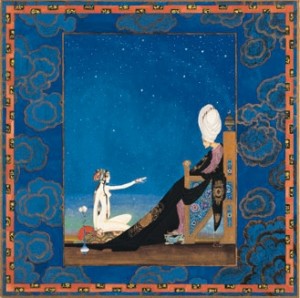

The well-known myth of Scheherazade reflects the ultimate use of storytelling as a mechanism of survival. Trapped in the King’s castle, the young Scheherazade tells stories throughout the night, ending each narrative at the break of dawn. The King, in an eagerness to hear the stories continued the next night, spares the life of Scheherazade, enabling her to continue to live through storytelling. Among the queer community, survival is a constant challenge (Sedgwick, p.3). To tell the stories of those who have survived queerness, is ultimately to give them life. Furthermore, it gives life to all those who are exposed to the story by providing a concrete alternative, a pathway, (Halberstam, p.2) a potentiality for a future (Munoz, p.1) a story through which all those queer (and not queer) can vicariously live through. In fact, queer space has been defined as the development of such “alternative temporalities”; a space that has the “potential to open up new life narratives” (Halberstam, p.2). In this sense, queer space may be conceptualized as the very stories, novels, accounts and archives of the queer among us.

Through the theoretical lens of queer space as a potential for new narratives and a reflection of life itself, it becomes possible to understand Shani Mootoo’s novel, Cereus Blooms at Night as a powerful example of storytelling for survival. The protagonist, Tyler, insists that recounting Mala Ramchandin’s story (and the story of those of her time and space) fulfills a particular duty: his “intention to relate Mala Ramchandin’s story” (Mootoo, p.15). In fact, Tyler’s “shared queerness” (Mootoo, p. 48) with Mala enables him to find life in her narrative, to explore the possibility and the layers of queerness through the consistent unconventionalism. If queer space can be expressed as the “potentiality of life unscripted by the conventions of family, inheritance, and child rearing” (Halberstam, p.2), then the Ramchandin chronicles provide a stark opposition to heteronormativity. Moreover, Halberstam’s language, namely the word “unscripted” serves to highlight the value of narrative and the written word in creating this queer space. To some extent, the very care Tyler provides for Mala is characterized by the retelling of her life – the narrative itself is what keeps Mala living. Novels of queer identity then, or more broadly, queer stories provide an essential source of life. In the context of words and the romanticization of survival stories, even queer loves become eternal: as Tyler’s fascination for the gardener Mr.Hector grows, be begins to characterize him as “ageless” (p.70), emphasizing the sheer endlessness of queer that only narratives provide.

While Cereus Blooms at Night, among many other written and not-written stories, serves as a queer space, heteronormative institutions that have silenced and suppressed queerness (Sedgwick, p.2) are what ultimately ‘kills’ queers. In combination with the “systematic separation of children from queer adults” (Sedgwick, p.2), the erasing of queer voices and thus queer lives remains a critical threat. What is really needed then, are the stories of the queer: LGBT archives provide a wealth of narratives that serves to give life to individuals who have been violently quieted throughout history. Storytelling as survival, coined by the legend of Sheherazade is easily found among many distant disciplines. In the field of clinical psychology for example, it is well-known among eating disorder researchers that one of the most beneficial interventions is for recovered individuals to tell their story to those who are ill. Why? Because to hear about the possibility of a future, when your diagnosis inherently rejects living, is to provide motivation, to provide a model – narratives then, are a path amidst thick woods: a way.