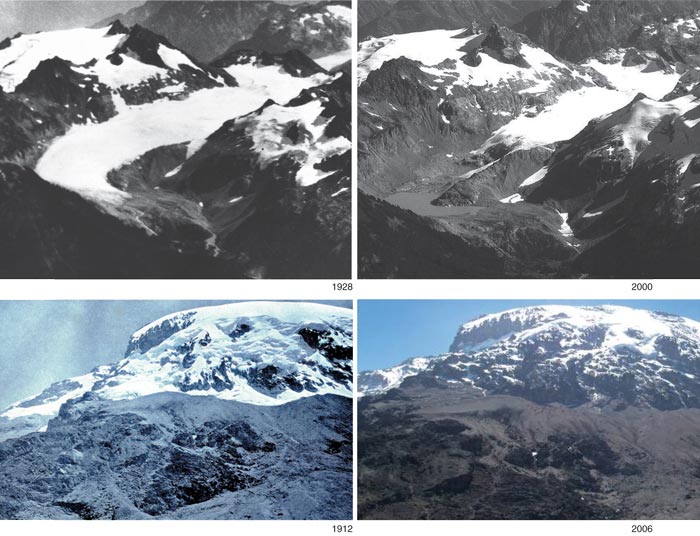

In places like Africa and more specifically areas around Mount Kilimanjaro the affects of global warming can already be felt. As this image clearly shows, the snow-covered mountain has recently lost large portions of its snow, due largely to global-warming.

This image above shows the effects global warming has had on Mount Kilimanjaro.

The snow on top of this mountain provides water to millions of Africans, and once it is gone these same people will be without access to freshwater. Because of situations like this in Africa and around the globe, it is critical that climate change policies address and stop the cause of this more recent problem: human beings wastefulness.

Controversy, however, still surrounds whether or not humans are the cause of global warming, which I intend to clear up. Within this debate a scientific consensus has already been reached that the source of carbon is human beings. The question is whether this increase in carbon (by human beings) is definitively causing climate change.

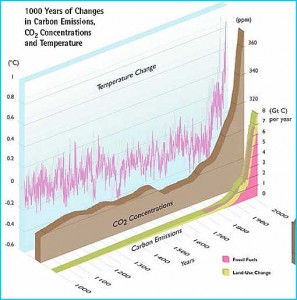

Science has concluded that without a greenhouse affect the Earth would be well below freezing. For this reason, ice & snow records along with tree rings show that a greenhouse affect and carbon gasses have always been present in the atmosphere. However, within the past century, particularly since the Industrial Revolution, it appears that carbon and greenhouse gas emissions have dramatically risen. For instance, since 1800 the atmospheric carbon dioxide has risen from 280 to over 370 parts per million. Because fossil-fuel utilization rates have been measured, it appears that their rates explain the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Moreover in the past it appears that atmospheric carbon dioxide rates were caused by the fact that Earth is naturally highly radioactive. It appears that since the Industrial Revolution, this radioactivity has declined. On account of the sources of this radioactivity, largely volcanoes and the deep ocean, losing their spark then the only logical connection is that fossil fuels are the cause of global warming. This information, along with fossil fuel utilization rates, implicates humans as a significant cause of the recent changes in CO2 emissions.

The question is what can we do at this point. Scientists have for decades been conducting research and presenting their findings, with limited to no success. This leads me to think a new approach is necessary for action to be taken.

This images from the BBC shows the faces of global warming and what will happen if immediate action is not taken.

Peter Singer, a Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, wrote “Famine, Affluence, and Morality” to describe the moral obligations shared by all humans. He states, “If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening…we ought morally to do it,” because he believes that most of the major problems in the world such as poverty and pollution are global issues. Applying this concept to global warming, because scientific evidence has not swayed policy makers to create stringent climate change policies then I would suggest we use images of the people will suffer most to sway policy makers. If we can’t do it for the Earth then lets at least make change for the people who will suffer if immediate action is not soon taken.

The consequences of climate change have ceased to be subtle.

In the past decade alone, we have witnessed dramatic weather-related events that scientists tie back to the rising concentration of CO2 in our atmosphere:

- In 2003, an unprecedented heat wave swept through Europe, killing over 35,000 people with the highest temperatures in centuries.

- An “epic” 6-year drought has dried up the Murray-Darling Basin, which provides nearly 85% of the water used for agriculture in Australia, forcing the Prime Minster to declare a ban on irrigation this coming summer.

- The melting rate of Pine Island Glacier on the West Antarctic Ice sheet has increased from 2cm/year to 1.6m/year since 1990. The current melting rate is more than 20 times faster than the melting rate the glacier maintained over the past 45,000 years.

Temperature change over the past millenium

These events are not caused by natural fluctuations of the Earth’s climate. The global climate does fluctuate due to the output of volcanic gasses and slight shifts in the planet’s axis of rotation, but the changes we have witnessed in the past two centuries deviate significantly from the natural variations. The detailed records we have taken over the past 150 years of the Earth’s surface temperature provide us with a good selection of data for comparison. As the graph shows, around the year 1850, the date of the Industrial Revolution, the concentration of CO2 in the air begins to climb dramatically, quickly and far exceeding the range of natural fluctuations observed between the years 1000-1800. While the temperature swung back and forth, prior to the 1800s, it stayed within about 1°C. Between 1850 and today, the temperature has rocket up an additional 0.5°C.

Additional evidence:

- Because our global economy is so reliant upon fossil fuels, we have a comprehensive record of how much coal, oil, and other resources we have used since the 1800s, which we can compare to the amount of CO2 intensity in the atmosphere. The levels are remarkably well correlated.

- The type of CO2 in the atmosphere also indicates that fossil fuels are to blame for this dramatic increase in global temperature. The most common Carbon isotope in the atmosphere today is not radioactive Carbon-14, or Carbon-13, but Carbon-12 which is derived from dead organic matter. Since fossil fuels are composed of dead organic matter, we can infer that the high concentration of CO2 in our atmosphere is related to fossil fuel consumption and not natural sources like volcanic emissions or deep-sea Carbon release.

- In the lab, scientists can only re-create our current climate situation when they include anthropogenic factors in their climate model simulations. Natural factors alone do not produce the conditions we are witnessing today.

Though it is not in the nature of the scientific community to report anything as “certain” or “proven,” the credible research completed in the past decade clearly and unanimously indicates that global warming has been greatly accelerated by human activities.

But let us be frank: determining who is to blame is only important for convincing skeptics of the severity of the challenges at hand. The most important facts to consider are the consequences we face, and our ability (or inability) to deal with them. As Table 1 illustrates, we have two possible interpretations and two possible responses – four possible resulting scenarios. If we are wrong and climate change is nothing but a bad scare, the worst that will happen is that we devote a lot of time, stress, and money to developing new technologies and preserving the natural world. But if we are right and if we do nothing, the consequences will be swift, extensive, and dire indeed. Are we, the great shapers of our habitat, going to leave that up to chance?

Table 1.

|

Climate change is real |

Climate change is not real |

|

| We make changes to massively reduce our impact on the climate |

1. Climate change is real + We react |

2. Climate change is not real + We react |

| We do nothing, continuing with our current lifestyle |

3. Climate change is real + We do nothing |

4. Climate change is not real + We do nothing |

(Mann, Michael E., and Kump, Lee R. Dire Predictions: Understanding Global Warming. New York: Daniel Kaveney, 2009.)

Tags: Australia, climate change, Drought, fossil fuels, heat wave, human-induced

The Amazon Rainforest – The Evils of Deforestation on Youtube

The Amazon Rainforest – The Evils of Deforestation on Youtube

Just because the hurdles are inevitable does not mean we cannot jump over them, so we must prepare ourselves to deal with them during the COP15 meeting in December 2009, in order to win the race against time and global warming. In “Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion” Whalley and Walsh describe these obstacles as something that will hinder the progress of negotiation, and will not lead to a satisfactory outcome. The first is the lack of a clear deadline. I agree with Whalley and Walsh on this issue because the vagueness of when goals need to be met is something that will in fact hinder progression and will take the focus off of other more important issues, such as Whalley and Walsh’s next point: unfulfilled commitments. What is the world to do with the unfulfilled commitments left over from the Kyoto Protocol? There are worries that these unfulfilled commitments will make countries more hesitant to ratifying a new agreement, because of the extra burden placed on actions they failed to take. I think we cannot just simply wipe these countries slates clean, but they must make up for what was lost, whether it is by more strict GHG restrictions, or more technology transfers. Based on the Whalley and Walsh article, another issue on the table is “the constraints from non-climate change issues”. This includes the challenges in interpreting the “common yet differentiated responsibilities” that will definitely be a big topic of discussion at this years COP15 meeting. Countries like China who has large portions of GHG emissions coming from manufacturing companies should not be fully accountable for the GHG emissions and should share the amount of GHG emitted with the countries these goods are traded with. I feel that yes, these issues are inevitable, but we must face them and collaborate as the human species, not as developing countries versus developed countries, because the longer we take to create a plan of action against global warming, the less effective we will be at combating and mitigating it.

Tags: China, climate change, COP15 Resources, Kyoto Protocol, Kyoto to Copenhagen, student-citizens

The first time I visited an American household I was appalled. I noticed that they left the lights on in rooms where there was no one, TVs were left on when no one was watching, and the central AC was blasting icy refrigerated air into every corner of the house.

As I soon discovered, this was not a one-family exception, but a sadly common practice among many American families, even if not always as extreme.

Growing up in Mexico, I was taught to always turn off the lights, fans, and other appliances when I wasn’t using them. To me, these were basic actions, as basic as flushing the toilet, and not doing so seemed unnatural. I just couldn’t understand why people would behave in such ways, not caring or even being aware of how wasteful they were being.

As time went by I understood: energy was cheap, and there was no conservation ethic.

In light of the threat of global climate change, these bad habits will have to change drastically, and they will have to change fast. Of course, people have to change their individual habits and make a concentrated effort to conserve energy on a daily basis.

But how to change habits that are so deeply ingrained in the system? It’s not just households that are wasteful: The best example of energy consumption in the U.S. comes from buildings. Specifically malls, shopping centers, and offices. The AC is blasted in the summer, the heater is raised to sweltering hot temperatures in the winter, lights are left on all night, and escalators are left running for hours on end. Changes have to be implemented everywhere, not just inside the home. There need to be structural adjustments in terms of how energy is consumed in public and corporate spaces as well.

Another huge problem: cars. Taking into consideration the America’s wide open spaces and that the main transportation infrastructure being roads, it’s hard to see a way around people driving everywhere. When most cars on the road are burning fossil fuels, the biggest issue becomes how to drastically improve this main source of GHG emissions.

One of the emission measures outlined in Whalley and Walsh’s report was “per capita”. While I think that the most important factor in reducing GHG emissions is people’s awareness as well as long term individual efforts, I do not think it is plausible to apply such a measure on a global scale. Out of all the measures I think it is the most ludicrous and difficult to implement.

First of all, how would these per-capita emission rates be calculated? Usually the calculation looks something like this:

Total GHG emissions for a country / Population of that country = Per capita GHG emissions

Yet not all citizens pollute at the same level. And how do we measure the emissions of corporations? Is it fair for a citizen to be burdened with the emission levels of a multinational corporation with which he/she has no relation?

This is not taking into consideration the most obvious bias: countries with large populations such as China and India would be off the hook. Because their population is so large, the per capita emissions will look deceivingly low, thus betraying the total amount of GHG emissions generated in the country as a whole, which is not negligible.

Another major problem: How do we decide what an “acceptable” per capita emission would be? The standard of living in each country varies wildly, and it is simply impossible to try to level them worldwide.

If we were to set the U.S. average per capita emission as an average, we would all choke in smog before the Earth’s temperature rose another degree. If, on the other hand, we set it at a lower level, say that of a developing country, everyone would be upset with that as well. The developing country wouldn’t have room to develop, and the developed country would have to un-develop or quickly change the whole set up of its infrastructure. Given the nature of existing systems and infrastructure, it is difficult enough to lower the levels of a country’s emissions, much more to lower *and* level them worldwide.

A note on how responsibility should be dealt in the case of GHG emissions in the manufacture of export goods in China, and any multinational corporation dealings in general:

While it is undoubtedly unfair to put the blame of GHG emissions produced while manufacturing products for export entirely on China, it is not possible to say that China holds no accountability for them either. As a trade agreement, it is only natural that both entities are benefiting, and they perceive themselves as benefiting. Therefore there should be a way for the responsibility for those GHG emissions to be split among the entities involved with the production of those products.

A video on algae fuel. It’s viability is debated, but it is interesting nonetheless:

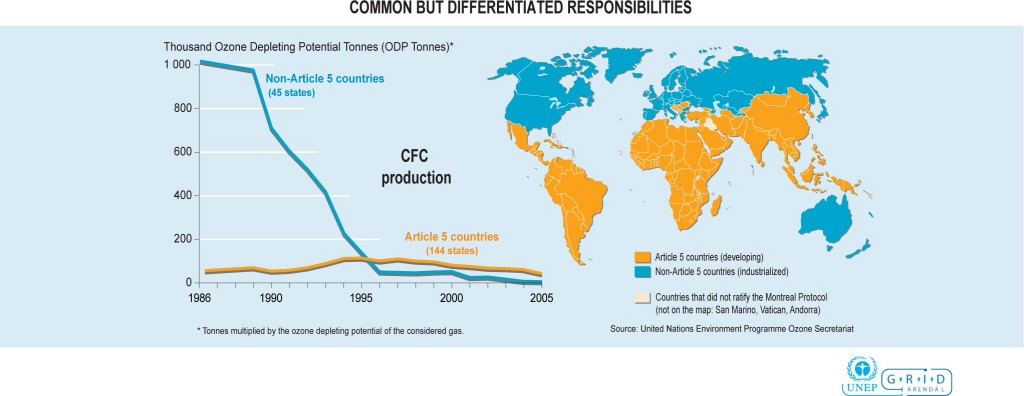

Maybe I’ve got it backwards (har har). I’ll be the first to admit that Climate Change is not my forte. As this class progresses and I am dealt the deed of being an ambassador for Dickinson College, I hope to wrap my mind around this larger phenomenon that will be taking place in Copenhagen. In Whalley’s Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion he speaks about “Common but Differentiated Responsibilities” as being the PARAMOUNT issue at hand. Since China, India, and Brazil are growing at such a rapid pace and desire to be affluent nations–they are going have to take on more responsibilities. However, smaller nations would not fall under the same umbrella. Understandable–why should a small country off the coast of Africa have to be under the same restrictions as say a country like China. However, does that make them free to go?

Below is a chart that is presented in the readings read last week in class in regards to which countries fall into specific categories.

(I apologize for the image size–it wants to fall off of the page otherwise. Here’s a link to view it fully–you may have to download it.)

Whalley presents two of the arguments:

– These countries should not be put under the same restrictions as the other countries as their primary concern should be the economic development and stability of the smaller nations.

– The other interpretation is to the form in which the commitment is undertaken–in which some countries would have one responsibility while others take on something else–so some would take on emissions intensity while others would take on emission levels.

To be honest, I haven’t made a complete decisions has to which interpretation I’m for–I suppose as I add to repertoire terminology and factoids I’ll be more inclined to plant my feet firmly in one. But I want to take the time to theorize the concept of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities on a college campus–particularly Dickinson’s. Perhaps with my minimal knowledge this is completely in left field. But here we go:

Dickinson College as a unit has certain responsibilities in order to be considered one of the Top 5 sustainable campuses in the country. The college as a body can limit certain things or change appliances to bring down our footprint.

Let’s say that our individual classes were smaller but still semi-prosperous countries. Classes have the responsibility to perhaps find alternative methods to printing out paper (such as Moodle, Blackboard) or perhaps even having a class go paperless ala the Amazon Kindle.

Now let’s go one step further and say that each individual student were even smaller, less prosperous countries. While we certainly would not be held to the same standards as Dickinson, or individual classes, we are still expected to do something rather than leaving it up to the college and individual classes/professors to do the work for us. Perhaps by doing simple things that Public Service Announcements would dictate such as turning off the lights when not in the room, not running the water when brushing your teeth, not driving from your dorm to the gym because of sheer laziness–things like that. Despite how simple they may be, they are responsibilities on a level which one could easily manage.

So we as a community have a goal of sustainability–but we contribute to it in different ways. Again, I want to stress this is not my finalized view of the argument, but, a way to perhaps to look it on a smaller scale.

Alright–after all of that–hopefully that makes some sense. I want to quickly jump to one more thing…

As a class tonight, we are watching The Age of Stupid. Check out the trailer and the link–I will be posting a supplementary blog entry to talk about my experiences with the film from both a climate change and Mass Media Studies perspective.

Tags: Amazon Kindle, common but differentiated responsibilities, COP15 Resources, Emission Intensity, Emission Level, The Age of Stupid

Your Comments