The 19th century witnessed a dramatic expansion of the British Empire, bringing with it not just military and economic power, but also a fascination with the cultures of the conquered territories often referred to as the “East”. This fascination found substantial space in the arts, where Orientalist painting emerged as both a reflection of imperial ambition and an imaginative reworking of exotic “otherness.” One powerful example of this is Fête of the Prophet at Quad-el-Kebir by Fredrick Arthur Bridgeman, a richly detailed work that encapsulates the Orientalist gaze.

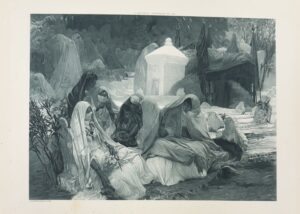

Orientalism, as defined by Edward Said, refers to the depiction of Eastern societies as exotic, mysterious, and often inferior to the West. In this painting, Bridgman portrays a religious festival emphasizing the exotic nature of the scene. The composition, featuring richly adorned figures and elaborate architecture, caters to Western fantasies of the East as a land of mysticism, particularly as it pertains to women in their cultural clothing.

Relating this idea to the artist, Bridgeman, an American, travels to North Africa in 1872 and marks a pivotal moment in his career. He journeyed through Algeria and Egypt, producing approximately 300 sketches that would serve as the foundation for many of his subsequent paintings. These works, characterized by their depictions of Eastern life, earned him recognition in both Europe and America.

While based on a real event, the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday, Bridgeman amplifies its suspense to create a visual experience steeped in drama. The viewer is invited not to understand the meaning of the ritual but to consume it as exotic entertainment. This is further supported with the women in the background of the painting, fading into one another, lacking individual identity. Bridgman’s depiction of these figures supports the Orientalist narrative of Eastern society as a faceless, homogenous mass, especially in regard to gender roles. In this context, Muslim women are not portrayed as active participants in their own cultures, but rather as passive, decorative elements in a scene interrupted by the Western gaze. This marginalization reflects a broader Western tendency to view Muslim women as silent, oppressed, and mysterious

Here, Bridgeman projects Victorian fantasies onto the Islamic world. In the painting, there are no hints of colonial interference, creating a fixed world, stuck in the past, thus needing Western guidance. Additionally, there is little theological focus in the figures, showing that religion in the East is portrayed not as a moral system but rather as ecstatic, tribal, and emotionally charged. Ultimately, beauty, strangeness, and emotional intensity are prioritized over cultural understanding making it an example of the Victorian orientalist imagination.

Reading between the lines and walking across intersections,

JAY WALKER