Despite never formally being a party of the UNFCCC proceedings, the United States has tremendous influence on the post-Kyoto negotiations leading up to COP-15 in Copenhagen this December. Many countries are looking to the U.S. to see if the change in administration can foster a greater involvement with new climate change mitigation after 2012 (the end of the Kyoto commitment period). Perhaps the most important country looking on is China, now the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gasses. For this reason and many more, China will be a focal point of the climate change negotiations for years to come.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon Urges China to Become Leader In Climate Change Fight

Tracing back to the refusal to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, the U.S. cited non-binding emission reduction commitments for developing countries as one of its main reasons. On the one hand China, India, and other developing countries were not the main contributors to the greenhouse gas emissions in pre-treaty industrialization period. On the other hand, this has certainly changed and any international plan to effectively combat climate change must include greater participation from these countries. While China seems to be willing to accept more responsibility, much has to be figured out as to what exactly that will entail.

Source: The Diplomat 28-Nov-2007

For instance, China has suggested that their reductions should be measured in terms of intensity rather than reduction of emission levels. By not setting a specified base date, this would allow the Chinese economy to continue to grow which would improve the living standards for its millions of poor. This perspective is shared among other countries with rapidly growing economies including India and Brazil. While the US and Europe acknowledge that it will take time for these countries to pursue overall emission reductions, other possibilities are being explored including establishing caps for specific industries.

China has also pointed out concerns regarding the liability for emissions reduction. A significant proportion of China’s carbon emissions (35%) are directly linked with exports. The argument here is that consuming nations, rather than manufacturing nations, should be held more responsible for carbon dioxide emissions. Complex calculations and concerns of implementation would inevitably arise if emissions were considered in terms of consumption rather than production. If this were to take place it could definitely slow down the process of reaching an agreement in Copenhagen. Nevertheless, this is an imperative issue for China as 60% of Chinese GDP stems from the manufacturing sector.

There are many issues to be resolved regarding China’s role (and the role of developing countries, more generally) in future climate change negotiations. The new U.S. administration should recognize China’s gaze on us to lead the way in making climate change a priority. After all, this is a global commons problem and greater participation from China is needed to effectively address the issue.

Tags: China, climate change, COP15 Resources, developing countries, Kyoto Protocol

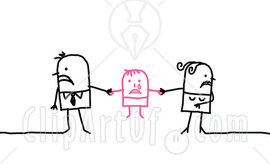

China and India have aligned on similar interests to take on Russia and the EU in a game of policy Tug O’ War. China and India are pulling for a per $GDP CO2 emissions reduction policy while Russia and the EU are pulling for an absolute quantity cap in CO2 emissions. But why this opposition? What is behind this game of Tug O’ War?

Negotiations for the post Kyoto Protocol period are looking into new possible greenhouse gas emission limits. The two that will I will discuss are an absolute quantity cap (like the Kyoto Protocol) and an emissions reduction per $GDP basis. In general, developing countries are lobbying for per $GDP emissions standards, while countries who have developed are lobbying for an absolute quantity cap. Although both very different, they share the common end goal of trying to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions to slow global warming (here’s a clip on global warming: Global Warming 101).

Per $GDP emissions reduction: Also known as emissions intensity, is a measure of the increase in emissions in comparison to the economic growth of a country. In order to lower ones emissions intensity, a country must invest in greener ways of developing. Developing countries such as Japan and China are for this approach to emissions reductions because it allows them to continue to develop without being hindered by emissions reduction caps.

This approach does not guarantee an overall emissions reduction, which is necessary to slow down global warming. Factors such as population and the total increase in GDP, which could reverse the efforts in cutting emissions, are not taken into account.

Absolute Quantity Cap: An absolute quantity cap requires a cap in total emissions. For example, the cap in total emissions for the Kyoto Protocol was at levels before 1990 emissions.

The EU is for a cap in emissions because they already cap their emissions through has a domestic cap-and-trade system (the EU ETS).

Russia is also for an absolute cap system similar to that of the Kyoto Protocol where the emissions where capped at 1990 levels. After 1990, Russia went into a severe economic downturn and their emissions were reduced dramatically compared to the levels of 1990. Therefore, an emissions cap at the year 1990 allows Russia to develop back to its previous state of economy without being held back by emissions reductions.

The absolute quantity cap does not take into account the differences in population for each country. Countries with more people, may find this method unfair.

In the upcoming conference in Copenhagen this December of ’09, it has been predicted that China and India, and the EU and Russia will be butting heads in negotiating the forms of mitigating emissions. Although they share a common goal, each seems to be holding on strong. The question is who will win this game of Policy Tug O’ War? or will the international community be able to find some common ground?

Tags: Grace Lange, Kyoto to Copenhagen, mitigation, sustainable development

Reaching a compromise at the Kyoto 2 Conference in Copenhagen on an agreement that will effectively address climate change in a manner that is sustainable, relatively equitable, and financially feasible will be extremely challenging. In the Bringing Copenhagen Climate Change to a Conclusion report, the authors elaborated on many potential problems for the upcoming conference that were not addressed in the Bali Cop13 Roadmap. However, the authors did not sufficiently address and critique the current understand of and financial provisions for conservation.

Reaching a compromise at the Kyoto 2 Conference in Copenhagen on an agreement that will effectively address climate change in a manner that is sustainable, relatively equitable, and financially feasible will be extremely challenging. In the Bringing Copenhagen Climate Change to a Conclusion report, the authors elaborated on many potential problems for the upcoming conference that were not addressed in the Bali Cop13 Roadmap. However, the authors did not sufficiently address and critique the current understand of and financial provisions for conservation.

There is a need for establishing stronger binding commitments to land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) issues within the Copenhagen conference rather than the vague Notes of importance, timid Requests for monitoring, voluntary Invitations to action, Acknowledgments, Affirmations, and other verbose and wimpy sentiments from pages 8-10 of the Bali Roadmap. LULUCF issues (particularly deforestation) are playing an enormous role in releasing green house gas emissions relative to many other sources (see here for GHG Emissions Diagram). The current Kyoto Protocol agreements are politely sidestepping these issues with impotent and inefficient incentives that encourage poor environmental practices, as is suggested in the Climate Challenge: Money on Trees documentary.

LULUCF issues (particularly deforestation) are playing an enormous role in releasing green house gas emissions relative to many other sources (see here for GHG Emissions Diagram). The current Kyoto Protocol agreements are politely sidestepping these issues with impotent and inefficient incentives that encourage poor environmental practices, as is suggested in the Climate Change REDD documentary.

There is a financial incentive for indigenous people to destroy existing primary and secondary forests and replace them with monocultural plantations, because they will not only receive carbon offset payments, but they will also make money from harvesting the biomass. This is not a sustainable trend. These tree plantations are often ecologically destructive as was described in Is Mother Earth a Cancer Patient? There is potential for incentivizing conservation. But, even if the Kyoto Protocol provides effective incentives there will need to be political paradigm shifts among local, regional, and national bodies as well in order for conservation programs to be effective as was described in the Brazil eyes Sugar Cane Ban. Additionally, defining LULUCF issues under the second pillar of adaptation mechanisms is too narrow a definition for such expansive problem. Conserving ecosystems, especially forests, are not just adaptive, but need to be viewed as important part of the mitigation pillar. There is potential for cooperation between developed and developing countries to work together on conservation programs like REDD programs that will not only sequester green house gases, but also contribute to preserving numerous threatened ecosystems (if they are properly managed, monitored, and organized). However, for programs to be successful there needs to be a larger percentage of the climate change budget to be diverted to these activities. According to the Navigating the Numbers: Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy Report, there is disproportionately small amount of funds diverted to the Adaptation fund relative to other areas. In order for conservation project to receive more funds it needs to be included in other parts of the Kyoto Protocol. It is potentially economically feasible for large amounts of carbon to be sequestered in many third world nations with the definitive financial and legislative support from developed countries (refer to the Potential Carbon Mitigation and Income in Developing Countries from Changes in Use and Management of Agricultural and Forest Lands report for more details. It should not only be part of the second pillar of adaptation, because this is too narrow a definition for such an enormous systemic problem. Conserving ecosystems, especially forests, is not just adaptive, but needs to be viewed as important preventive mitigation tool. Ultimately, the Bali Roadmap and the Bringing Copenhagen Climate Change to a Conclusion report both needed to give more attention to the issue of conservation. Hopefully, there will be a paradigm shift from a economically and techno-centered lens to also incorporate an ecological lens for parties at the Kyoto 2 Conference, so that there will be more provisions for this worthwhile and underappreciated cause.

This is not a sustainable trend. These tree plantations are often ecologically destructive as was described in Is Mother Earth a Cancer Patient? There is potential for incentivizing conservation. But, even if the Kyoto Protocol provides effective incentives there will need to be political paradigm shifts among local, regional, and national bodies as well in order for conservation programs to be effective as was described in the Brazil eyes Sugar Cane Ban. Additionally, defining LULUCF issues under the second pillar of adaptation mechanisms is too narrow a definition for such expansive problem. Conserving ecosystems, especially forests, are not just adaptive, but need to be viewed as important part of the mitigation pillar. There is potential for cooperation between developed and developing countries to work together on conservation programs like REDD programs that will not only sequester green house gases, but also contribute to preserving numerous threatened ecosystems (if they are properly managed, monitored, and organized). However, for programs to be successful there needs to be a larger percentage of the climate change budget to be diverted to these activities. According to the Navigating the Numbers: Greenhouse Gas Data and International Climate Policy Report, there is disproportionately small amount of funds diverted to the Adaptation fund relative to other areas. In order for conservation project to receive more funds it needs to be included in other parts of the Kyoto Protocol. It is potentially economically feasible for large amounts of carbon to be sequestered in many third world nations with the definitive financial and legislative support from developed countries (refer to the Potential Carbon Mitigation and Income in Developing Countries from Changes in Use and Management of Agricultural and Forest Lands report for more details. It should not only be part of the second pillar of adaptation, because this is too narrow a definition for such an enormous systemic problem. Conserving ecosystems, especially forests, is not just adaptive, but needs to be viewed as important preventive mitigation tool. Ultimately, the Bali Roadmap and the Bringing Copenhagen Climate Change to a Conclusion report both needed to give more attention to the issue of conservation. Hopefully, there will be a paradigm shift from a economically and techno-centered lens to also incorporate an ecological lens for parties at the Kyoto 2 Conference, so that there will be more provisions for this worthwhile and underappreciated cause.

Tags: Bali Roadmap, Clean Development Mechanism, LULUCF, Philip Rothrock

It is really interesting to see how big developing countries want to see United States’ actions on climate change first and then they will be following. But at the same time, United States is waiting to see what plans major developing countries will offer. India even challenged to the West by saying: “ You do the best you can, and we’ll match it.”

The strategy of taking “common yet differentiated responsibilities” was ill-defined in the early stage. Developing countries at that time were not able to commit any greenhouse gases reduction because development was the priority and it conflicted with being sustainable. So it was first interpreted as the OECD countries would take the burden of emissions reductions and there was no need for developing countries to participate in it. But as the earth is burning and so many catastrophies caused by climate change have happened, this is not the case any more.

In John Whalley and Sean Walsh’s article “Bring the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion”, they mentioned two different interpretations of “common yet differentiated responsibilities” that are prevailing now. One is that developing countries should receive financial compensation for taking commitments of emissions reductions. The other one is different countries take differential commitments between emissions intensity and emissions levels. The issue will be further discussed in the Copenhagen negotiation.

China and the climate change crisis

China and the climate change crisis 2

It is developing countries’ hope for “common yet differentiated responsibilities” to be effective. Without a doubt, developing countries need to make economic growth and to create a better standard of living for its people. The videos I embeded in the post are talking about China’s balance between economic development and the environmental crisis. China is one of the developing countries that have been developing very rapidly over the past decades. It is introduced in the interview that seventy percent of China’s industrial development depends on coal which contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. China is consuming energy at the rapid pace but it is rather difficult to control energy consumption when development is essential at the same time. However, this does not mean that China, or any other developing country, has not realized the seriousness of climate change. China has stated its position on the issue by expressing that “Any future arrangement on climate change should continue to follow the principles of common yet differentiated responsibilities established in the Convention, addressing climate change within the framework of sustainable development, equal treatment of mitigation and adaptation, and effectively solve the problem of financing and technology which the developing country parties are most concerned.” And this is probably the voice of all the developing countries.

Some developing countries are acused for having small amount of historical gases emissions compared with developed countries and low emissions per capita, and the fact of developed countries being the major contributor to climate change is neglected. This is not fair. The purpose for doing this is to give those developing countries more pressures so they would make commitments on emissions reduction. But by enforcing quantitative emissions reduction, it would limit developing countries’ development. Poverty results in rapid population growth which is one of the main factors that cause the environmental problems for developing countries.

It is interesting that in the report, the authors also discussed about liabilities of emissions reduction. In both the report and the videos, it is said that almost one third of China’s greenhouse gas emissions relate to exports. Whether this should be the liabilities of the countries that enjoy the final goods from the production is a question that needs to be further explored, but it is definitely not fair to blame it on China.

Up to this point, most of the nations have reached the consensus that the strategy of “common yet differentiated reponsibilities” should be taken, but the question now is how. I am hoping the answer will be found out during the Copenhagen negotiation this coming december.

Tags: China, climate change, Common yet differentiated responsibilities

As comments on my article Great Man Theory begin opening more questions, I find it increasingly necessary to respond with another post.

My largest concern with the ecological lens, which is argued for best on our blog by Philip Rothrock, is that global warming is not yet seen by enough people to be a pressing issue.

My best possible analogy is to abortion:

The argument in abortion debates, in my mind, relates to Aristotle’s Metaphysics:

Potency refers to the ability of a virtual reality (in this case a woman is impregnated) to become actualized – a baby is born.

The argument is: when does potency become actualized?

The argument against abortion then, is that actualization occurs at the moment of conception: that abortion is always murder because the child will be born unless we interfere.

It doesn’t take a prophet to recognize that fertilization will produce a child; we don’t need to see the woman’s round belly to know that she is having a baby. It has happened countless times.

Yet human-caused global warming has never occurred before… so how do we prove the Earth is pregnant?

The pregnancy test exists – we know that parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere have risen 35% since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. And increases in GHGs are the corpus delicti of fertilization.

But what will it take to prove to Americans that their spending habits need to change? Increases in CO2 certainly aren’t convincing enough (especially because so many are convinced that scientists still argue about the effects of CO2).

My answer in previous posts has been greener technological advancement, which Philip has argued is short-sighted, but Whalley and Walsh have argued is the long term solution (259).

So who is right? Both, really. The term argument (from A Rulebook for Arguments) is defined as “a set of reasons or evidence in support of a conclusion” (xi). One does not necessarily defeat the other, but I believe Philip’s argument is misworded.

The conclusions of Philip’s argument aren’t that technological advance is short-sighted: advancement in green technology does lead to long-term payoff; the true conclusions are that we need to change our habits of excessive expenditure. And Philip is right. No single approach will reach the numbers we need in CO2 – we need to do everything we can to combat global warming.

But in keeping with my original argument: convincing people to consume less for ecological reasons is easier said than done.

So change the argument. The Bali Roadmap, which in part outlines the methods of developing greener technologies, “calls for the creation of incentives” (Whalley 259). So why not incentives on the individual level? Why not give people the desire to spend less?

In this video interview with Bill McKibben , the naturalist argues that the number of Americans who said they were very happy peaked in 1956 and has gone steadily downhill since then. How could this be? When our affluence has steadily risen?

McKibben offers that friendships make people happier than “a bunch more stuff out in the storage locker on the edge of town” and that our desire to by houses on remote plots of land distances us from the community that neighbors bring.

McKibben argues that stuff doesn’t make people happy. And if we could convince people that their happiness relies on friendships rather than material possessions, we might be on the track that Philip proposed.

And Philip’s track does make the process easier. It puts less demand on the need for technological change.

And though we may have trouble convincing people that the world is pregnant, perhaps we could convince them that spending simply isn’t making them happy.

Works Cited:

Weston, Anthony. Rulebook for Arguments. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2009. Print.

Whalley, John and Sean Walsh. Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion. CESifo Economic Studies, Vol. 55, 2/2009.

ead all articles by Brett Shollenberger on this blog!

Read articles by Brett Shollenberger in Dickinson Magazine!

Read Brett Shollenberger‘s blog!

Your Comments