Throughout the semester, we have focused on a variety of perspectives and understandings of food and food studies. Rather than looking at food through a scientific or cultural lens, today’s class with Professor Adrienne Su focused on the incorporation of food as a theme in her art. Professor Su is a poet and professor of creative writing with five published books of poetry (Poetry Foundation, n.d.). She came to our class to discuss how food has “infiltrated her poetry” (A. Su, personal communication, December 5, 2024). As a creative writing minor, I was curious to see what Professor Su was going to discuss in class. I do a lot of creative writing in my spare time, but almost none of it is poetry and, prior to today’s class, I thought none of it was about food.

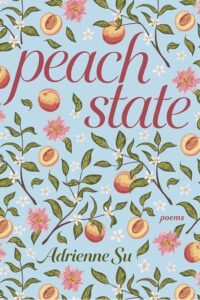

Image: The cover of Professor Su’s book of poetry Peach State, which features the poem Lychee Express. Food is a central theme in this book of poetry, exemplified by the title, which identifies Georgia as the “peach state” and the imagery of fruit on the cover. Image sourced from: University of Pittsburgh Press. (2019, March). Peach State. University of Pittsburgh. https://upittpress.org/books/9780822966562/

Food, as it is one of the most basic elements of human life, integrates itself into almost every aspect of our daily lives, including into our stories. Professor Su was gracious enough to show us the process of writing one of her poems, Lychee Express, during class. She described the inspirations behind the poem as a part of her desire to go through ordinary life “imagining the journey of fruits at the grocery store” (A. Su, personal communication, December 5, 2024). She also led the class through a ten-minute writing exercise where we used phrases from our oral history podcast assignment to free write prose or a poem and then discussed it.

Professor Su’s writing incorporates a great deal of what we have learned so far this semester. In her writing, she draws connection between food and her own history, her identity, and world history, with a particular emphasis on experiences from her daily life (Poetry Foundation, n.d.). As we discussed in class, Professor Su uses food to discuss historical comparisons and social/societal norms in Lychee Express (Poetry Foundation, 2019).

As I reflected on Professor Su’s use of food in poetry, I began to think about food as a theme in my own writing. In general, my fiction writing stems from a similar place to Professor Su’s talk: imagining a journey, process, or archetype that already exists in my life or in history, then expanding on it or imagining a different reality for it. Like Professor Su’s journey of grocery store fruits, my writing, which is often set in fictional worlds, usually incorporates food to explain the conditions of the world to the reader. Learning about Professor Su’s process, and how she thinks about food and poetry, led to the realization that food is a significant theme in my own writing. Professor Su’s talk emphasized how dynamic and important the field of food studies is, in that it is so often incorporated into art.

Works Cited:

Poetry Foundation (n.d.). Adrienne Su. Poetry Magazine. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/adrienne-su

Poetry Foundation. (2019, January). Lychee Express. Poetry Magazine. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/148684/lychee-express