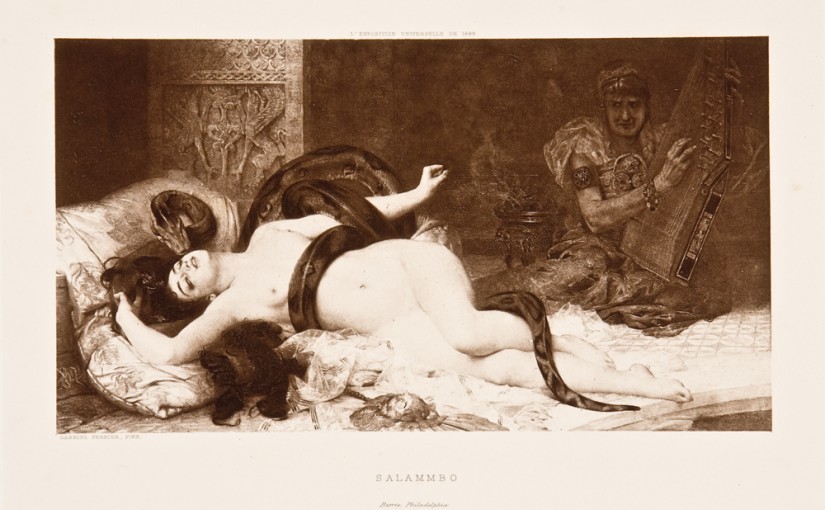

I was particularly drawn to the overtly sexual Salammbo image in the Trout Gallery and how it actually seemed very similar to the cover photo on Christina Rossetti’s children’s poem Goblin Market. Salammbo shows a luminous, white woman, naked except for a snake draped and intertwined around her body. The snake seems locked around her torso, ultimately in control, yet the woman has a look of pleasure on her face. A man looks on from a shaded corner, playing an instrument that may tame the snake and the woman. Similar to this, the cover for Goblin Market depicts a young, pale woman, being crowded by grimy goblins. She wears a white dress that blends in with her skin and serves to accentuate her figure. The goblins play the same role as the snake in the Salammbo engraving as they hold the woman in place and drape themselves over her body. The woman, though in a seemingly compromising position, does not appear upset, and instead looks longingly into the distance.

When reading The Goblin Market it became most interesting to me that forces of nature control these two women in the images. In Rossetti’s poem, Laura, one of the sisters in the story, is drawn to these goblin men selling luscious fruits and is described as having “stretched her gleaming neck” towards them and their fruits (Rossetti 3). Once she gives a locket of her golden hair to them (literally giving a piece of her body over to them) she devourers the fruit and “sucked and sucked and sucked the more / Fruits which that unknown orchard bore” (Rossetti 4). She enjoys the fruit and giving in to her desire, even though she knows it is wrong. Similarly, the woman in Salammbo looks to be in bliss despite the snake and on-looking man. In both cases, natural elements, whether it be fruit or animals, overtake the women as men (male goblins counted) watch on. Goblin Market is meant to be a warning against engaging with forbidden temptations, yet the text shows a woman receiving some amount of ecstasy from it. The Salammbo image also serves to warn the viewer of the exotic snake and creepy man, yet lures the viewer in to the women with the look of pleasure on her face. In this way, it seems like both instances are overtly showing exoticism as dangerous and seductive, yet also proving the pleasure that can be taken from engaging with these exotic experiences. If these exotic experiences can be replaced with sexuality, a type of danger and otherness to those who want to keep up certain appearances in the Victorian era, the two sources might show a hidden look into the joys of engaging with forbidden sexual acts or sexuality.

Joseph Marie Augustin Ferrier, Gabrial. Salammbo. 1889. Trout Gallery, Carlisle. Web. 3 Nov. 2016.

Rossetti, Christina. Goblin Market and Other Poems.New York: Dover Publications, 1994. Print.

What I find exceedingly interested in regard to the points you’ve made in this post is that both temptations are completely natural. By that I mean one is an animal (albeit exotic) found in nature and the other temptation is fruit, grown and coming from nature. Going off of this however is that although both of these are natural, I think the reason they prove to be effective temptations has to do with the role of the “other” (Orientalism, maybe even occultism) implemented by the tempters. For example, the snake is manipulated potentially by the individual in the background, perhaps a “snake charmer” with the lyre. The fruit is manipulated by the goblins in that they grow the fruit themselves with their own special means. I think this is a crucial comparison because it depicts that scary tempters (whether they be from another race, socioeconomic status, or other from the tempted) are effective because of their manipulation of natural, somewhat ordinary things, not because of extremely supernatural agents.