Not sure what a foodway is? Learn more about this food studies term here!

Dickinson College Food Studies Certificate Program

Not sure what a foodway is? Learn more about this food studies term here!

Walking into The Hamilton Restaurant is like getting a warm hug from Carlisle’s history—except this hug comes with chili, mustard, and a lot of diced onions. As the self-proclaimed “Home of the Hot-Chee Dog,” The Hamilton has its status far beyond your one-stop place to grab lunch, it’s a local legend with a side of fries.

Our class visit felt like a backstage pass to the soul of Carlisle. We sat down with Thomas Mazias, the 81-year-old owner who took us on a verbal stroll down memory lane. Starting as a dishwasher at 11 years old after fleeing war-torn Greece, Thomas now runs Carlisle’s oldest restaurant with the passion of someone who knows that what they’re serving is tradition and a sense of comfort from the laid-back approach to cooking signature to small-town diner.

The Immigrant Narrative and Resilience

Caraveo, J. (2021, April 8). Photo of Thomas Mazias at The Hamilton Restaurant [Photograph]. Local21 News. https://local21news.com/news/proudly-pennsylvanian/proudly-pa-how-a-carlisle-restaurant-owner-went-from-dishwasher-to-boss

The enduring popularity of the Hot-Chee Dog demonstrates how food can become a localized symbol of identity. Holtzman, among many food studies scholars have pointed out how food acts as a cultural mediator, embodying community values and shared experiences (Holtzman, 2006). For Carlisle residents, the Hot-Chee Dog is a ritual that links them to the town’s history and each other. Whether it’s lawyers on lunch breaks or college students nursing a case of the late-night munchies, everyone who visits The Hamilton partakes in a collective tradition.

PandaBytes. (2016, January 8). Photo of Hamilton’s Hot-Chee Dog [Photograph]. PandaBytes. https://pandabytes.blogspot.com/2016/01/hamilton-restaurant.html

Visiting Hamilton provided a vivid example of how food studies intersect with themes of identity, community, and migration. The restaurant embodies a deep sense of tradition while grappling with the challenges of remaining relevant in an ever-changing culinary landscape.

Photo courtesy of Helen Van

One of the ways Hamilton has adapted is by working with Warrington Farms, a local butcher, to maintain a short food supply chain (T. Mazias, personal communication, November 26, 2024). This partnership not only ensures the quality of their ingredients but also aligns with the rising emphasis on environmental sustainability in the food system. By sourcing locally, Hamilton reduces its carbon footprint while supporting another small business in the community—a reflection of the interconnectedness of local economies and sustainable practices.

However, the balancing act between nostalgia and innovation is ongoing. On one hand, Hamilton’s charm lies in its old-school simplicity, with its no-frills menu and consistent offerings. On the other hand, adapting to modern consumer habits is essential for survival. For example, the restaurant still operates as cash-only, a relic of a bygone era. But change is on the horizon: Thomas’s nephew is planning to install card payment systems, a nod to the increasing reliance on digital transactions.

References:

Holtzman, J. D. (2006). Food and Memory. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, 361–378. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25064929

Dickinson College. (n.d.). Where did all the Greeks go? The Hamilton Restaurant: Home of the Hot-Chee Dog. Retrieved November 26, 2024, from https://blogs.dickinson.edu/carlislehistory/where-did-all-the-greeks-go-the-hamilton-restaurant-home-of-the-hot-chee-dog/

Interested in the science behind the art of fermentation? Check this out!

The Dickinson College dining services are one of the most common ways for students to access meals. However, most students have not had a chance to learn more of the finances revolving around the dining hall, not until Dickinson’s Intro to Food Studies Class got a behind the scenes look at the cafeteria.

Finances are extremely important when it comes to dining services. Having enough money determines what dining services can or cannot produce and the quality of the food they produce. The most well-known way the cafeteria makes money is through students swipes that are associated with their meal plan. However, various people do not know where the money from their swipes go to if they are not used. The answer is: back to the students (S. Wright, Personal Communication, November 21, 2024). Dickinson’s Assistant Director of Dining Services, Sonya Wright explained how the money people do not spend through their swipes ends up being returned to the college’s general fund. Dining Services alone makes about $10-11 million dollars per fiscal year with $5-7 million in profit. This surplus is given back to the college to be reinvested in addressing campus needs, as well as improving the Dickinson student experience.

Sonya Wright In the Dining Hall. Photo courtesy of K. Trogner.

As finances are to be utilized properly, the cafeteria staff also wishes for students to enjoy their meals. This is done by staff, chefs, and other employees in dining service listening to what the students prefer to eat (S. Wright, Personal Communication, November 21, 2024). Executive Chef of dining services Ashlee Telep explained Dickinson College’s menus are thoughtfully designed to consider what students want to eat and the menu for each semester is created over a two-month period (A. Telep, Personal Communication, November 21, 2024).

Ashley Mowreader (2024) from Inside Higher Ed also explains “Students believe having a wide variety of nutritionally balanced food is most important in their food selection, followed by a variety allergen-friendly foods, accommodations for different dietary needs and foods that satisfy religious needs”. Maintaining high variety and quality dining services allows for students to thrive both physically and mentally. Dickinson’s various dining options shine in the cafeteria alone: it offers multiple options such as a pasta bar, a gluten free section, a vegan and kosher section, a salad bar, and various other choices. Additionally dining services works to create thousands of portions of these different types of food per day in order to feed students, allocating proper proportions for each meal in order to make sure there is enough food for everyone (S. Wright, Personal Communication, November 21, 2024). Overall, the dining services menu is thoroughly planned in order to help ensure students have a delightful experience in the dining hall.

Behind the Scenes in the Dickinson College Kitchen. Photo courtesy of K. Trogner

Works Cited

Mowreader, A. M. (2024, January 17). Survey: Students Value Choice in Campus Dining Facilities. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved November 21, 2024, from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/student-success/health-wellness/2024/01/17/what-college-students-want-their-dining-provider

When I first saw the topic of “Food Ethics”, I immediately thought of the treatment of the animals that are being used for their resources. In my opinion, it is morally right to make sure that the animals being used for their resources are treated in the best way possible. A lot of people choose to not eat meat because they believe that meat eating involves painful suffering to the animals that are killed for food. When someone decides not to eat meat for that reason, then they are being ethical ( Food Ethics Council, 2023).

I personally do not eat meat because I care about the wellbeing of animals and the environment. I feel like I am being ethically responsible. A question that I found interesting in an article by the Food Ethics Council (2024) is “what makes a choice ethical?” The Council goes on to state that an ethical choice is one that is defined by our values and our principles(Food Ethics Council, 2023). Another question that I thought of was “how do our food choices reflect our personal values.” For example, someone might consume a plant-based diet which may reflect their personal values of being sustainable, caring for animals and bettering their health. I think that those are important questions to ask because everyone might have different definitions of being ethical.

https://fisher.osu.edu/blogs/leadreadtoday/measuring-value-ethics-business

As there are a lot of unethical labor practices, I think that consumers should boycott the companies that enforce those unethical practices. For example, the small salary that workers gain from working long, intense hours should be juxtaposed with the prices we pay for those products since not even half of what consumers pay gets put into the workers’ pockets ( Food Ethics Council, 2023).

Another way that food can be ethical is by reducing food waste. The reduction of food waste betters the environment by decreasing the production of greenhouse gasses (Johns Hopkins, 2024). Saving food also means saving money and possibly saving other families in need. In a world where food waste is reduced, I wonder how different it would be. Would there be bigger families due to the reliability of no food waste aka no hunger? There would be a significant decrease of greenhouse gasses emitted which would improve life just a little. I think that this hypothetical situation would extend the life of Earth as the resources would be more conserved and less energy would be used. We as a society need to make more mindful choices in our food waste and diet to see a significant change in the world.

Works Cited

Food Ethics Council. (2023, March 29). What is food ethics? https://www.foodethicscouncil.org/food-ethics/what-is-food-ethics/.

Food Ethics Council. (2024) Fair and Resilient Food Systems. https://www.foodethicscouncil.org/food-ethics/what-is-food-ethics/.

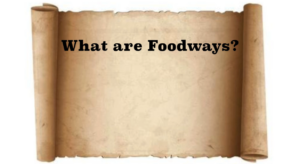

Our reading for this class, “Fat Wars”, chapter nine of Shilpa Ravella’s book, A Silent Fire: The Story of Inflammation, Diet, and Disease (2022) repeatedly used normative words to describe foods and their chemical contents. I find the most illustrative example to be on page 162 when Ravella (2022) describes the fats found in Crisco as “insidious”.

Photo courtesy of pikpng.com

This book was published in 2022, so it is not old by any means. It exists in the modern context of how we discuss food; the discussion has not largely changed since then and should be held to the same standards that we hold ourselves to now. It is my personal opinion that we as an American society have moved past this sort of conversation and the language it uses. I thought we had started talking about how we can use this knowledge about types of foods and the compounds within them to make healthier choices while still enjoying the food we eat and participating in our native foodways. The idea that one foodway is morally superior to another is a dangerous rhetoric that I strongly object to.

In the same vein, Ravella (2022) poses the populations in the Seven Countries Study that have lower rates of heart disease as sort of protagonists in the ‘fat wars’ she describes. In doing this, she is perpetuating the stereotype that American consumers are unintelligent (the ‘Dumb American’) and are unable to make healthy choices for themselves (Ravella, 2022). When field experts like Ravella stop treating the American public with indignity, we may learn and grow together as a nation but until then we will continue to operate under the strain of health moralism.

Further, Ravella holds an MD and is a gastroenterologist. She interacts with patients who are experiencing symptoms and who come to her vulnerably. As a chronically ill person, I find it worrisome that she speaks this way about the relationship between our bodies and food. It places an element of blame on her patients and on chronically ill people for their suffering which is told to us constantly writ large and that I maintain does not belong in healthcare.

I would like to contrast all of this with Professor Christine O’Neill’s presentation which covered many of the same concepts. She focused on putting words we all know from daily life into an understandable scientific context. She brought terminology from the lab back into the kitchen by using these terms to break down ingredients commonly used in American cooking such as butter. Prof. O’Neill did all this while maintaining a friendly professionalism that encouraged curiosity and student interaction. She was able to demonstrate that it is not only possible but beneficial to approach this topic with an attitude of good faith and I applaud Prof. O’Neill for her ability to do so.

Works Cited:

Ravella, S. (2022). A Silent Fire. W.W. Norton & Company.

Many cultures have their own food that walked alongside them through history, and later evolved, just as Kimchi was made for only Koreans and now is eaten by people globally. As food advanced throughout the years it has been built into society, and dishes became intertwined into one’s culture. Popular dishes such as kimchi can be individualized to different families liking as well as their own recipe. There are about 200 variations of kimchi. Different and famous variations of kimchi in Korea include:

(https://www.foodnetwork.com/recipes/food-network-kitchen/baechu-kimchi-11281091)

2. kkakdugi kimchi made from Korean radish

(https://www.koreanbapsang.com/kkakdugi-cubed-radish-kimchi/)

3. chonggak kimchi made from ponytail Radish

(https://www.maangchi.com/recipe/chonggak-kimchi)

4. dongchimi kimchi, a type of watery (mul) kimchi usually consumed as soup in winter.

(https://www.maangchi.com/recipe/dongchimi)

Baechu kimchi is the most consumed kimchi in Korea (Surya & Nugroho, 2023). Despite its popularity, other people may eat other kimchi. Some like to let their kimchi ferment for a few days to a week, two weeks, or even for months. It does not entirely matter how long it sits since kimchi is made using live culture called lactic acid bacteria (LAB) which produce organic acids that help with the unique flavor of kimchi. Not only does kimchi have a unique flavor it also is great for the stomach and has many benefits for nutrients and antioxidants. (Surya & Nugroho, 2023). When looking to buy kimchi it is recommended to look for it in the refrigerated area since this indicates live cultures present in the ferment (J.Halpin, personal communication, November 6, 2024).

Throughout history, Koreans discovered that salted and seasoned vegetables, beans, seafood, and other foods remained edible, and also developed a specific taste after being left in earthenware jars for a certain period. Common seasonings used for making kimchi are garlic, ginger, radish, carrot, green onion, fermented seafood (jeotgal) and red chili powder (gochugaru). The tradition of making kimchi with family has been formed through a long history and includes common attitudes, beliefs, and practices unique to the community.

In a way this tradition reminds me of the way my family makes Tamales, a Mexican dish that takes a whole day to make and cook. Although Tamales are not fermented, the process requires a lot of work, time, and patience. They are made from corn that’s filled with any type of meat commonly used is pork, beef, and chicken, and also contain spices as well, such as cumin seeds, chili powder, jalapeño, and salt. They are wrapped in banana, and or plantain leaf and left on the stove for 1-3 hours to steam. This process of making tamales compares with the way kimchi is made and processed because of the time, and high effort put into making the dish.

As we discussed in class, Kimchi is a traditional dish that has been passed down by many generations, is part of one’s identity, and culture and will be done in many ways. It will always be a comfort food for those who are connected to kimchi dish.

Works Cited:

Surya, R., & Nugroho, D. (2023). Kimchi throughout millennia: A narrative review on the early and modern history of Kimchi. Journal of Ethnic Foods, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-023-00171-w

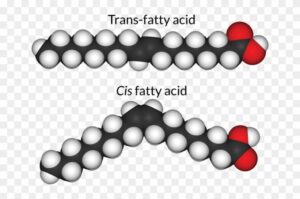

The food we eat every day is not just food for ourselves but also for trillions of microorganisms that live inside of us. These microorganisms live primarily within the gut and can weigh up to six pounds. For a part of the body that large, it has gone mostly unseen and unnoticed. However, the new field of study of the microbiome shows links that impact everything from the immune system to Parkinson’s and infections.

The microorganisms that live inside our microbiome differ between each and every one of us and is influenced by something as simple as a vaginal birth or C-section birth. The earliest part of the baby’s life is the most important in the establishment of the microbiome, as the organisms that are transferred to the baby will last the rest of their lives. Mother’s milk compared to formula is also seen as the healthier option for the baby and establishment of a healthy microbiome (M. Rauhut, personal communication, October 31, 2024). The best way to support the health of your gut microbiome is to have what is described as a traditional diet, high in carbohydrates and fiber (M. Rauhut, personal communication, October 31, 2024). This diet lets the microorganisms produce a wide variety of micronutrients that our bodies would be unable to create otherwise. Having a diet high in animal protein and sugars can lead to an increase in unhealthy and unhelpful microorganisms (M. Rauhut, personal communication, October 31, 2024).

“Large Intestine, Illustration – Stock Image – C027/7483.” Science Photo Library. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/703782/view/large-intestine-illustration.

A critical component of the microbiome and its microorganisms is how they have been proven to affect other parts of the body. New studies have shown that some common infections can be cured by transplanting a healthy microbiome into a sick person’s gut. This is accomplished through a fecal transplant procedure. However, this operation has also been seen to transfer someone’s anxiety or depression to the recipient, proving that mental health is deeply connected to the gut. Many of the neurotransmitters that are used in the brain are created in the gut, and these transmitters can create the feelings of stress and happiness that all experience day to day. The immune system is also connected, as it controls what passes into the body, and when the immune system has been compromised for too long it can lead to inflammation, which in turn can lead to depression and Alzheimer’s (Robertson, 2023).

“What Is the Gut-Brain Connection? – Life First.” What Is The Gut-Brain Connection? – Life First. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.lifefirstassessment.com.au/blog/2020/june/what-is-the-gut-brain-connection/

The gut microbiome has proven to be one of the most understudied organs in the human body. New developments are happening all the time. Just a few months ago a new study came out that shows that intermittent fasting can actually help promote a healthy microbiome (M. Rauhut, personal communication, October 31, 2024).

References:

Robertson, Ruairi. “The Gut-Brain Connection: How It Works and the Role of Nutrition.” Healthline, August 20, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/gut-brain-connection.

Click here to learn more!

© 2025 Food Studies Academic Technology services: GIS | Media Center | Language Exchange

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑