Here are links to examples of Urbanatural Roosting in an urban Context. These links are organized by city, with the map moving from the Northeast Coast of the United States to the Southwest Coast. (We will be adding international cities as soon as possible.)

New York

THE HIGH LINE:

THE HIGH LINE (a.k.a. The High Line Park) is one of the most interesting urbanatural sites of recent years, particularly in New York City. The residents of NYC have taken an old, abandoned elevated railway line and converted it into a gorgeous, functional, almost wild park in the middle of the most “urban” city on America’s East Coast. The HIGH LINE functions like a walk through the wild woods or forest fields that just happens to exist in the middle of Manhattan Island, running from to Chelsea to 30th St. West. In 1999, Joshua David and Robert Hammond–two local residents, began to support the idea that a then-decaying rail line–on which a final train of frozen turkeys (three boxcars worth) had run in 1980–should be saved. Two decades earlier, when the route fell silent, many residents wanted to tear the rusting eyesore down; but–at that time–Peter Obletz, who lived in Chelsea at the line’s southern end–argued in court that demolition would be a local, historical, and wasteful mistake. Then, in 2002-03, their group–“Friends of the High Line”–established the financial feasibility of saving this unique urban treasure, and they announced a competitive “Designing the High Line” project. CSX Transportation then donated the land to the city, and James Corner Field Operations, a landscape architecture firm, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf, planting designer, were selected to begin work on the project.

The High Line Gets “Built”

By September of 2014 the project was finished, and Friends of the High Line enthusiastically acknowledged their decade-and-a-half of dedicated work on the entire project, reaching from Gansevoort Street (the Meatpacking District) to West 30th Street further uptown. The supporters currently claim that this almost perfect example of urbanatural roosting draws in more curious sight-seers and visitors than Lady Liberty on her own island to the south of Manhattan. There are currently over 300 plants that are watered and pruned on the High Line, and treated very well here: grass varieties, perennial flowers, shrubs of many sizes, and even a number of tree species that will provide increasingly more shade as the years–and the decades–progress. The High Line is not going anywhere–it will hopefully serve as a model for many such sites in cities throughout North America and, let us hope, the world. No one is allowed on the High Line except walkers and, like its model, the Coule Verte in Paris, the one-and-a-half (1.5) mile–2.4-kilometers–pedestrian pathway offers gorgeous views of the East River and the Hudson River, as well as glimpses of countless interesting buildings on both sides and the streets below; it often links neighborhoods of the city faster than if hikers had taken taxis or their own cars (God forbid such motorized vehicles in a city that rarely needs them: maybe for getting a woman in childbirth to the hospital?). Its West Side vantage point reveals yet another way that downtown features are reclaimable, and that industrial architecture is much more than just recyclable metals.

Sites connected with The High Line:

The High Line Hotel: As The New Yorker tells us–in its 9/22/2014 issue–this Gothic masterpiece “inhabits the former General Theological Seminary, in Chelsea. One late-summer evening, patrons in designer sunglasses lazed beneath gas lamps, slurping oysters and sipping Chandon Brut, or Étoile Brut, or an eight-hundred-and-fifty-dollar magnum of Dom Perignon Vintage Blanc ’04 from large coups.” This hotel was a perfect adaptive reuse–as we used to say in my days at The National Trust for Historic Preservation–of an outmoded theological seminary. It overlooks a beautiful part of the city and is situated so that you can walk the full length of the High Line, up and back, without any effort beyond enjoying all of the growing plants and happy people you encounter. The first time I walked the full circuit, up and back, I saw more smiling New Yorkers that I had ever seen in one place at one time–ever! Urbandaddy.com gives us the details for what they call “the most pleasant outdoor drinking spot in New York” at this fabulous venue: Champagne Charlie’s at The High Line Hotel, 180 10th Ave (between 20th and 21st) New York, NY 10011. 212-929-3888. What could be more urbanatural than that!

BATTERY PARK CITY:

Battery Park City, a reclaimed and urbanaturally designed neighborhood on the southwest side of Manhattan, was completely developed from land excavated during the building of the first World Trade Center Towers (and several other projects), as well as sand dredged out of the New York harbor, in the 1970s. The area was damaged during the 9/11 terrorist attacks but has since emerged as one of the most dynamic areas of Lower Manhattan. It includes 92 acres acres, over one third of which is preserved as natural parkland. Development of the area followed a new model of urban planning, allowing for 36 acres of total open space along with residential development covering 7.2 million square-feet and commercial buildings adding an additional 92 million square feet. The residential buildings include The Solaire, which calls itself “America’s first environmentally advanced residential rental tower.” A LEED Gold structure, it was also the first of New York’s high-rise residential spaces certified by the U. S. Green Building Council: computerized electronics manage the environmental impact of the building, it employs photovoltaic cells for the production of electricity and generates 67 % lower peak energy demand that New York’s building codes require.

Central Park:

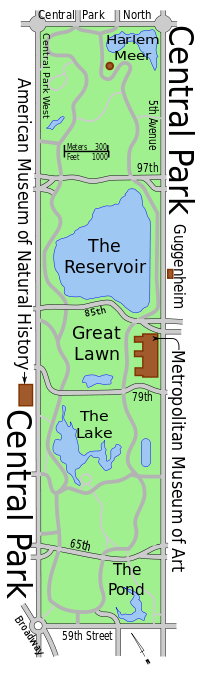

Contemporary Map of Central Park

Central Park is the most frequently visited urban park space in America. While not one of the largest parks in America in terms of land area, it is nevertheless one of the most well known, most often filmed, and most widely beloved among New York City dwellers and visitors over the past two centuries. The winning plan for the park was an original design–“The Greensward Plan”–by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux: “a democratic development of the highest significance,” according to Olmstead, that included 36 distinctly designed bridges, double lines of elm trees leading to the Bethesda Fountain Terrace, and a dramatic combination of woodlands, lakes, paths, and cross-park carriage and automotive traffic routes (as well hidden as possible from the view of the nature-loving public). From the 1875 map (above) to the contemporary north-south view of its well-known features (left), Central Park has served as a a quiet retreat, a perfect lunch spot, a hiker’s venue, and a romantic meeting place for decades. From its original 778 acres in 1857–the year it was founded–to its current 843 acres, the Park has been central in many respects (geographically, psychologically, and romantically) in the minds of most New Yorkers.

Surprising features inside of the park include: Cleopatra’s Needle (c. 180 tons and 70-feet-tall), an ancient Egyptian obelisk created around 1450 BCE for Pharoah Thutmose III. Two centuries later its hieroglyphic inscriptions honored Rameses II; Strawberry Fields, 2.5 acres set aside and inscribed with the single word “Imagine” to honor John Lennon, former Beatle gunned down by an assassin five years earlier at the Dakota Apartment Building close by on Central Park West; and finally, Belvedere Castle, a Victorian Folly that was a late (1880) addition to the Park by Olmstead and Vaux: the castle now serves as the Park’s official weather station and has also appeared in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters, as well as in Sesame Street–where it served as the home of Count von Count (above). Below is a view well-known and beloved by New Yorkers, Central Park taken from high above Central Park South, legendary street that runs from Columbus Circle in the west to the Plaza Hotel in the east, home of Eloise in the classic children’s book, and site of the legendary Palm Court and Oak Bar eatery and drinkery.

Urban Hawks:

One of the most obviously urbanatural activities in Manhattan, and also one of those most closely linked to roosting, is UrbanHawks, a group of committed avian naturalists and birders (folks the British often refer to as “twitchers”) who devote countless hours of their time to tracking, recording, and documenting (usually with cameras and videocameras) the raptors of New York City: that is, the hawks, owls, and eagles that populate or pass through eastern North America’s largest urban space. Their website chronicles an amazing series of images and short films of these remarkable creatures as they fly, roost, mate, feed, raise their young, and generally go about the business of living. See, for example:

See the YouTube above for a remarkable video example of the sorts of work done and posted on the UrbanHawks website. These raptor enthusiasts have produced a wonderful archive that will be of use to naturalists and scientists as well as bird watchers and hobbyists.

Hidden Urbanatural Spaces, Parks, and Gardens in NYC

Link to this site–(HIDDEN)–if you are interested in often not well known elements of urbanature throughout the five boroughs. This webpage chronicles a remarkable list of generally overlooked urban treasures of natural beauty, historical significance, ongoing practical function, or a combination of the three. Here are some of the most remarkable sites:

—Queensway: the next possible High Line, Queensway is a 3.5 mile long section of elevated rail line (part of the old Long Island Railroad [LIRR] Rockaway Beach Branch) that has been completely abandoned since long ago 1962. Friends of the QueensWay now would now like to embody the best urbanatural principles to convert this stretch of urban blight into a beautiful and useful park, a new element of the Borough of Queens that will exist for the benefit of residents and visitors of many stripes: hikers, bikers, joggers, walkers and perhaps even botanists, gardeners, and urban foresters. Current visitors–who can find there way in–can already wander through dense underbrush and occasional fauna or clamber around rusting rail lines, overpass bridges, and industrial flora.

—The Elevated Acre: an acre-long piazza connected to 55 Water Street, this clever bit or urbanatural design took an otherwise unused space and transformed it into one of the cleverest of contemporary urban designs. Walkers on the nearby sidewalks beneath the park are drawn by lights, plantings, stairs, and shiny escalators to find out what awaits them one story up above the traffic noise and bustle. Once there, visitors find comfortable bench seating with dramatic views of New York Harbor in one direction and the Brooklyn Bridge in another. This magical acre also offers space that can be used for parties or receptions as well as accommodating an outdoor amphitheater, and even an ice-rick. This small park is part of the long-term project known as the Green Necklace, a series of open and natural spaces that will eventually encircle Manhattan’s edge.

—Staten Island Greenbelt: Having been called “the Adirondacks of the five boroughs,” this area of distinct parks, extensive hiking trails (35 miles in all), and acres upon acres of open space (totaling 2,800) serves Staten Island and the wider metropolitan area as a rich resources of natural, educational, and entertainment facilities. In the High Rock Park, for example, visitors may be able to find some of the quietest and tranquil woods in the entirety of New York City. A native plant center, golf course, recreation center, carousel, and nature center, are just some of the treasured features of this well planned and well supported region. The greenbelt is wild enough to support not only the desires of its human visitors but also the lives of creatures ranging from white-tailed deer, cottontail rabbits, and eastern chipmunks to snapping turtles, American bullfrogs, and even the occasional eastern milksnake.

—The Wycoff House Farm Museum: Who would have thought that there would be a complete farm museum almost in the middle of Brooklyn? One of the oldest houses–if not the oldest houses in the city, the Pieter Claesen Wycoff House is a National Historic Landmark, parts of which were standing on its current location in 1652. The museum now operates a functioning garden–growing everything from berries and herbs to a wide variety of vegetables, and eventually even an apple orchard. At the same time, the museum’s primary function is educational; it sets out to documents farm life in the 17th-century and beyond, while also working to demonstrate as many material elements of that life as possible. As the garden’s website notes, “the hope is that the Garden’s most enduring product will be an educated community.”

—The Creative Little Garden: voted the Best Community Garden by the Daily News in May of 2012, this neighborhood green-space was the result of a great idea. Instead of having separate gardening plots for individuals or small groups, the entire if small space (24 x 100 feet) is gardened by the entire if small community of 40 to 80 local residents. The garden is open, however, to all visitors or passersby as a place to sit down, enjoy a rest, and even bring your leashed pet for a few moments of quiet in the often less-than-quiet city, even in the East Village. The Creative Little Garden is located at 520 East Sixth Street, between Avenues A & B. Enjoy! –Ashton Nichols

Boston

Boston Common, here you are at the oldest urban park in America. Here are 50 acres in city-center that served as the spot for “until-you-are-dead” hangings–always in public–until 1817 (not so long ago, really, when you think about it), and had cattle and other edible critters grazing there until at least 1830 (who kept these records!?). Now, the City Fathers say that The Common–as it is usually known–is at the center of an urbanatural feature called “The Emerald Necklace,” a circuit of green-spaces that snake their way through some of the finest of neighborhoods of Beantown. All the greats have spoken here to cheering crowds: John Paul II, Gloria Steinem, and Martin Luther King, who said told a crown here that Boston’s schools had to fully desegregate, just before he told the Massachusetts State Legislature the same message later the same day; the message did not seem to work up there in the North, at least not for a long, long time. In any case, Boston Common may be the best urban park in America, unless you live in Manhattan and have that Frederick Law Olmstead masterpiece called central Park outside of your front door.

Approximately 100 years ago Frederick Law Olmsted, America’s initial landscape architect, (Olmsted) envisioned a place where humans could connect with nature. Today, the ‘Emerald Necklace’ that stretches around seven miles, covering land from Back Bay to Dorchester in Massachusetts, does just that. Run by the Emerald Necklace Conservancy, this large park system is home to over one millions tourists and visitors each year, the Franklin Park Zoo, the Arnold Arboretum, sports fields, a golf course, and many other attractions (Em Neck Cons). The Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University was established in 1872, serving as the first public National Arboretum in the nation. The arboretum covers nearly 300 miles and contains over 15,000 plants of over 4,000 different species (arboretum). There are several highlighted attractions including the Bussey Brook Meadow, Hemlock Hill, the Maple Collection, and Rhododendron Dill, among others.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia Initiatives

In 2009, Mayor Michael A. Nutter released the Philadelphia Greenworks initiative, with a goal of creating a more environmentally conscious community. The six-year plan, created with the intention of making Philadelphia the “Greenest City in America” (Phila Gov), focused around several target achievements. Some of these included lowering the city government energy consumption by thirty percent, reduce greenhouse gas emissions by twenty percent, and reduce vehicle miles traveled by ten percent (Phila Gov).

The Morris Arboretum, located on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, was established in part to inform citizens about the relationship between the environment and society. In doing this, they also encourage harmonious interactions between these two elements of our culture. The building that is now the arboretum was once known as Comtpon and served as the summer home for siblings John and Lydia Morris, whose father founded the I.P. Morris Company (Morris).

The Morris Arboretum mission statement declares, “Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania is a historic public garden and educational institution. It promotes an understanding of the relationship between plants, people and place through programs that integrate science, art and the humanities” (Morris Arboretum). Within the arboretum are approximately 12,000 plants, trees native to a plethora of countries spanning several continents, over twenty gardens, and habitats containing various species of birds, among other attractions.

In 1792, Pennsylvania Quaker John Bartram purchased a extensive 102 acres of land from Swedish settlers (Bartram). Shortly thereafter he began collecting a wide variety of plant species. The site of the garden was continuously tended by various relatives and colleagues until 1891, when Philadelphia took ownership of the land (Bartram). In 1893, the John Bartram Association was founded and began managing what is know recognized as Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia. Bartram’s son, William was the naturalist traveler who authoredTravels through North & South Carolina, East & West Florida, etc., now known as Bartram’s Travels, a work that had a power influence on the English Romantic writers Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, and Shelley, among others, in their early images of the American landscape, flora and fauna. Today, the 18th-century style garden that his father began still covers 45 acres of land situated along the Schuylkill River, just outside downtown Philadelphia.

Baltimore

The Inner Harbor:

Who would have imagined that one of the world’s largest estuaries–Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay–could extend all the way into the literal heart of a major city of over one million people–bringing with it oysters, blue crabs, and many of the plant and animal species that characterize this wonderful source of food, recreation, and perhaps most of all examples of estuarine natural beauty that are hard to rival anywhere. As an example of urbanature, the Bay is a remarkable instance of humans living, or trying to live, in harmony with a rich natural environment that intersects with the lives of these people both literally (there are over 100,00 streams and 11,000 miles of shoreline) and figuratively (the culture of the Bay is four centuries old and filled with unique linguistic, artistic, and environmental ways of living). The Chesapeake Bay extends north from its mouth at the end of the Delmarva Peninsula all the way to its most northern major tributary, Maryland’s Patapsico River. Along the way it provides numerous economic opportunities in addition to its recreational and environmental benefits.

A 2009 report by NOAA (The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) reveals “that the commercial seafood industry in Maryland and Virginia contributed $3.39 billion in sales, $890 million in income, and almost 34,000 jobs to the local economy.” Of this impact, oysters represent the environmentally sad part of the story, since their current catch represents fewer than one percent of historic catches. Meanwhile, blue crabs tell a different tale in recent years, primarily because of carful management of the female population of the stock:

“According to the 2015 Chesapeake Bay Blue Crab Advisory Report, released by the Chesapeake Bay Stock Assessment Committee (CBSAC), the start of the 2015 crabbing season saw 101 million adult female blue crabs in the Bay. This marks a 47 percent increase from last year’s abundance of adult females, which the Chesapeake Bay Program tracks as an indicator of Bay health. Because blue crab abundance is above the 70 million threshold, the blue crab stock is not considered depleted. And because just 17 percent of adult females were harvested in 2014—well below the 25.5 percent target—overfishing is not occurring.” (CBP)

Washington D.C.

Monuments & Memorials in Washington, D.C.:

Probably no city in America has the combined monumental and federal qualities of European cities like Paris, Vienna, or Rome, but Washington, D. C., comes very close; although many cite the precise details incorrectly, there is an absolute limit on building height in our capital city. No structure in the U. S. capital–after the 1890s–could be taller than “the width of the adjacent street plus 20 feet.” So, this law is not about the height of the Washington Monument or the statue on top of the Capitol Building, but it does restrict building heights to make the city more like Paris or those other beautiful, boulevard-crossed, monumental capitals of Europe and South America. That idea is not quite urbanature, but it does prepare the way for a city of wide boulevards, open spaces, and parks that line the Potomac River and surround the many of the most classically-inspired buildings in America.

The National Mall

Once in our federal city, head first to The Mall, a long open-greenspace that connects the Lincoln Memorial, by way of the Washington Monument, to the U. S. Capitol Building, a distance of just about two (2 miles; that is a good hike for even most out-of-shape American fast-food eaters). But the beautiful capital of our country has urbanature aplenty, from DuPont Circle to the Anacostia River, from the Masonic Memorial in Alexandria to Rock Creek Park of he city’s west side. Our Mall includes the Smithsonian’s Castle and its Air & Space Museum, as well as the Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of Art, the Hirschorn Museum and its Sculpture Garden and the Museum of African Art, the new Museum of African-American History and Art, the American History Museum, and the Museum of the American Indian, the Freer Gallery, the Sackler Gallery, the Arts and Industries Building, and finally the Smithsonian International Gallery. Is that enough for your museum sightseeing? Make sure and extend your stay for an day or two longer than you had planned at first. America’s attic–as the Smithsonian is sometimes called thanks to Spencer Fullerton Baird (a professor at my own Dickinson College) who took its collections from to a few thousand objects to many millions of objects–houses as many separate items as any museum collection in the world. The Baird years were when the Smithsonian became America’s greatest museum collection; in fact, the museum still refers to Baird as America’s Sublime Pack-Rat.

Richmond

Chimborazo Park:

Chimborazo Park is on the hillside site of a huge hospital that once cared for over 75,000 wounded Confederate soldiers (see contemporary Library of Congress photo below). As one of the largest military hospitals ever built, during the three years that it operated (1862-1865), the mortality rate of the Chimborazo Hospital was slightly under 10%; this means that somewhere approximately 7,500 of these injured did not survive their stay in the on this scenic hill above the James River. The park is named for the highest mountain in Ecuador, a dormant volcano that is also the highest peak near the world’s equator.

This miniature statue of liberty replica (left), was a gift from the Boy Scouts of America. Its plaque reads: “With the faith and courage of their forefathers who made possible the freedom of these United States the Boy Scouts of America dedicated this copy of the statue of Liberty as a pledge of everlasting fidelity and loyalty 40th Anniversary Crusade to strengthen the arm of liberty, 1950.”

Hollywood Cemetery:

Graveyards exist as particularly interesting examples of urbanature; in many cities they form some of the largest sections of relatively untouched flora and fauna in otherwise urban surroundings. Indeed, cemetery grounds often provide not only resting places for the dead, but also important historical sites, tourist attractions, and gardening areas. While not among the largest cemeteries in America–its 130 acres overlooking the James River near the city-center is a long way from Long Island’s Calverton cemetery (at 1,045 acres)–here, in Richmond (as might be expected), are final resting places of more Confederate Civil War generals than in any other cemetery in the country.Among the 18,000 Southern soldiers who were interred here, approximately 7,000 were bodies that were moved from their original burial sites on the Gettysburg Battlefield. As the website describes part of Hollywood’s distinction: “Among the important people interred there are two American presidents, John [sic James] Monroe, the fifth president and John Tyler, the tenth. Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States, is also buried here as are his son and daughter.” A total of 25 confederate generals are buried on the grounds. Along with these rebel commanders, the 18,000 enlisted confederates are commemorated with a 90-foot tall granite pyramid completed in 1869.

Cemeteries and Urbanature

Cemeteries are somewhat odd as urbanatural site, perhaps, and yet they preserve as much urban open space as any other form of city land use. This has, in fact, become a controversial topic in recent years, as Alexandra Harker notes in her essay “Landscapes of the Dead: An Argument for Conservation Burial”: “The American funeral industry has long influenced how and where we bury the dead. Current industry-standard burial practices harm the environment through the use of embalming and hardwood caskets. [There is] a different model for burials, one which will preserve open space, incorporate cultural landscapes into cities and regions, and increase the ecological sensitivity of burial practices and social acceptance of death as a natural process. Conservation burials support ecological restoration and can help finance public open space and preserve ecological lands. City planners are in a unique position to promote this new model of burial practice by framing cemeteries as green infrastructure.” In these “conservation burials,” bodies are buried without embalming (which is in fact currently not a law in any state in the U. S.) and without caskets; instead; they are simply wrapped in a cotton sheet and placed in the grounds. Cremation, of course, also provides an alternative to traditional burial techniques and today can be used to “turn” the loved on into a tree (see “Bios Urn” or “Eternitrees) or a diamond (see ). And see, also, “Ten Crazy Things to Do When You’re Dead”: the ten include becoming a vinyl record, the structural basis for a coral reef, or simply have your body left on top of a mountain, as the Tibetans do, “for the critters to have at it.”

Atlanta

*Home Page *** Urban Urbanatural Roosting *** Natural Urbanatural Roosting *** Bibliography*