By Ryan Schutte

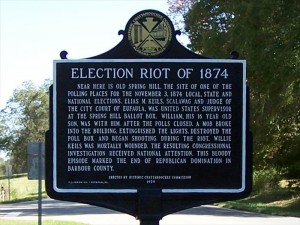

On November 3, 1874, Captain A.S. Daggett of the 2nd U.S. infantry sat at his hotel window and watched horrified as bloodshed ensued outside the polls on the main street of Eufaula, Alabama on election day. An altercation outside a polling station between a black Republican, Milas Lawrence, and white Democrat, Charles E. Goodwin, quickly turned into a massacre after Lawrence was stabbed in the shoulder by Goodwin’s companion, William Dowdy. Prepared for conflict, unofficial white militia men shouted, “Fall in Company A; Fall in Company B,” and began firing an estimated 500 shots into the mass of unarmed black men on the street. When the dust had settled, seventy-five men were found wounded and seven dead. More life was lost later that night in the neighboring town of Spring Hills, when Democrat intruders broke into the house of the Republican city court judge Elias Hills and opened fire, killing his 16-year-old son, Willie. Overshadowed by the carnage of that day was the large-scale destruction of ballot boxes, the theft and burning of hundreds of casted ballots, as well as the denial of thousands of black men from the polls. Democrats swept the county elections, and symbolic of the rest of the nation, had a new party representing their district in the House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War. The events of Eufaula in 1874 exemplify the militaristic arm of the Democratic Party that was taking hold in southern politics, and paired with inadequate federal response, effectively eliminated blacks’ newfound rights granted by the 14th and 15th amendments [1].

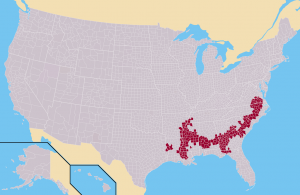

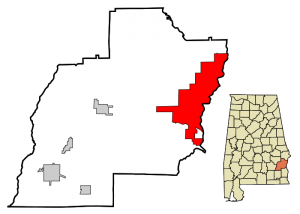

Sitting just below America’s Black Belt along the Chattahoochee River, Eufaula, like the rest of the nation experienced a period of expansion in the right to vote with the Civil War’s end [2]. Despite opposition from Southern states and President Andrew Johnson, the majority Republican Congress passed the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing newly freed blacks citizenship, due process, equal protection under the law, and, most importantly, the right to vote [3]. The democratization of the right to vote was, by no means, accepted without resistance and in a petition sent to Congress, Alabama conservatives referred to the newly enfranchised blacks as, “…ignorant generally, wholly unacquainted with the principles of free Governments, improvident, disinclined to work…dishonest, untruthful, incapable of self-restraint, and easily impelled…into folly and crime…” [4]. By 1874, “White Northern disillusionment with Reconstruction” had set in, and the nation was in the midst of an economic downturn like never before. As a result, black civil rights expansion became increasingly unpopular, and southern blacks were left alone in the fight to protect their newfound voting rights [5].

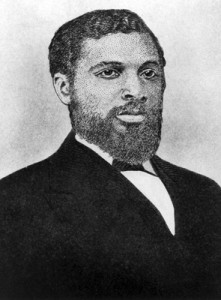

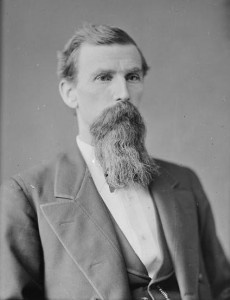

Throughout the summer of 1874, racial and political tensions in Eufaula had reached its climax as white conservatives hoped desperately to redeem political control from the Republican coalition of carpetbaggers, scalawags, and enfranchised blacks. To Barbour County Democrats’ dismay, influence from the opposition political alliance often resulted in the election of Republican candidates in local elections– their current representative in Congress a leading black politician, James Rapier [6]. Rapier, born free in the slaveholding south in 1837, won his seat in December of 1873 and worked hard during his tenure in the defense of black rights. In his first address to Congress, Rapier reaffirmed this stance as he proclaimed, “I cannot willingly accept anything less than my full measure of rights as a man, because I am unwilling to present myself as a candidate for any brand of inferiority.” Consequently, Alabama’s white conservatives were determined to win the November congressional election in order to save the state from “Negro Rule” [7]. In June of 1874 at the state convention, Democrats nominated former Confederate, Jeremiah Williams, for the 2nd Alabama congressional seat and adopted the Pike County Platform [8]. The platform read:

“[Nothing] is left to the white man’s party but social ostracism of all those who act, sympathize or side with the negro party, or who support or advocate the odious, unjust, and unreasonable measure known as the civil rights bill; and that from henceforth we will hold all such persons as enemies of our race, and we will not in the future have intercourse with them in any of the social relations of life [9].”

In essence, the Alabama Democratic platform encouraged the ostracism of white Republicans in hopes that deprivation of a satisfactory social life could change their opponents’ voting behavior or force them to move [10]. Later that Summer, local Democrats took more extreme measures to defeat the Republicans when they formed the “White Man’s Club of Eufaula.” Similar to the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan, members of the organization attempted to force local black voters to pledge loyalty to the Democratic party [11].

On top of the pressures provided by the Democrats, a faction within the local Republican Party had materialized over the pending impeachment of Judge Richard Busteed. Despite his determination to stay out of the conflict, Rapier was forced to give in when armed protestors showed up at the Republican nominating convention in August, threatening violence unless their demands were met. To many voters, Rapier’s surrender to the violent faction of Republicans reeked of corruption, and following the event one southern newspaper noted the Democrats disapproval of the “bargain” [12] . In a political misstep, Rapier went back on his pledge a few days later, and leading up to the election, his chances of earning a second term were in question [13].

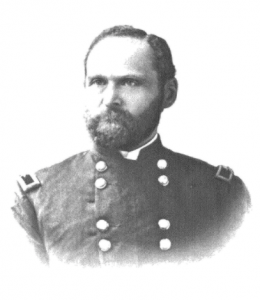

Nothing clouded the political landscape more than the growing “atmosphere of violence” as election day neared, and according to historian, Melinda M. Hennessey, city court judge, Elias Keils “personified” the political struggle in Eufaula. Keils, a former secessionist, but now a middle-aged Republican leader in Eufaula, had been elected to the city court in 1870. In his four years as city court judge, Keils faced significant political opposition from the Democratic party and was accused of protecting guilty blacks in the county. As the midterm election of 1874 neared, Keils recognized the growing political and racial tensions throughout Bourbon County; and, seeking support and protection, wrote to Alabama attorney general, Benjamin Gardner, as well as U.S. Marshall, Robert W. Healy, on several occasions. Finally, less than two weeks before the election, the marshall answered his pleas, and a company of soldiers led by Captain A.S. Daggett was sent to oversee the elections. However, just as the soldiers from the U.S. 2nd infantry arrived in Barbour County, their ability to aid the election was severely restricted by General Order No. 75. General Irwin McDowell, Commander of the Department of the South and Captain Daggett’s superior, gave the order, limiting uses for Army troops to enforce writs of U.S. courts and protect Internal Revenue Department agents. Despite Captain Daggett’s protests, he and his troops were essentially powerless, and Keils and the Republican party were forced to proceed with the election unprotected [14].

Despite the lack of protection, black voters were prepared to use strength in numbers, and the night before the election hundreds gathered on the outskirts of Eufaula to prepare for election day. Republican leaders, George H. Williams, Henry Frazer, and Edward Odom organized voters, handed out Republican ballots, and gave orders to travel unarmed on their march to the polls, to “avoid the slightest excuse for white violence…” [15]. On the morning of November 3rd, an estimated 1,500 men marched into the town ready to cast their votes at the town’s polling place. Throughout the morning, blacks and whites, Republicans and Democrats, cast their votes peacefully. However, at 1 o’clock, Milas Lawrence’s and Charles Goodwin’s paths crossed as Goodwin and his fellow Democrats attempted to force an underaged black boy to vote the Democratic ticket. Once the first gunshot sounded, white men ran to their predetermined stations on either side of the street and to second-floor shops above. After about one minute and an estimated 500 gunshots, with the attacked laying in the street, former Confederate brigadier general, Alpheus Baker, yelled with the rest of the men, “Let the Yankees come. We are ready for them” [16]. The violence and destruction in Eufuala on November 3rd kept many blacks and Republicans from the polls and hundreds of casted ballots for the Republican ticket were destroyed. In the end, the Alabama 2nd congressional district went to the Democrats as Jeremiah Williams won the election by 1,056 votes and took his seat at the House of Representatives. After an unsuccessful appeal over the validity of the election, James Rapier was forced to forfeit his position and the election of Williams was confirmed [17].

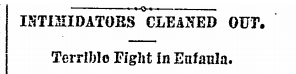

Headline in Georgia Weekly Telegraph a week after Eufaula Election Riot. Courtesy of Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers.

In the aftermath of the Eufaula Riot, Congress launched an investigation into the events that transpired on November 3rd. When the evidence had been collected, the majority determined it was a “premeditated affair to intimidate black voters…” [18]. Southern newspapers, however, responded quite differently, and placed blame on the Eufaula’s black population. A November 10th article from the Georgia Weekly Telegraph twisted the story saying, “The difficulty grew out of the abuse of a negro… by several Radical negroes, chief among whom was one very bad negro named Milas…With an oath against the whites, and daring them to come on, he drew out his pistol and fired”[19]. Not only did the source reverse the attackers and the victims, but made sure to refer to the whites responding to the attack as “gentlemen.” Similarly, another account from a Mississippi paper, The Hinds County Gazette, gave whites a heroic and patriarchal role in the riot, where whites saw the assault and “would not allow it to be done” [20]. The inaccuracy and racial bias of these two accounts demonstrate the growing Democratic influence over the once Confederate states in the years following the war. The lack of consequences for the guilty party following the Eufaula Riots and the ability of Democrats to twist the narrative to their own benefit opened the doors for further acts of violence that would eventually eliminate Republican support and the black vote in the South.

Testimony from Captain A.S. Daggett Describing His Orders and the Riot

Although violence like that of Eufaula was not a commonplace in the 1874 election, the electoral outcome held true throughout the nation. Ninety-four Democratic congressional candidates around the country beat out their Republican adversaries in 1874, and took a majority in the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War [21]. The election marked a success for the Democratic party, not only in congressional seats, but in their newfound ability to control the black vote. While Republicans maintained control over the Presidency and the Senate, the midterm election of 1874 made clear that control over the South was slipping. The election signaled that with little to no federal oversight, southern state and local governments had free reign over elections and could implement policies to nullify the designed effects of the 14th and 15th Amendments. 1874 marked the beginning of the end of the black right to vote in the South– a right that would take almost a century to recover.

[1] Hennessey, Melinda M. “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1976): 118-120. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Owens, Harry P. “The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” The Alabama Review 16, no. 3 (1963): 233. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Wilhelm, Blake. “Election Riots of 1874.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. November 6, 2009. Accessed November 1, 2016. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2484.

[2] “Eufaula, Alabama.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Alabama#Geography.

[3] Pinsker, Matthew. “Understanding the ‘Strange Odyssey’ of the Fifteenth Amendment.” September 20, 2016.

[4] Keyssar, Alexander. The right to vote : the contested history of democracy in the United States. n.p.: New York : Basic Books, 2009., 2009. 73-74, 84.

[5] Robertson, Andrew W. “The Continuing Struggle for Full Rights” In Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History, edited by Andrew W. Robertson, 26-27. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010. doi: 10.4135/9781608712380.n239. [Google Scholar]

[6] Wilhelm, 2009.

Hennessey, 113.

[7] Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. 83-84.

Hennessey, 112.

[8] Hennessey, 114.

“Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 4, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

“Williams, Jeremiah Norman, (1829-1915).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Accessed November 6, 2016. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000512.

Rabinowitz, 83-84.

[9] “Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 3, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

[10] Hennessey, 114-115.

[11] Wilhelm, 2009.

[12] “By Telegraph.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger [Macon, Georgia] 15 Sept. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

[13] Rabinowitz, 85-86.

[14] Hennessey, 112.-113, 116, 119-120.

Owens, 231-232, 226.

[15] Hennessey, 116-117.

Owens, 232-233.

[16] Hennessey, 117-119.

Owens, 233-234.

[17] Rabinowitz, 86.

[18] Hennessey, 123.

[19] “Intimidators Cleaned Out.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger (Macon, Georgia), November 10, 1874. Accessed November 3, 2016. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

[20] “The Election Riot at Eufaula, Ala.” Hinds County Gazette [Raymond, Mississippi] 11 Nov. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 3 Nov. 2016.

[21] “United States House of Representatives Elections, 1874.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_House_of_Representatives_elections,_1874.

Bibliography

“By Telegraph.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger [Macon, Georgia] 15 Sept. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

“Democratic Party Platform of Pike County, Alabama (1874).” Facing History and Ourselves. Accessed November 4, 2016. https://www.facinghistory.org/reconstruction-era/democratic-party-platform-pike-county-alabama-1874.

“Eufaula, Alabama.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eufaula,_Alabama#Geography.

Hennessey, Melinda M. “Reconstruction Politics and the Military: The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1976): 112-25. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

“Intimidators Cleaned Out.” Georgia Weekly Telegraph and Georgia Journal & Messenger (Macon, Georgia), November 10, 1874. Accessed November 3, 2016. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers.

Keyssar, Alexander. The right to vote : the contested history of democracy in the United States. n.p.: New York : Basic Books, 2009., 2009. Dickinson College Library Catalog, EBSCOhost (accessed November 3, 2016).

Owens, Harry P. “The Eufaula Riot of 1874.” The Alabama Review 16, no. 3 (1963): 224-38. Accessed November 1, 2016. RapidILL.

Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982. 83-84.

Robertson, Andrew W. “Congress.” In Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History, edited by Andrew W. Robertson, 904-909. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010. doi: 10.4135/9781608712380.n239. [Google Scholar]

“Strategic Politicians and U.S. House Elections, 1874–1914.” The Journal of Politics, 2005., 474, JSTOR Journals, EBSCOhost(accessed November 4, 2016).

“The Election Riot at Eufaula, Ala.” Hinds County Gazette [Raymond, Mississippi] 11 Nov. 1874: n.p. 19th Century U.S. Newspapers. Web. 3 Nov. 2016.

“United States House of Representatives Elections, 1874.” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_House_of_Representatives_elections,_1874.

Wilhelm, Blake. “Election Riots of 1874.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. November 6, 2009. Accessed November 1, 2016. http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-2484.

“Williams, Jeremiah Norman, (1829-1915).” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Accessed November 6, 2016. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=W000512.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.