A Truly Nuclear Life: Growing Up as a Woman in 1950s Utah

By: Olivia Whittaker

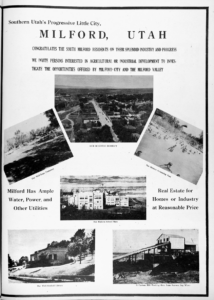

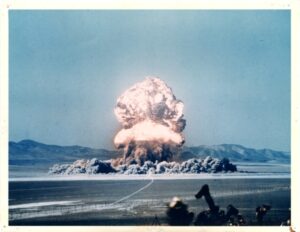

On January 27, 1951, residents of Milford, Utah and others first stood outside to watch the brilliant white flash of a one-kiloton bomb fill the western sky. It was the first atomic bomb test of the Nevada test site, around 250 miles away. They watched for a moment in awe what would soon become routine to the rugged little railroad town.

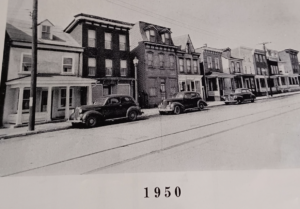

In his book American Dreams, H.W. Brands characterizes 1950s America as an age of new technology, consumerism, and middle-class prosperity. He paints a picture of American suburbia where men work, women tend to homes and children, and families enjoy car vacations, football games, and TV dinners.[1] While not inaccurate, Brands’ overview is general and limited. There are several critical aspects of American life in the 1950s that he omits, such as the instrumental roles of gender, religion, and nuclear threat. Examining the experience of one Iola Whittaker, a teenaged girl living in the small Mormon town of Milford, Utah in the 1950s, provides specific insight into these facets of life not meaningfully explored by Brands, revealing the more complex, and sometimes darker reality of nuclear life in the western United States.

Nevada Test Site bomb test, circa 1960s. Courtesy of Oregon State Special Collections &; Archives Research Center

Wind from the West, Storm from the East

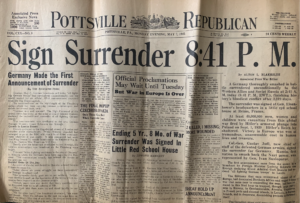

In the late 1950s, the National Election Study found that about 73% of Americans trusted the government— more than three times the current level.[2] Americans of this decade were faithful that their leaders would act in their best interests, and most took the government at its word. So, when the United States Atomic Energy Commission promised safety to the public as they began testing atomic bombs in Nevada in 1951, the public believed them. From 1951 to 1992, the commission would run 100 atmospheric atomic bomb tests that could be seen hundreds of miles out, including by Milford. “There would just be absolute white-out in the atmosphere,” Iola recalls.[3] She even describes how residents would “go out and sit on [their] porches” to watch the big flash. They knew when the tests would occur, as the times would be announced in the newspaper or on the radio in advance.

What wasn’t mentioned, though, was that the wind would carry radiation out east to towns like Milford, putting potential millions at risk of thyroid disorders, genetic mutations, respiratory diseases, infertility, and life-threatening cancers.[4] Not only was the Atomic Energy Commission aware of the danger years in advance, but actively lied in their press releases, ignored the cautions of scientists and researchers, and even forced their own scientists to falsify field reports to deny any adverse effects of the tests on nearby livestock, which had suffered countless burns, malformations, and fatalities.[5] “They just didn’t tell us what their research was showing,” Iola says, “and in the meantime, people were starting to get sick.”[6]

But to the commission, this was simply the cost of communist containment. The importance of bomb testing was stressed throughout the government. In a 1956 issue of Milford News, Utah representative Henry Dixon was quoted saying: “We cannot jeopardize our present commanding lead by halting tests so vital to the development of modern weapons without being absolutely sure that the Soviets would do like-wise,” in response to one congressman’s proposal to halt testing as a “prelude to disarmament.”[7]

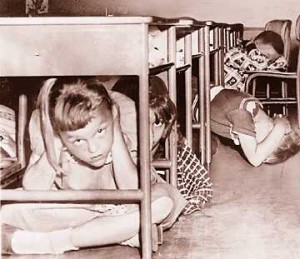

Cold War anxiety cast a continuous shadow over even the sunniest of American suburbia. On Saturday mornings, Iola and her family listened to the radio program I Was a Communist for the FBI, which emphasized the danger that communism posed to the United States. In school, Iola and her classmates participated in regular “Duck and Cover” drills, where students practiced taking cover under their desks in case of Soviet bombing. But while Cold War fears were more tangible to adults (who paid attention to politics), children didn’t seem to pay them much mind. “Kids kind of gloss[ed] it over,”[8] Iola says. She compares the bomb drills to fire drills, routine and mundane. Though she does recall a chilling moment in March of 1953, when she discovered that the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had died: “I remember being in eighth grade … the only thought I had [was]: ‘Oh my God, could there be something worse coming’?”[9]

Nice and Quiet Girls

Despite 1950s America being distinct for its stark gender roles (think: the endlessly parodied “1950’s housewife”), Brands’ American Dreams lacks attention to the experiences of women and the impact of gender norms throughout the decade. Even though Iola was often comfortable with a more traditional lifestyle, cultural ideas about gender critically shaped her life and environment growing up. The influences could be silent, as with the activities and subjects she was pushed towards in school; and when it came to issues of sex and even domestic violence in her town, it was less about what was said or done, and more about what wasn’t.

Iola had never noticed gender disparities in her early childhood. “We were kids outside playing in those early years.” she says, “…some of my best friends were the boys that I had grown up with.”[10] But as she entered high school in 1954, that was about to change. She could no longer play alongside her male peers, as gym classes were segregated by gender, and girls were barred from several of the sports enjoyed by boys. She describes this as her “first questioning,” saying: “As girls, we started to question, you know: ‘well, how come at school we can’t do track?’”[11]

As it was generally assumed that girls would one day become homemakers, the school prioritized teaching them skills like cooking and basic sewing— all girls at Iola’s school were required to take home economics classes. Iola hated them. She found the classes confusing and had no interest in sewing (or wearing) aprons; but as a girl, there was simply no way out of it. So, she put her head down and did the work she had to do. The highly gendered culture of Iola’s school and town was a product of its time to be sure, but it was especially informed by the Mormon church. “They set the religious code,” she says.

Sexual abstinence was a major part of that code. Iola remembers that “health [class] was always taught by the football coach… and believe me, you did not learn very much in health, especially you never learned anything about women’s health.” Menstruation “couldn’t even be mentioned,” and “abstinence was… pretty much the first sentence of any speech.”[12] Topics of sex, sexuality, or even reproductive health were taboo, and silenced within the Mormon culture. But as some women in Milford knew, that silence could come at a grave cost.

As a child, Iola wasn’t aware of the abuse occurring in other girls’ homes. She recalls about one girl who was younger than her: “we thought gosh, she’d have bruises on her, [but] never, never even thought about that her father was an abuser. And he was, but nobody turned him in.” As she got older, she realized that there were several men in her town who abused their wives and daughters. “Other men knew it,”[13] she says, but they said nothing. In her later teen years, Iola “started to put two and two together.” She confronted her father, saying: “How dare you men not… do something about this???” But this only angered him. “This is just the way the world is,” he replied dismissively.[14]

The Mormon Way

The Mormon church would not protect women against sexual abuse, but in the late 1950s, it began to concern itself with a different kind of “sexual deviancy.” In 1958, Bruce R. McConkie published Mormon Doctrine, the first general authority-authored book to explicitly condemn homosexuality. McConkie placed homosexuality among “Lucifer’s chief means of leading us to hell,” along with other such offenses as rape and infidelity.[15] The book was widely received as representing the official stance of the church, even if it was not actually endorsed by it. Of the more religious people in town, Iola says that “…they felt like [homosexuality] was a mortal sin, that it could be corrected, and that people should work hard in having it corrected.” Though she herself disavowed this belief, saying: “The sin of it was that people acted so awful about it.”[16] There were a few gay people in her life, including friends of her aunt and even a high school classmate. “We never worried about it,” she says. Iola and her family didn’t think one way or another about queer people, but their feelings were not shared by the whole community.

Iola was always an outlier in her religious town. Unlike almost everyone else, she never believed in the Mormon doctrine. She describes religious differences as a “topic of contention” in Milford.[17] Her peers were often discomforted when they found out that she didn’t share their beliefs. Iola even remembers some people acting confused that her and her sisters were so nice despite not being Mormon. But Iola always found the church’s teachings difficult to believe, and found the many religious superstitions people held especially irritating. In one anecdote, she remembers working on a sewing project when a girl told her: “You know every stitch that you take on a Sunday is like…putting the nails in Jesus.”[18] And it wasn’t just Milford that was saturated in LDS Ideology—when Iola’s sister, Thea, moved with her husband to just outside of Salt Lake City, their town kept a list of homes that were not Mormon, which Iola characterizes as “discrimination.”[19]

What She Wants

Being non-religious was not the only way in which Iola pushed what was expected of her. When she became a young adult, her father wanted her to enter secretarial training, as was common for women. But Iola wasn’t interested in secretarial work. As she put it: “I didn’t want to just go sit at a desk and take stenography…And my dad was encouraging me to do that because he was of that “old white men knew better” sort of [ideal]. And so if you wanted to have a woman have employment, they were either teachers, nurses, or stenographers.”[20] Instead, Iola wanted to go to college, but it took some convincing to get her father on board. “He probably took a deep breath,” says Iola, “he was probably talking to my mom who would talk to her sister that was in the town that had the college, and they convinced dad that, ‘okay, you know, she can do this.’”[21]

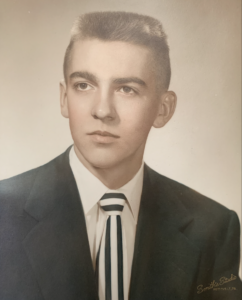

Iola Whittaker (Then: Iola Young) in Snow College yearbook, 1960. Courtesy of Snow College Digital Collections

But although she took control of her future by pursuing an education, Iola never considered herself a feminist. To her, the feminist movement occurred in big cities. It was women challenging the status quo by breaking into fields like law, marching in the streets, and taking political action. Iola respected those women and considered them brave, but she mostly only saw them on television, and only when she was older, during and after college. “It was not a movement in Utah,” she says.[22] And besides, like most women in her environment, Iola married in college and dropped out to support her husband. She had kids and worked as a secretary in his department while he completed his graduate program. But Iola was happy. She loved her husband and kids and wanted to support them. “You know, I really have to say I think we worked together,” she says, “You know, it wasn’t like: ‘oh gosh, Mack, I wish…we were making more money’ or things like that. That was not our prime target… I wanted the marriage, I wanted the children, I knew what I was going to have to do, you know, to make a life for all of us, and it was okay at that point.”[23] By a more modern view, Iola could easily be considered a feminist simply by building the life she truly wanted for herself and by respecting the rights of other women to do the same.

While H.W. Brands portrays the 1950s as an era of prosperity, consumerism, and traditional family life, the lived experience of Iola Whittaker tells a more complex story. Her life in Milford, Utah—shaped by nuclear fallout, gender roles, and an oppressive religious culture—exposes gaps in and expands upon Brands’ description. Iola’s unique perspective reveals a side of 1950s America that Brands’ broad narrative overlooks.

[1] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2010), 70, 80.

[2] “Public Trust in Government: 1958–2024,” Pew Research Center, accessed May 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/.

[3] Iola Whittaker, interview by Olivia Whittaker, Zoom, April 25, 2025.

[4] “Decoding Downwinders Syndrome: Effects of Radiation Exposure,” Downwinders, published September 9, 2023, Decoding Downwinders Syndrome: Effects of Radiation Exposure – National Cancer Benefits Center – Downwinders.

[5] Janet Burton Seegmiller, “Nuclear Testing and the Downwinders,” History to Go (Utah Division of State History), n.d., accessed May 2025, https://historytogo.utah.gov/downwinders/.

[6] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[7] “Dixon Says U.S. Can’t Risk Halt on Bomb Tests,” Milford News, November 1, 1956, in Utah Digital Newspapers, accessed May 2025, newspapers.lib.utah.edu.

[8] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[9] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[10] Iola Whittaker, interview by Olivia Whittaker, Zoom, April 12, 2025.

[11] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[12] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[13] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[14] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[15] Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine (Bookcraft, 1958), 639, Mormon Doctrine : Bookcraft Inc : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

[16] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[17] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[18] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[19] Iola Whittaker, additional information over text message to Olivia Whittaker, April 25, 2025.

[20] Whittaker, interview, April 25, 2025.

[21] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[22] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

[23] Whittaker, interview, April 12, 2025.

Interviews

- Zoom call, Carlisle, PA, April 12, 2o25

- Zoom call, Carlisle, PA, April 25, 2025

Full Transcript from First Interview