Utopia and Buzz Killers

My head hurts… but I think I get it now.

In reading Munoz and comparing his arguments with the queer theories of Leo

Bersani he alluded to in his piece, I think I now understand the point he is making.

Munoz begins with “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality.” explaining that it is something that is evolving. It is on the horizon for those who follow behind today’s LBGTQ activists and theorists to identify and determine what it’s future will be. What we know in this place and time is evolving, and what it will become, the future will determine.

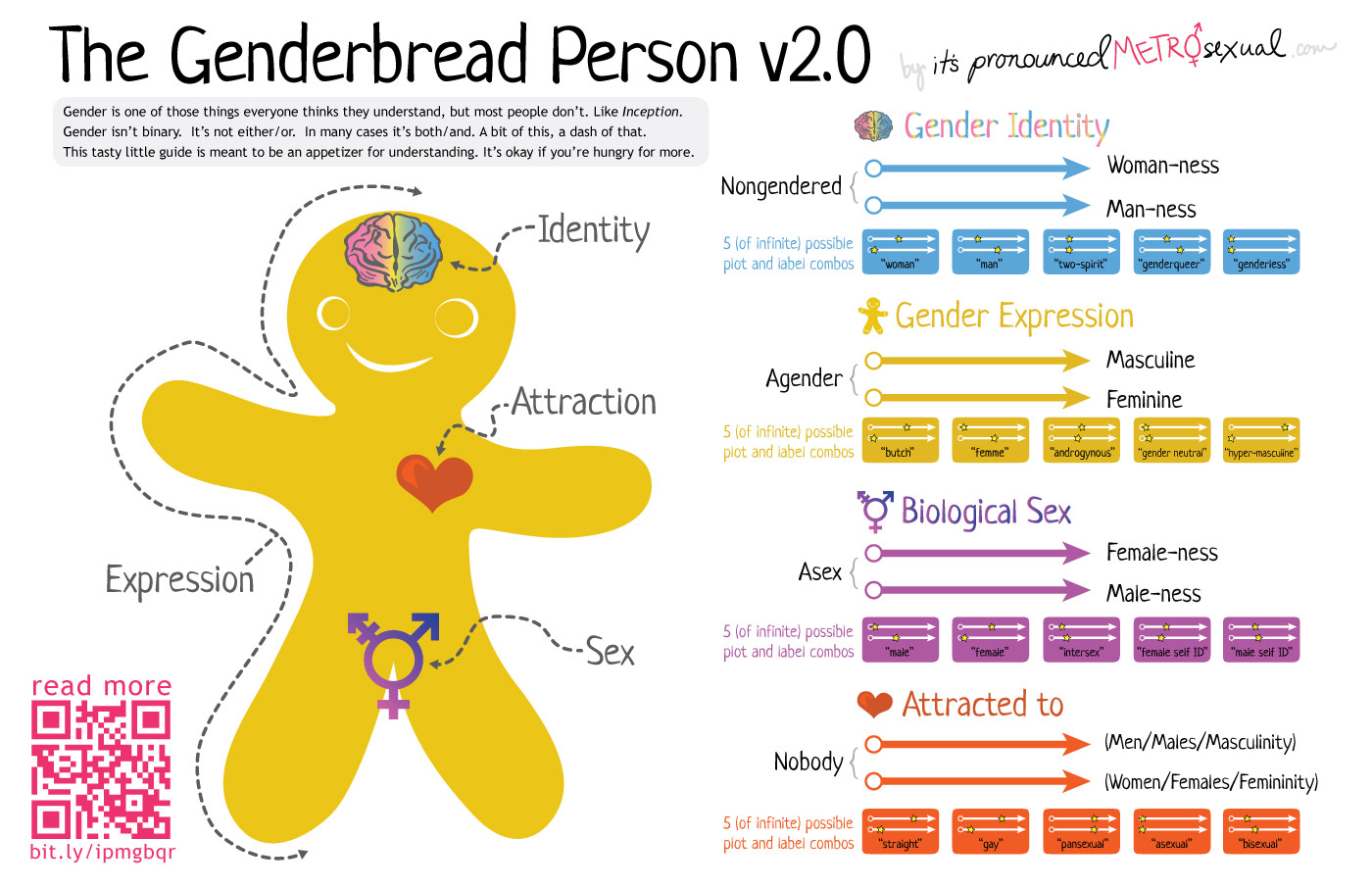

Leo Bersani’s book, Homos, Munoz explains, tells us of a world that now exists where queerness has become mainstream. The Gay Rights movement wanted America to listen and accept the civil liberties and rights of all those in the LGBT community, and America did to some extent. There are primetime sit-coms depicting LGBT families and daytime talk show hosts that are openly gay, making it seem that America accepts and supports the inclusion of all people. Gay icons in the arts, fashion, broadcast media, politics and intelligentsia are embraced by all but the extreme right, but still homophobia prevails. But why and by whom? Is it, as Bersani suggests, that some “anti-social queer theorists” wish to distance themselves from anything normative and mainstream and are gay-image-homophobic? Is social acceptance forcing a group identity on people that are so diverse in every possible sense of gender/biology/sexuality/emotionality that feels just as oppressive as exclusion, therefore causing a pushback in the strata of gender and queer philosophers and theorists? Did the invisibility of the previous counterculture provide a kind of security from public visibility to those who wish to remain out of the spotlight? Or does antirelationality serve to avoid labeling identities that can be fluid and transient, ever evolving as we ourselves evolve and reinvent our realities. Nevertheless, the antirelationality arguments fueled Munoz’s position that some theorist’s view this as a perversion of uncontaminated sexuality.

My ah-ha moment came at the bottom of page 11, in Munoz’s last 2 sentences. Leading up to those last words, he says that queerness is something still out on the horizon, still out of reach, and that it has little to do with our present and contemporary view of gay identity. “My argument is therefore interested in critiquing the ontological certitude that I understand to be partnered with the politics of presentist and pragmatic contemporary gay identity. This mode of ontological certitude is often represented through a narration of disappearance and negativity that boils down to another game of fort-da.”

He compares it to a child’s game of “Fort-Da!” which Freud first reported while observing a young toddler in the home of a family he was visiting. The young child had a close and nurturing relationship with the mother, and when the mother left the child for a bit, the child would play calmly with an object, throwing it into some corner or under a piece of furniture, exclaiming “fort!” the German word for gone. The child would then look to retrieve it calling out “da!”, meaning here it is!, delighted when he found it. This self-invented child’s game served to reassure the child that good things do materialize, like his mommy.

A Queer Utopia may well be “da” in a promising future.