While the term psychopath was not used to describe the charismatic, non-empathetic monsters we know today (ie- Bundy, Manson) at the time Woman in White was written, when reading the character of Count Fosco from the present, there is no doubt he meets several if not most characteristics of how one would define a psychopath today. The OED describes a psychopath as “a mentally ill person who is highly irresponsible and antisocial and also violent or aggressive”. This more modern meaning of the word was first used in 1885. Using the revised Hare Psychopathy Checklist, I will now provide traits of a psychopath backed by textual evidence to show how Fosco meets a myriad of them.

- Glib and superficial charm- This trait can also be described as charisma. Marian admits “I am almost afraid to confess it, even to these secret pages. The man has interested me, has attracted me, has forced me to like him…and how he has worked the miracle, is more than I can tell” (217). Marian realizes something is off about him but cannot help her attraction to him.

- Criminal Versatility- This includes taking great pride in getting away with crimes. This is evident when the Count and Glyde are discussing wise and foolish criminals. “There are foolish criminals who are discovered, and wise criminals who escape…A trial of skill between the police on one side, and the individual on the other…But I don’t see why Count Fosco should celebrate the victory of the criminal over society with so much exultation” (233).

- Promiscuous Sexual Behavior- I see Fosco as being very much like Christian Grey in his mannerisms of control. He is described as resembling “Henry the Eighth himself” (218) which hints that he is marred by infidelity. Fosco is also said to control the Countess with “rod of iron with which he rules her never appears in company- it is a private rod, and is always kept up-stairs” (222) which seems indicative of bondage and/or sexual abuse. He is also known to have a taste for sweets “‘A taste for sweets’ he said in his softest tones…’is the innocent taste of women and children. I love to share it with them'” (289). This description seems to hold undertones of cannibalism as well as pedophilia.

- Cunning and Manipulativeness- Fosco even describes himself in this way “I, Fosco, cunning as the devil himself, as you have told me a hundred times” (324). This trait also ties in with the trait of parasitic lifestyle in terms of financial exploitation. Glyde realizes this in Fosco when he states “Some of the money I want has been borrow for you. And if you come to gain, my wife’s death would be ten thousand pounds in your wife’s pocket” (327). Fosco also uses his wife to carry out his cunning acts, like when the Countess reports that Laura called Fosco a spy, and the Countess drugged Fanny and replaced the letters Marian had written.

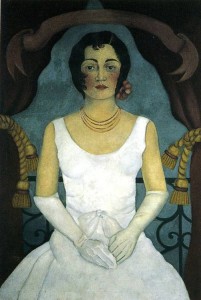

Reading Fosco as a psychopath from the modern definition is enlightening in understanding the text as a whole because we can recognize this period as being one rich in the study of psychological disorders, their definitions, and treatments. It is evident that people exhibiting modernly defined psychopathic traits did exist although the term for them had not been coined. The earliest definition of psychopath comes from 1864, 4 years after WIW is published. This definition is probably even more interesting when studying WIW because up until 1885, psychopath was actually used to describe “a doctor or other practitioner specializing in the treatment (or claiming to treat) disorders of the mind”. In this way Fosco meets the definition of a psychopath on a dual level as Mr. Dawson claims Fosco is a “Quack…dying to try his quack remedies” (364-365) when Marian is in poor health. Fosco claims to be a man with medical talent and the image of him at Blackwater with Marian, Laura, and his wife, takes on the dynamic of Fosco as the psychopath or asylum leader, with the women as his patients forced to conform to his will. The Countess provides proof of his “success” at healing feminine mental malady, as the once self-proclaimed feminist is now his loyal servant. In his role as psychopath-doctor he still maintains a trait of psychopath-modern: endless obsession with control- as if the women were his pure, white mice.