he can only devote 10% of his time to the issue of disabled people.

Heritage plays a crucial role in French culture and identity. However, even though France has excelled in making cultural spaces more accessible to a wider group of people, such as the unemployed and the youth, their work to accommodate people with disabilities still requires effort and discussion. However, France is not alone in this problem. Many American museums also lack the funds and personnel that should be dedicated to this subject, reflecting a broader trend in the global museum world. Even though museums are public institutions designed to be accessible and inclusive, they still carry an air of prestige with them. Therefore, it is extremely important to demystify museums and invite people with disabilities into these spaces, so that museums can truly fulfill their functions.

Do Accomodations Really Accommodate Students with Disabilities?

For those who have been through their first year of college or university, it’s not hard to remember the feelings fear, uncertainty, and like you don’t fit in. These reactions apply to all students; however, they are even more pronounced amongst students with disabilities. In addition to the typical worries of new students, students with disabilities have to think about how to navigate the campus if they have a physical disability, or how to hear their lectures if they are deaf. Students with less visible disabilities, like mental illnesses, dyslexia, etc. are also included under the umbrella of students who have the right to feel at ease during their college transition and during their entire college experience.

Thus, it makes sense that colleges and universities should make accommodations for students with disabilities. In fact, it’s the law. In France, the law of February 11, 2005 protects “equal rights and opportunities, participation and citizenship,” according to the website of the Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche. This law includes people with mental disabilities (difficulty with reflection and conceptualization), cognitive disabilities (problems with memory and attention), mental illnesses, and people with multiple disabilities, in addition to physical disabilities. So how do French universities proactively strive towards equality on their campuses?

One can look to the example of the Université de Toulouse Jean-Jaurès (UT2J) in Toulouse, France. According to an article published by UT2J in 2022, the number of students with disabilities enrolled at the university grows each year. During the 2021-2022 schoolyear, about 5% of all students had a recorded disability. To put that number in a little more context, the percentage of Dickinson College students who have a known disability is 20%; and 75% of this group receives academic accommodations.

Going back to UT2J, there are several accommodations that I’ve observed during my time there. First, there are raised lines that run all the way down the middle of the university sidewalks. People who are visually-impaired or blind can follow these lines with their canes from one building to another, or even from the campus to the metro station. But the lines don’t continue inside of the campus buildings, which could get in the way of easy access to classrooms. Additionally, for people who are visually-impaired, UT2J provides audio versions of its books and has audio versions of certain classes available online.

In the U.S., an exchange like that would never take place in public.

While in one of my classes, I noticed that there was an interpreter translating the professor’s lecture into sign language. What I found interesting was that the professor asked, in front of the entire class of 300 people, exactly who the deaf person was so the interpreter could know in what direction to sign. In the U.S., an exchange like that would never take place in public due to HIPPA, the law that protects personal medical information from being shared publicly. On this subject I also wanted to note that having a sign language interpreter is not a perfect solution; the 2 hour class had to have a pause in the middle because it was tiring for the interpreter to sign with her hands for so long. In addition, for students who are hard of hearing or deaf, other accommodations like sound translation apps or note-takers exist. UT2J also has in place accommodations for people with mental, cognitive, or mental illness-related disabilities. Pertaining to exams, the university’s website explains that “individual meetings, increased time, and explanations of instructions” are options to support equal chances for these students to succeed.

It appears that UT2J tries to accommodate its students with disabilities as well as it possibly can. However, could the university do more? It’s difficult to know the extent to which the university actually follows and implements its own guidelines, especially when I’m not personally a student with a disability. I don’t want to speak for these students or to give false impressions of their situation; I am presenting here only my own observations and inferences about how the university’s accommodations affect them.

Now, let’s cross the Atlantic Ocean to look at how accommodations for students with disabilities exist in the U.S.. Dickinson College, a place I know well, is a good candidate for comparison. Looking at accommodations for students with physical handicaps, Dickinson tries its best to provide buildings that are accessible with elevators and ramps. But there are certain dorms and residence buildings without elevators, which would make it difficult or impossible for people with limited mobility to live there. And there are no raised lines on the sidewalks to help visually impaired people at Dickinson like there are at Jean-Jaurès. However, I do remember that during my first year at Dickinson, a voice feature was added to the college’s crosswalks so that visually-impaired students could better navigate campus.

Considering Dickinson’s academic accommodations, there is an Office of Access and Disability Services where students can go for advice and to apply for certain types of help. For example, according to Dickinson’s website, extra time on tests, note-takers, and certain technologies for visually-impaired or deaf students are possible aids. But I also realize that there are obstacles for Dickinson students trying to receive accommodations, and consequently students often feel frustrated with the system. When applying for accommodations you have to provide proof of ADHD, anxiety, chronic illness, etc. to create a 504 plan with the college; these forms and processes (which often require seeing a doctor) take time. All in all, Dickinson’s “American-style” system of accommodations isn’t perfect either.

From my point of view, students with disabilities in both countries face challenges despite the existence of accommodations.

From my point of view, students with disabilities in both countries face challenges despite the existence of accommodations. Luckily though, the current social climate has favored an increasing visibility of people with disabilities and their needs, mostly thanks to disabled peoples’ defense of their own rights. This is especially evident in the creation and growth of the Disability Studies field in the U.S.. People with disabilities deserve equal chances; in today’s world, there is hope that such equality will come to fruition.