In Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, critic Rosemary Jackson offers a generic analysis to help better understand fantasy. To Jackson, “[t]he fantastic exists in the hinterland between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary,’ shifting the relations between them through its indeterminacy” (35). As a genre of subversion, fantasy tests the bounds of reality. By “[p]resenting that which cannot be, but is, fantasy exposes a culture’s definitions of that which can be” (23). Fantasy primarily accomplishes its subversive goals by using motifs of invisibility, transformation, and, notably, non-signification. Frequently, fantasy foregrounds “the impossibility of naming [an] unnameable presence, [a] ‘thing’ which can be registered in the text only as absence and shadow” (39). This emphasis on non-signification easily applies to Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1871). According to Jackson, “Carroll’s Alice books…reveal his reliance upon portmanteau words and nonsense utterances as a shift towards language as signifying nothing, and the fantastic itself as such a language” (Jackson 40). Alice enters a world of “semiotic chaos, and her acquired language systems cease to be of any help” (141). In Wonderland and the Looking-Glass, “[t]he signifier is not secured by the weight of the signified: it begins to float free” (40). Though Jackson provides a thoughtful and thorough analysis of the novels, I would argue that she fails to account for a fundamental aspect of Carroll’s texts: John Tenniel’s illustrations.

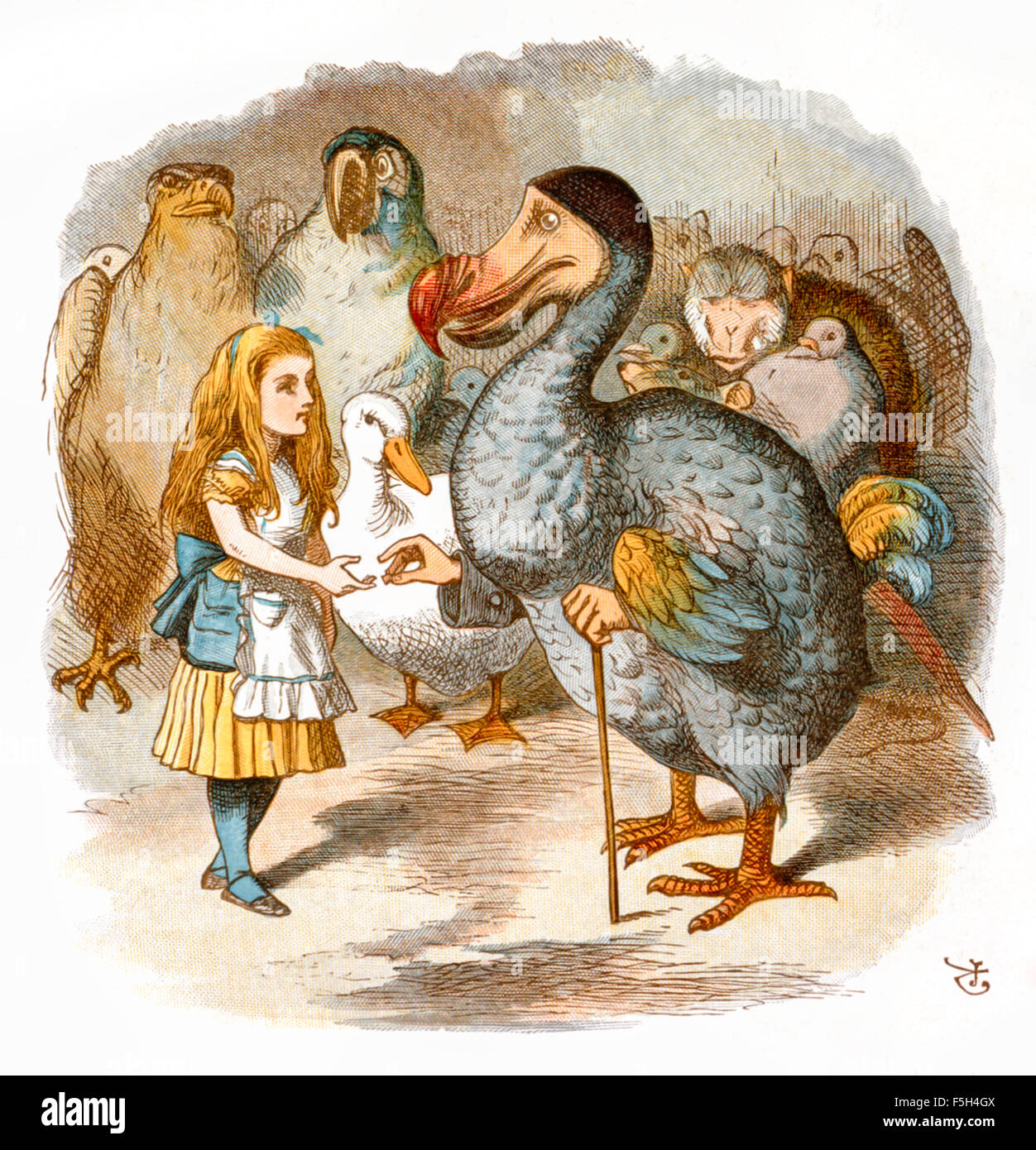

As Jackson points out, fantasy highlights “problems of vision” (45). “In a culture which equates the ‘real’ with the ‘visible’ and gives the eye dominance over other sense organs,” she writes, “the un-real is that which is in-visible” (45). Yet in the Alice books, Carroll makes the unreal visible and the unspeakable seeable through John Tenniel’s illustrations. Carroll and Tenniel worked in close collaboration when designing the Alice illustrations. In fact, Tenniel might have even based his drawings on original sketches created by Carroll himself (Hancher 39). Historian Michael Hancher rightly argues that Tenniel’s illustrations “make up the other half of the text, and readers are wise to accept no substitutes” (5). Without both halves, the Alice books do not work. The illustrations do not serve as mere adornments to the plot; they actively contextualize and shape it.

At multiple points in the text, Carroll does not even attempt to describe the fantastical creatures he creates. Instead, he defers to Tenniel’s illustrations. When Alice encounters “a Gryphon lying fast asleep in the sun,” the narrator directly addresses the reader in a parenthetical aside: “If you don’t know what a Gryphon is, look at the picture” (80). Similarly, when Alice encounters the King of Hearts at a trial, she notices he wears “his crown over [his] wig” (94). Again, instead of describing this unusual attire, the narrator instructs the reader to “look at the frontispiece if you want to see how he did it” (94). The unspeakable—or at least the hard to explain—is made knowable through illustrations.

At other points in the text, Tenniel’s illustrations ground Carroll’s nonsense words by attaching them to concrete, visible objects. When Alice reads “Jabberwocky,” for instance, she remarks that the poem is “rather hard to understand” (132). As readers, we know that this is because the poem is nothing but nonsense; Carroll explicitly tells the reader in the preface that the terms in “Jabberwocky” are “new words” of his invention (115). Still, Tenniel provides the nonsensical word “Jabberwocky” a signified object to cling to. Before looking at Tenniel’s illustration, the reader only knows that the evil Jabberwocky has “jaws that bite,” “claws that catch,” “eyes of flame,” and some sort of “head” (130). After looking at Tenniel’s illustration, though, they can completely fill in the blanks left by Carroll’s sparse description. Tenniel takes significant artistic liberties, creating a monstrous creature with wings, antennae, whiskers, scales, and a long, twisting tail (131). The miniature warrior at the creature’s feet is undoubtedly the “beamish boy” of the poem, poised to strike the creature’s head off with his “vorpal sword” (130). Since the sword of Tenniel’s illustration looks like a typical knight’s weapon, the reader can assume that the nonsensical adjective “vorpal” means something along the lines of “sharp” or “dangerous” rather than “curved” or “tiny” (131). Similarly, the average trees in the background of the illustration indicate that a “Tumtum tree” is not a particularly remarkable plant (130). As far as the viewer can see, the Tumtum trees in the forest do not grow candy or sprout upside-down. According to Tenniel’s illustration, a Tumtum forest looks just like any other. Jackson argues that Carroll’s nonsense words “float free” without signified objects (40). However, she fails to recognize that Tenniel’s illustrations pull them back to the ground, limiting their potential meanings.

Tenniel’s illustrations also modify Carroll’s overall plot. When Alice meets the White King in Through the Looking-Glass, she encounters his two messengers, Haigha and Hatta. Nothing in the text indicates that either of these characters is familiar to Alice; she speaks to both of them as if she has never met them before. Tenniel’s illustrations might raise some alarms, however. Haigha is depicted as a rabbit, though nowhere in the text is he described as having any leporine features (196). Meanwhile, Hatta is depicted wearing an oversized hat with a price tag fastened to the side (198). For readers of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the illustrations would be immediately recognizable as the Hatter and the March Hare. Hatta looks identical to the Hatter, while Haigha shares obvious physical similarities to the March Hare—namely two large ears. There are some slight differences between Haigha and the March Hare. In the first novel, the March Hare seems to have a darker fur color and darker eyes than Haigha (59). Still, a rabbit near the Hatter unmistakably calls to mind the March Hare. Without Tenniel’s illustrations, it would never be clear that residents of Wonderland can pass into the Looking-Glass alongside Alice. Of course, Carroll’s text implies this crossover. The name “Hatta” clearly echoes the name “Hatter,” while the name “Haigha,” according to the White King, is meant to rhyme with “mayor,” meaning it would be pronounced “hare” (195). Still, Carroll never draws any connections explicitly. Tenniel’s illustrations, on the other hand, leave little room for doubt: the Hatter is certainly one of the White King’s messengers, while the March Hare is likely his other. Once again, Tenniel reduces the ambiguity of Carroll’s text with visual cues for the reader.

At the beginning of the first novel, Alice asks herself a salient question: “[W]hat is the use of a book…without pictures or conversations?” (7) Carroll’s fanciful tales and Tenniel’s beautiful illustrations seem to answer Alice directly, asserting that a book is nothing without its pictures. The marriage between Carroll’s words and Tenniel’s drawings simultaneously complements and complicates Jackson’s definition of fantasy. On the one hand, their partnership emphasizes “that which cannot be said, that which evades articulation [and] that which is represented as ‘untrue’ and ‘unreal’” (Jackson 40). When words fail, Carroll is forced to defer to Tenniel to fill in the blanks with images. As in Lovecraftian horror, some creatures and settings simply defy language. On the other hand, Carroll and Tenniel’s collaboration challenges the notion that fantasy must create a complete “disjunction between word and object” (38). Tenniel provides the reader some ground to stand on, even as it shifts and shakes beneath their feet. New words and new creatures are given life through seeing them. Tenniel clarifies that smoking caterpillars have hands (38), Mock Turtles have bovine heads (83), and talking flowers have tiny faces (134). Carroll’s nonsense is made less nonsensical through Tenniel’s refashioning of his text.

One could hypothetically read the Alice books without Tenniel’s illustrations, but they would miss a fundamental aspect of the text: vision. Throughout her journeys, “Alice learns by looking, as does the reader, the other eye-witness of both her books” (Hancher 246). Carroll’s text suggests that a mere gaze can refigure, refine, and redefine language as we know it. To put it more plainly, to see is to mean, and to mean is to see.

Works Cited

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Penguin Classics, 2015.

Hancher, Michael. The Tenniel Illustrations to the “Alice” Books, 2nd Edition. Ohio State University Press, 2019. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv30m1f0f. Accessed 7 Apr. 2025.

Jackson, Rosemary. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. Routledge, 2003. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=3d1a59e5-395f-3130-b732-52a5d20930b1. Accessed 3 Apr. 2025.