Laura is a 1944 film noir directed by Otto Preminger and based the 1941 novel Ring Twice for Laura by Vera Caspary (IMDb). There are several eerie coincidences between this text and The Woman in White. (As it turns out, a number of online sources suggest that Caspary was inspired by Wilkie Collins’s 1868 Moonstone—though none of my sources cites a primary source for this information). In terms of characterization, a wealthy young woman named “Laura” Hunt is courted by multiple men—one named “Waldo,” who is a combination of Walter’s possessive condescension; Count Fosco’s aged, effeminate, well-dressed, world-wise manipulation; and Sir Percival’s constant concern with appearances. Plot-wise, Laura is known to be murdered before the film begins, and Detective Mark McPherson spends much of the film trying to pin down the details of her murder—at which point he discovers that Laura is alive, and spends much of his time trying to find evidence of what really happened. Narratologically, the story is established through first-person narratives by multiple characters—though unlike Laura Fairlie/Glyde/Hartright, Laura Hunt does tell a portion of her own narrative. One of the most interesting parallels between the texts occurs when Detective McPherson falls in love with Laura’s portrait, before he has met her and while he still thinks she is dead:

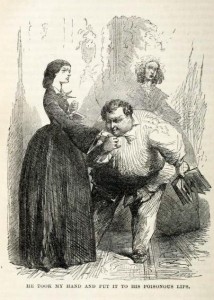

Though the portrait is not McPherson’s own handiwork, this scene is parallel to Walter’s enamourment with his own watercolour portrait of Laura, almost in substitute of Laura herself: “A fair, delicate girl in a pretty white dress, trifling with the leaves of a sketch-book, while she looks up from it with truthful, innocent blue eyes… Think of her as you thought of the first woman who quickened the pulses within you that the rest of her sex had no art to stir” (Collins 52). In both situations, a woman is defined by her physical features through a work of art that she herself did not create, and her worth is determined by the interest she can arouse in a man—in the effect the gendered “art” of her appearance has on his “pulse,” his body. Though both McPherson and Hartright claim to love their “Lauras” in the end, there is something discomfiting about the way they reflect on the beginnings of their love by referring back to their attraction to a portrait, rather than to the woman who inspired it—their male gaze is directed at a female art object, and their male hearts have undisclosed motives. The eerie discomfort created when McPherson falls in love with (the theoretically dead) Laura’s image exemplifies the creepiness of Walter’s consistent memory of his watercolour portrait of Laura, even after the woman he fell in love with is lost to child-like behaviors resulting from trauma. An attentive reader must question the validity of a “love” that roots itself first and foremost in a stylized image.