Victorian ideas of a society being “redeemed by art” as described by Richard Altick rest on the function of looking. Culture, to some Victorians, was “a function, in the first instance, of the eyes”—the quality of the “inner life” was determined by what someone was surrounded with, ideally beautiful things (281). This is quite similar to medieval English ideas of sight, with the differences being physical. To the Victorians, beauty improved your inner self, including your morality and happiness, hence helping society. To English folks in the Middle Ages, looking upon beauty not only improved your morality and happiness, but also your physical health and appearance. In fact, it was a common romantic trope (as in medieval romances as a genre) that physical beauty was equated with inner beauty as well as wealth. Though a fictional trope does not translate directly into the real world, its existence does still reflect a cultural trend. It is one similar to the Victorian equation of beauty in your surroundings with morality as well as wealth.

But to an extent, the medieval equation of physical beauty in the person with all these things is actually shockingly similar to the Victorians. While I have no evidence of any Victorian writer arguing that in the real world, beautiful and healthy people are always surrounded by beauty and wealth and have perfect souls, Victorian prints—works of fiction, much like medieval romances—strongly suggest the idealistic notion.

I’ve had the recent privilege of looking at a collection of prints that were distributed in Victorian England, particularly ones produced by the Illman Brothers that feature women as the main subjects. Because I am focusing on images with women, I will not be considering if the equation of beauty with morality with health with money with art also applies to men. I will, though, be focusing on how it might apply to women, and the significance of that gendered analysis.

“Expectation” is a standout example of one of these art women being surrounded by beautiful objects. She is the beauty standard—a soft face, accessorized hair, and an expensive, modest dress. The luxury of her clothing, as well, suggests equating wealth with beauty. Furthermore, she is framed by angels, flowers, swirls, and fruits. Angels suggest both purity and innocence, a subtle comment on the woman’s morality as represented by the objects or art that surrounds her. Whether it reflects her morality, or causes her normative morality, is unclear. Flowers adorn lots of art—stereotypically beautiful objects that bring joy and life, also perhaps suggesting the youth and femininity of the woman here. Decorative lines, as well, are shown. Interestingly, there is also fruit hanging from the frame. This ripe fruit might imply fertility and health for the woman shown. Through her appearance and these surrounding objects, then, not only the morality, but the external beauty and physical health of the woman is emphasized.

“Health and Beauty”’s title already carries a suggestion that the central woman is both physically fit and gorgeous. She stands tall and proper, an image of extravagance on top of those two previously mentioned features. Not only does her clothing display extra fabric, intricately patterned, but her environment is one that is grand and expensive. A large classically-styled pillar can be seen in the background, along with a decorated railing adorning the steps she descends. The woman’s health and beauty, then, is native to her wealthy and art-filled environment.

“Fannie’s Pets” is an interesting image for multiple reasons. First of all, it features two figures, a woman and a man, as opposed to the previous images only featuring one central character. Second of all, it includes animals as central elements. The woman, presumably Fannie, is assumed to own every shown bird and mammal in the image; their shapes and appearances suggest both elegance (such as the birds) and sweetness (such as the rabbits). Her ownership over them implies that she is wealthy, one of the features in the equivalent list. Because they demonstrate a bond with her, flocking to her side, she is also implied to be moral. The way the animals surround her and gaze up at her evokes a motherly image of Fannie, as well as indicates that she is a trustworthy individual. Finally, a man exists in he image to one side, also gazing in awe at the scene unfolding before him. His awestruck expression may also speak to Fannie’s kind and motherly qualities, as well as perhaps her physical beauty that attracts the man’s gaze. To conclude, these three above images are only some of the most prominent examples of Illman Brother’s prints that suggest fictionalized women must check off a list of desirable qualities, and that having one of the qualities inherently leads to the others. This draws a tentative connection between medieval romance genre ideas of moral character, class, and physicality, and Victorian attitudes towards art.

Works Cited:

Altick, Richard. “Art and its Place in Society.” Victorian People and Ideas, Norton: New York, 1973.

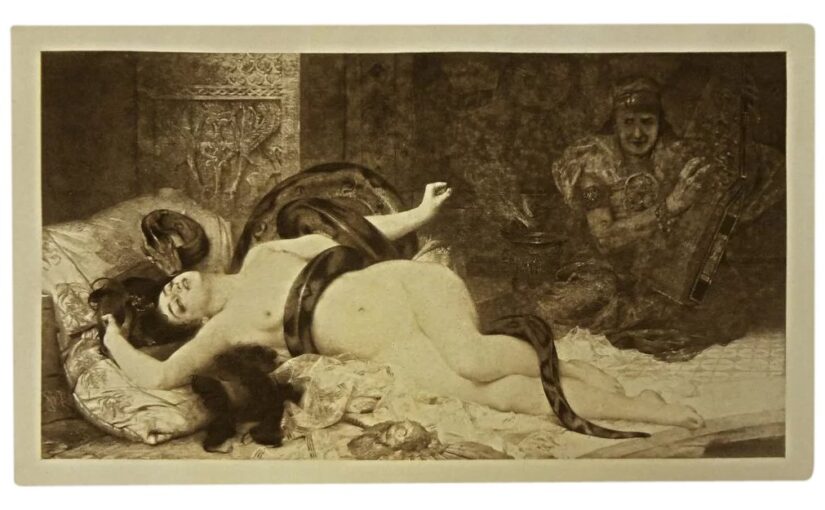

When I encountered this image during our class’s trout gallery visit, it quite literally stopped me in my tracks.

When I encountered this image during our class’s trout gallery visit, it quite literally stopped me in my tracks.

Image credit: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ebay.com%2Fitm%2F205082576172&psig=AOvVaw2PII8eU6S7qjGt45W5nJ7w&ust=1744202402683000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBQQjRxqFwoTCPDkk7m6yIwDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAJ

Image credit: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ebay.com%2Fitm%2F205082576172&psig=AOvVaw2PII8eU6S7qjGt45W5nJ7w&ust=1744202402683000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBQQjRxqFwoTCPDkk7m6yIwDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAJ