In Feeling Utopia, the reader is introduced to the idea that queerness, as a utopia, does not exist yet, and if it ever does, it will not be in our lifetime. It’s a “warm illumination of a horizon,” “a longing that propels us onward,” a “doing for and toward the future,” and a “rejection of a here and now” (Munoz). I think the most important idea here is the fact that the simple act of being queer– the fact that you are a queer person who exists– means you are actively rejecting the present and all the structures that come with it. By just existing, you are living in the future. Because all the queer people that came before us never existed in a queer utopia, and therefore neither do we. We can build on our past and progress, but we are always going to be reaching toward that horizon– crossing the open space between what we know and what we try to know.

We borrow from the past and we propel ourselves into a future that we know will be better. Celine Sciamma, the director of Portrait of a Lady on Fire, said that “You still have to tell the story. You can’t quote. Not yet” (Sciamma). She is referring to the fact that the history of queer culture is often so fragmented (she uses Sappho’s poetry as an example) that we cannot draw on it as a simple fact but rather with memory and filling in the blanks with our own experiences. Time then, circles back around as we see ourselves in the past figures who saw themselves in our future.

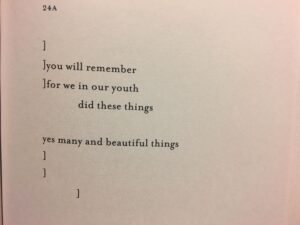

To work toward this idea of a queer utopia does not mean there are specific actions or ways to be queer. Existing and remembering does the trick. “Someone will remember us / I say / even in another time” (Sappho fragment 147). This fragment is all we have left of what might have been a longer poem, or something that means something else entirely. It refers to a future time and the writer is certain that she will be remembered, and she turns out to be right, because we are reading her words thousands of years later. Yes, they have been transcribed and translated many times over, and reinterpreted. Author’s intent is pretty much impossible to distinguish. But that means we get to decide what it means for us individually and as a community, because there’s possibility in her words and so there’s possibility in ours too.

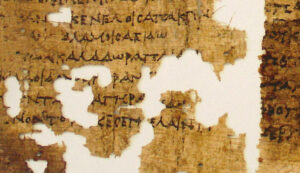

sappho’s poetry fragments (written down, not as she would have performed/perhaps wrote them):

a sappho poetry fragment, as translated by anne carson with the brackets showing where words might go:

the interview excerpt and link to the article:

Our culture is at the stage of memories. It’s not at the stage of history,” Sciamma told me, in an early conversation. The historical record is so incomplete that it has to be supplemented, even supplanted, by remembered stories. “You still have to tell the story. You can’t quote. Not yet.” She added, “That’s lesbian culture. Sorry.” Gesturing with a cigarette, she emphasized the second syllable in a French-sounding way that made it clear she wasn’t sorry. Then she quoted Sappho’s Fragment 147: “someone will remember us / I say / even in another time.”

“Someone,” she emphasized. “Not ‘this country,’ not ‘poetry,’ not ‘literature.’ Someone.”