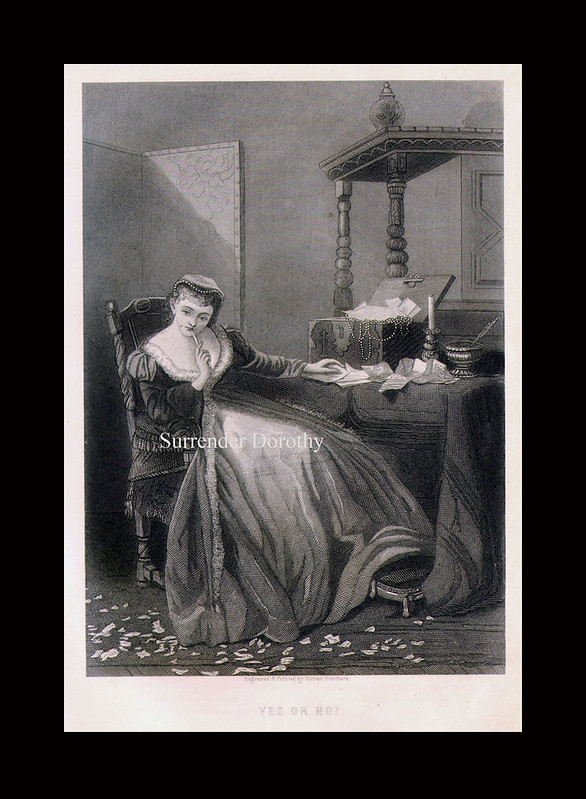

The engraving “Yes or No?” depicts a woman deeply contemplating a decision (presumably a marriage proposal) and writing and rewriting the letter with her response. Her desk is in disarray and there are torn up pieces of paper around her on the floor as she sits at the desk looking troubled. She also has several pages of letters on her desk, messily strewn around. When I first saw this image, I was curious as to what this etching said about a woman’s agency in the Victorian Era. In one sense, she (presumably) has a decision to make whether she wants to marry him or not. However, at the same time, the fact that she is clearly unable to make the decision strips her of that same agency because she can’t make up her mind.

This image reminds me of when Laura went to Sir Percival to tell him that she loved someone else because these depictions of agency in women are different.. While Laura ultimately lacks agency, she tries to give Sir Percival an option in order to control her own destiny. Laura did not have much, if any choice in whether or not she was to marry Sir Percival even though she tried because she was in love with Walter. In the image, the woman does have the power to say yes or no but can’t make up her mind.

Both Laura and the woman in the etching lack agency but for different reasons. Laura doesn’t have power over her own fate but this woman does. However, this woman’s inability to make up her mind strips her of that agency and depicts her as if someone has to make the decision for her (presumably a male). If a woman needs to rely on some one else to make her decisions, she doesn’t have very much agency at all. So, while these two different characters or images of women are slightly different in their agency, they both ultimately lack control over their own lives.