Dickinson’s first female African-American student Esther Popel Shaw (1896-1958) was a devoted Latin student, and thirty years after graduation she named classicist Mervin G. Filler as a favorite professor. In the spring of 2017 Michelle E. Hoffer (’17) wrote about the academic experiences of Popel Shaw, with a focus on how she would have encountered the Aeneid. This research was carried out in the archives at Dickinson College with assistance from archivist James Gerencser, and the essay was written as part of the Vergil seminar taught by Prof. Francese.

My research focuses on Esther Popel Shaw, the first African American woman to graduate from Dickinson College, and her journey with the Classics, particularly Vergil’s Aeneid. By examining Aeneid commentaries of the time, as well as archived academic documents such as course catalogs and entrance requirements, I will attempt to reconstruct Esther Popel Shaw’s experience with Vergil at the turn of the twentieth century. I will attempt to paint a picture of her journey through the Latin Scientific Curriculum from 1915-1919, specifically insofar as she was taught to read and interpret the Aeneid and other ancient Latin texts. Ultimately, I aim to answer the question,

“Why were people at this time reading the Aeneid?”

Esther Popel Shaw was born in Harrisburg on July 16th, 1896 and was the first African American woman to both enroll in and graduate from Dickinson College. She graduated from Central High School in 1915 and enrolled at Dickinson the following fall.1 Because Dickinson banned African Americans from living on campus at the time, Esther commuted from Harrisburg each day, electing to pursue the Latin Scientific Course (LSC) of study, which was the same as the Classical Course, but instead of taking Ancient Greek, students in the LSC replaced the Greek with additional studies in modern languages and sciences.2

Esther herself chose to study French, German, Latin, and Spanish.3 An incredibly diligent student, Shaw received both the John Patton Memorial Prize, “an academic award granted annually to one student from each class”.4 and, upon her graduation from Dickinson in 1919, was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa, one of America’s most prestigious undergraduate honors societies. While Shaw held a few jobs following graduation, she spent the majority of her career as a teacher in the Washington DC area, where she taught classes ranging from French, Spanish, and English to algebra and penmanship.5 In addition to teaching, Shaw was also a very well-known poet of the Harlem Renaissance, as well as an active community member for both African American and women’s issues.

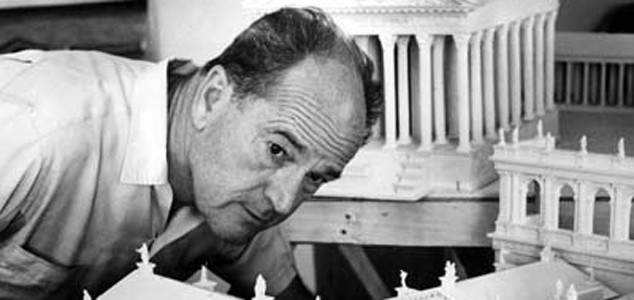

In the fall of 1915, Esther began her journey at Dickinson. And, while she only mentions Latin twice in her diary from her senior year of high school,6 we can surmise from those entries that she had a solid foundation in Latin by the time she enrolled at Dickinson. This foundation may have been a contributing factor in her decision to pursue the Latin Scientific Curriculum, which was taught in large part by Professor Mervin Grant Filler, a man whose reputation still rings through the lobby of the current Classical Studies Department, as it is named in his honor. To say he was a legend both in the Classics and at Dickinson, would be an understatement. Not only was he an brilliant scholar, but was also beloved by his students and his community, as in Shaw’s alumni survey which she completed over 30 years after graduation, she mentions him by name, saying that he gave her both “inspiration and mental stimulation” and considers herself “fortunate” to have been one of his students.7

Grant himself was a true Dickinsonian, as he attended both the Dickinson Preparatory School and then in 1889, enrolled at Dickinson College, graduating both as valedictorian and as a member of Phi Beta Kappa.8 After graduation, he went on to teach Latin and Greek at the Preparatory School and then in 1899 became the professor of Latin at Dickinson College for an impressive 29 years, in which time he was also Dickinson’s 18th president. It was in 1915 that he would have met Shaw, and was very likely the only Latin professor she had in her time at Dickinson. Based on her course of study, records show that Shaw would have taken Vergil her junior year of college with Professor Grant. In his course, Grant stressed Vergil’s “works, life, and literary influence, and readings from the Eclogues and Aeneid VII-XII.”.9 The course was three hours per week for the first half of the year. The second half was devoted to Horace, Satires and Epistles. Through an archived bookstore request from Professor Filler, it is mostly like that in her study of the Aeneid, Shaw would have studied from The Greater Poems of Virgil: Vol. 1, Aeneid I-VI by Greenough and Kittredge, published in 1895.

However, just as today, the Aeneid is open to incredible amounts of interpretation. Thus, in order to reconstruct how Shaw may have been taught to view this great work, it is necessary to examine both the Greenough text, other commentaries of the time, and the competing cultural climates at Dickinson itself. In the early 1900s, Latin was still an entrance requirement for Dickinson, including “six books of the Aeneid” and “reading at sight of easy passages from Caesar, Cicero, and Vergil” for those wanting to pursue either the Classical or Latin Scientific Courses of study. This makes sense then why Professor Filler’s course specifically focuses on books VII-XII, as students were expected to be extremely well versed with the first six upon completing high school. Both of these facts show how valued the Classics still were in academia, both high school and undergraduate. Even in a public high school, students were being drilled and versed in the Latin so that they might be prepared for college, a far cry from the public school curriculum of today, in which students are lucky if they even get a single year of Latin. However, in Shaw’s time, Latin was still considered an important part of learning any language, and at least at Dickinson, was required to some extent for every major. Another now antiquated requirement was that of religion classes. From its roots, Dickinson was a religiously affiliated institution, in which students were required to not only take Bible classes, but were also “required to attend Church twice on the Sabbath. The place of worship, however, [was] left to their own discretion, or that of their parents or guardians.”10 And, while these two lost elements of Dickinson life and study may seem unrelated, they share many surprising ties.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Christianity was still very prevalent even in secular life, and people sought biblical meaning even in pagan things, the Aeneid as only one example. While it is impossible that Vergil intended Aeneas to be a Christ-figure, many commentaries in the late 1800s and early 1900s attempt to some level to make this connection. As John Campbell Shairp, Professor of Poetry at Oxford, says in his 1881 book Aspects of Poetry,

There is in Virgil a vein of thought and sentiment more devout, more humane, more akin to the Christian, than is to be found in any other ancient poet, whether Greek or Roman. The religious feeling which Virgil preserved in his own heart is made the more conspicuous, when we remember amidst what almost overpowering difficulties it was that he preserved it.11

Henry Frieze echoes a similar sentiment in his 1902 commentary, saying in part that

[Aeneas] is intended to be the embodiment of the courage of an ancient hero, the justice of a paternal ruler, the mild humanity of a cultivated man living in an age of advanced civilization, the saintiness of the founder of a new religion of peace and pure observance, the affection of parent and child which was one of the strongest instincts in the Italian race. The strength required in such an instrument is the strength of faith, submission, patience, and endurance.12

While no one can be sure whether Frieze intended for his words to have a religious flavor, he describes Aeneas in a way that sounds eerily parallel to that of Jesus Christ, even mentioning a “new religion of peace” and that Aeneas was an “instrument of strength and faith.” Even if this was not his intention, it certainly highlights the extent to which academic thought of that period was steeped in Christianity. In fact, this view of the Classics continued up even into post- revolutionary America, in which Caroline Winterer claims that,

The Aeneid also offered boys lessons about heroism, imperial expansion, quasi-Christian virtue, and the stoic acceptance of fate. Although the lessons in the Aeneid were not inherently more applicable to republicanism than to monarchism, Americans during and after the revolutionary era applied its themes to their project of creating a republican, Christian nation.13

Thus, throughout early American history, ancient texts were read with an eye for modern religious and sometimes political parallels, as people were desperately attempting to make these epics fit the mold of their current lives, perhaps hoping to give their own experiences deeper meaning.

With this perspective of both Dickinson and early American religious climate, it becomes much easier to reconstruct what Esther Popel Shaw might have been taught in her classes with Professor Filler on the Aeneid and how she might have been pressed to interpret them. In the Greenough-Kittredge version that she likely used, while there is no specific Christ/Christian connection made, there is both a political and religious motive attributed to Vergil’s work. The introduction declares that the Aeneid “was not written merely as a work of art, nor from a casual poetic inspiration. It is the product of a patriotic national sentiment and a belief in the divine origin and destiny of the Roman State religion.”14 Once again, political and religious motive are associated with the text and, based off of the other commentaries of the time, it is likely that Shaw would have been pressed not only to see the work through a Christian worldview, but also to apply the Aeneid to her own political and religious surroundings and search for modern-day parallels.

Today, the dialogue has shifted away from religion and onto many different branches of academic thought. Some scholars are fascinated by the underlying political message of the work, attempting to examine the ways in which socialist and democratic nations interpret the Aeneid to fit their own political structures.15 Other scholars shift the focus onto Aeneas as a hero, attempting to justify his portrayal within the larger context of epic heroes.16 And still others, like Peter Jones, take a much more multifaceted approach, examining not only Aeneas as a hero, but also Vergil and his style and his possible motivations. Perhaps Jones’ most brilliant observation in his introduction is his comparison of Aeneas to a modern hero. He says that, “Aeneas is a man who must learn to submit to the will of the gods, a response wholly at odds with much of today’s ‘culture’ which insists that following the devices and desires of one’s own heart represents the very zenith of human achievement.”17 Not only is he perfectly witty, but he also makes an astute point about the dangers of trying to force Aeneas to fit any modern conception of what it means to be a hero. Aeneas is not from our time, and he is not meant to be. Instead of desperately trying to thrust him into a mold in which he simply does not belong, we must try to use him as a model of ancient values, always keeping him within the context he was meant. There are many qualities of Aeneas’, such as determination, passion, and patience, that are still very applicable to modern life; however, if we attempt to base his worth as a hero off of some sort of one-to-one comparison with the superheroes of today, he will fade into the background, utterly misunderstood.

So, to finally answer the question, “Why were people at this time reading the Aeneid?” I must turn to Professor Robert S. Conway’s lecture, which he delivered in 1931, on the bi-millennium of Vergil’s birth. His lecture, which was titled “Poetry and Government: A Study of the Power of Vergil” ends with a call to keep the Classics strong and alive for future generations. He says, “Let us see to it that our successors may have the privilege that has been given to us of hearing the great voices that older times speak in their own accents across the silent years, of being quickened by them to know the gold from the dross, of learning from them what is simple, what is high, what is human, what is true.”18 This answer not only answers why people in Shaw’s day read Vergil, but is also just as applicable to Latinists and Classicists today. Conway understands that if we lose the ability to understand the Classics, we also lose the ability to understand the past, to understand people who somehow saw the world through a clearer lens. To Conway, these are not merely stories but windows into truth and beauty and goodness. They teach us virtues even without our knowing, like that of hard work as we struggle through the Latin, and persistence as we try to peel back the layers of meaning in each word. Conway does not see Vergil as antiquated, but as timeless. Vergil’s words stand as pillars of truth as much today as they ever did, for he showed us through his bright words and gentle verse how to be brave, how to be patient, how to be weak, and most of all how to be truly, painfully human.

1. Doran, Malinda Triller. “Esther Popel Shaw (1896-1958).” Esther Popel Shaw (1896-1958) Dickinson College. 2013. Accessed April 05, 2017. http://archives.dickinson.edu/people/esther-popel-shaw-1896-1958.↩

2. “Courses of Study,” Catalogue of Dickinson College (1916-1917): 15. The Classical Course of study consisted of four hours of both Latin and Greek per week freshman year, and then an elective three hours per week for the rest of the course.↩

3. Doran, Malinda Triller. “Esther Popel Shaw (1896-1958).” Esther Popel Shaw (1896-

1958) Dickinson College. 2013. Accessed April 05, 2017. http://archives.dickinson.edu/people/esther-popel-shaw-1896-1958.↩

4. Ibid.↩

5. Ibid.↩

6. In a diary entry from Friday, June 19, 1914 she tells how her junior year report card had just come in the mail, specifically stating that she received a B in Virgil. Then again on Monday, September 28, 1914 she says that she “had a test in Greek History & rec’d a test paper in Latin in which I got a B.”↩

7. Esther Popel Shaw’s Alumni Questionnaire which she filled out in January of 1955.↩

8. Dickinson College Archives. “Mervin Grant Filler (1873-1931).” Mervin Grant Filler (1873-1931) Dickinson College. 2005. Accessed April 05, 2017. http://archives.dickinson.edu/people/mervin-grant-filler-1873-1931.↩

9. “Latin Language and Literature,” Catalogue of Dickinson College (1916-1917): 31.↩

10. “Public Worship,” Catalogue of Dickinson College (1834-1835): 14.↩

11. John Campbell Shairp, Aspects of poetry; being lectures delivered at Oxford (New

York, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1894), 140.↩

12. Virgil, Walter Dennison, and Henry Frieze, Virgil’s Aeneid. Books. I.-XII. (New York,

American Book Company, 1902), 21.↩

13.Caroline Winterer, “Why Did American Women Read the Aeneid,” in Blackwell

Companions to the Ancient World Series: A Companion to Vergil’s Aeneid and its

Tradition 2010, ed. Joseph Farrell and Michael C. J. Putnam (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-

Blackwell, 2010), 368.↩

14. Virgil, Walter Dennison, and Henry Frieze, Virgil’s Aeneid. Books. I.-XII. (New York,

American Book Company, 1902), 21. J.B. Greenough, and G.L. Kittredge, The Greater Poems of Virgil: Vol. 1, Aeneid I-VI.

(Boston, Ginn & Company, 1895), 34-35.↩

15. Ernst A. Schmidt, “The Meaning of Vergil’s “Aeneid:” American and German

Approaches,” Classical World 94 (2001), pp. 145-171.↩

16. Adam Parry, “The Two Voices of Virgil’s Aeneid,” Arion 2 (1963), pp. 66-80.↩

17. Peter Jones, Reading Virgil: Aeneid I and II. (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2011), 27.↩

18. Robert Seymour Conway, Makers of Europe (Cambridge, Harvard University Press,

1931), 83.↩