The Summer of Love?

By Jack Hentschel

During a lunch break in the summer of 1967, a friend and coworker of Jack Hentschel suggested they visit his alma mater, the University of California, Berkeley. They left San Francisco’s Financial District and eventually arrived at the campus, where they made their way through a maze of card tables in front of Sproul Hall, protesting everything from the FBI to Christianity. Then they entered the friend’s former frat house. “There, in the lounge, at high noon, on a couch,” recalls Jack, “was a demonstration of what the Summer of Love was all about, as a couple of lovers were in the act of “how to do it,” without shame.” Though the lovers seemed to be having fun, Jack was not impressed.[1] Neither were many Americans in the summer of 1967—or, to the hippies of San Francisco, the “Summer of Love.” In the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of the city, young people engaged in casual sex, listened to psychedelic rock, recited avant-garde poetry, preached peace and love, and consumed all kinds of drugs, all summer long. But soon enough, the drugs became pricey, the camaraderie caused overcrowding, and peace and love turned to violence as dealers gunned each other down in the street. H.W. Brands, in his book American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, writes that the Summer of Love “proved to be a letdown, as was probably inevitable.”[2] Thanks to his experience in the Bay Area throughout the Sixties and Seventies, Jack Hentschel would tend to agree. Though it began as a genuine movement of nonviolence and self-expression, the Summer of Love quickly deteriorated into the very thing it preached against.

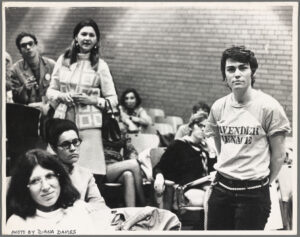

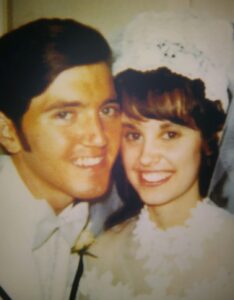

Jack Hentschel first moved to San Francisco in 1961. There, he met Mary Muldoon, and during the couple’s brief stay back east, she became Mary Hentschel. In 1964, the Hentschels returned to the city with a baby boy. They bought a house in the suburb of Walnut Creek the following year, and another boy followed the year after that. Jack lived in the Bay Area and worked in San Francisco’s Financial District until 1979, when he and his family moved again to his home state of Connecticut. He saw the rise and fall of the hippies at their nexus.[3] When exactly they began to rise, though, is hard to determine. Jeremy Guida, in his article “The Summer of Love Wasn’t All Peace and Hippies,” claims that the idea of a hippie was “defined by the media more than anything else.”[4] The hippies evolved from a related, yet distinct group in San Francisco called the beatniks, who protested the social conformity of postwar America. Hippies originally consisted of artistic, younger adults more politically minded than the beatniks—and more interested in drugs and rock and roll.[5] Even in its early years, the subculture was not relegated to San Francisco—it popped up in parts of New York, Chicago, and Seattle—but that is where it flourished, especially in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Integral to its development was the January 1967 “Human Be-In” in Golden Gate Park, a combination of peace rally, music festival, and poetry recitation.[6] Thanks to the success of the event, the hippies declared the summer of 1967 to be the “Summer of Love.” When fall rolled around, the parks grew chilly, and the school-aged hippies returned to their studies. The subculture would continue to thrive in certain pockets of the country for the remainder of the decade, but it never again reached the heights of the summer of 1967.

For Jack Hentschel, the story of the hippies starts with his move to San Francisco. Initially, they constituted only one part of the city’s general vibrancy. He recalls that “in the first apartment we had, not far from the Golden Gate Park and the H-A district, it was like living in a United Nations compound. English was not the first language for many.”[7] A few teenagers having sex and smoking pot, therefore, garnered neither a strong reaction nor any specific attention from him. “For the most part,” he says, “before hard drugs took control of the movement, I viewed them as harmless, entertaining and in many ways refreshing from the norm.”[8] Caught in the generational gap between the hippies and their frustrated parents, he could relate, and not relate, to both. He admired the hippie desire for freedom, independence, and self-expression. And thanks to his childhood, “molded by parents of the Depression and the WW2 experience, I had tremendous respect for authority and doing what was right.”[9] When he himself became a father, he found it easier to side for parental control. He especially disliked the drug use, even in the movement’s early stages, when it was relegated to marijuana: “I nearly got lung cancer from ingesting secondhand pot smoke from parties that we attended.”[10] Pot smoke was not the only thing in the air. In addition to new drugs, the hippie movement also introduced new forms of music to the American people—a lot of which, like psychedelic rock, was inspired by drugs. Of this, too, Jack was not a fan: “The noise from the Stones and the Dead never found a place on our tape recorder.” But it found a place on their sons’.[11]

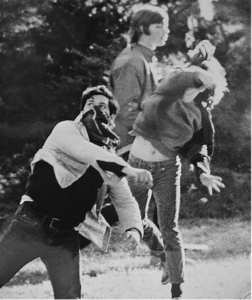

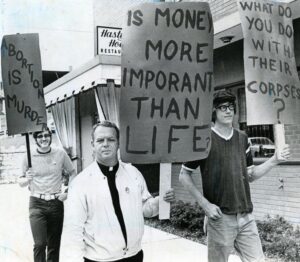

As the movement progressed and politicized, Jack’s disagreements with the hippies became more a matter of ideology than taste. Like the hippies, he loathed the Vietnam War, but he also “was not in favor of large-scale and anti-USA demonstrations,” which is how he viewed the peace rally aspect of the Human Be-In.[12] And though the Be-In sparked a Summer of Love for the hippies, to Jack, it was just another summer: “1967 was much like any other ‘60s year to us, and the Summer of Love had no particular impact on us.”[13] But the concept fueled itself, and by June, the brand-new Monterey International Pop Festival was netting an attendance of 75,000.[14] It launched the careers of unknowns like Janis Joplin and the (aptly named) Who and provided rockstars, like Jimi Hendrix, their biggest venue yet. Jack pitied those in the crowd: “My observation was that the movement was co-opted by the slick and greedy shysters in the music industry and that, in reality, the flower children became victims of those who were in it only to make a very large and easy payday.”[15] Pity turned to active dislike with the introduction of hard drugs like cocaine, methamphetamines, and LSD, which brought even more hippies to The Haight and increased gang violence: “As the movement advanced in numbers and notoriety and members of one protest group became commingled with others in parallel groups, overall chaos on the street became more apparent.”[16] And while the Summer of Love eventually ended, its effects reverberate today. In her article “The Long Summer of Love,” Zoë Corbyn argues that “because so many countercultural practices have become mainstream, they are difficult to see.”[17] The hippies not only popularized yoga, meditation, and vegetarianism, but also political movements like environmentalism and sexual liberation. Jack believes that many of the domestic issues America currently faces can “trace their roots to the permissiveness that led to the hippie movement and its egocentric mind set.”[18] So much for peace and love.

H.W. Brands is right to call the Summer of Love a “letdown.”[19] Moderate Americans like Jack Hentschel, though they could sometimes find fault with the indulgences of the hippie lifestyle, were not its primary victims. The hippies themselves faced the consequences for their overlong party. They were the ones who lived in the crowded Haight, or who blew their money on thrills, or who became addicted to meth. Along the way, the hippies championed noble causes like anti-consumerism and protesting the Vietnam War. But any coherent message was lost as the protests turned into drug-fueled orgies, and the hippies’ insatiable appetites brought gun violence onto the streets. When Jack entered his friend’s old frat house at Berkeley, the lovers were not alone. At the base of the couch lay a large, sleeping dog. “The sleeping pooch could only have been symbolic of the general public,” Jack muses, “ourselves included, that ignored the raging chaos that was all around us.”[20]

[1] Email interview with John Hentschel, April 19, 2023.

[2] H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 148.

[3] Hentschel.

[4] Jeremy Guida, “The Summer of Love Wasn’t All Peace and Hippies – JSTOR DAILY.” JSTOR, https://daily.jstor.org/the-summer-of-love-wasnt-all-peace-and-hippies/.

[5] Jill D’Alessandro et al., Summer of Love: Art, Fashion, and Rock and Roll (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2017), 20. [Google Books]

[6] Brands, 146-147.

[7] Hentschel.

[8] Hentschel.

[9] Hentschel.

[10] Hentschel.

[11] Hentschel.

[12] Hentschel.

[13] Hentschel.

[14] Russell Duncan, “The Summer of Love and Protest,” De Gruyter, https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/transcript.9783839422168.144/html.

[15] Hentschel.

[16] Hentschel.

[17] Zoë Corbyn, “The Long Summer of Love,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-long-summer-of-love/.

[18] Hentschel.

[19] Brands, 148.

[20] Hentschel.

Appendix

“The summer of love that followed proved to be a letdown, as was probably inevitable.” (H.W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945, p. 148)

Interview Subject

John ‘Jack’ Hentschel, age 87, who lived in the Bay Area and worked in San Francisco from 1964 to 1979

Interviews

- Email, April 19, 2023

Selected Transcript

From email:

Q. When did you first become aware of the emerging “hippie” subculture? What were your initial thoughts on it?

A. San Francisco in the ’60s was a very vibrant and fun place to live and work. In many respects, counterculture was the culture, therefore there were many faces and identities, some welcoming, some not. I recall that in the first apartment we had, not far from Golden Gate Park and the H-A district, it was like living in a United Nations compound. English was not the first language for many. The way life was, it just seemed that the flower children were part of the fabric and that their “Thing” was just one of many different things that made up the City. Initial reaction therefore was “live and let live.” They were as much part of the landscape as the fog horns we heard daily.

Q. You became a father to two boys in the 1960s. Did you feel allegiance to any group in the “hippie debate”? Did you align more with the young people or their frustrated parents?

A. Generally speaking, I was a half-generation older than the average hippie and a half-generation younger than their parents, so I could relate to both in many ways. I found the hippie desire for freedom, self-expression and independence something I could embrace. However, being a child molded by parents of the Depression and the WW2 experience, I had tremendous respect for authority and doing what was “right.” Therefore, disappointing my parents was the last thing I could consciously do. Score one for parental control.

Q. San Francisco was seen as the “hippie Mecca.” How visible were hippies in your day-to-day life in San Francisco? Was there a marked difference between your experience in San Francisco and in other parts of the country?

A. Being centered in the Haight-Ashbury and the western part of town, the enclave was several miles from the Financial District where I spent eight hours a day. Occasionally we would see a few at a time on the streets, but as a group, we rarely encountered them. For the most part, before hard drugs took control of the movement, I viewed them as harmless, entertaining and in many ways refreshing from the norm.

Q. The hippie subculture was defined in large part by its association with illegal substances. Did you ever encounter drug use during your time in San Francisco? Did you ever partake? What were your thoughts on it?

A. Early on, smoking a little pot, 24-hour sex, protesting the war (draft), plucking a guitar, dressing in funny clothes and listening to heavy metal music defined the movement. As things developed, it was the open use of and effect of hard drugs (thank you Timothy Leary and LSD) that most people associated with the hippie lifestyle and which ultimately was the cause for its downfall. Grammy and I are probably the only two people of that era who, not once, experimented with any drug use. That is not to say that we weren’t aware of its existence. Pot was openly in use everywhere. I nearly got lung cancer from ingesting secondhand pot smoke from parties that we attended.

Q. The hippie movement brought new forms of music to the American people. What were your reactions to bands like the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane? Did your children become fans?

A. Peter, Paul and Mary signing “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” was as much as I could handle from the music world. The noise from the Stones and the Dead never found a place on our tape recorder. I know that your father and Uncle John were much bigger fans of rock than we were.

Q. In January 1967 the hippies moved from Haight-Ashbury to Golden Gate Park, where they staged “the first human be-in.” Do you recall this event, or the presence of hippies in San Francisco’s public parks? What were your thoughts on the Vietnam War, which the be-in protested?

A. I’m aware of the human be-in event and vaguely remember that it received a positive reaction in the mainstream press, as did much of the hippie movement. I thought the war was a monumental mistake and couldn’t understand why our government was supporting a nation and people who, for the most part, were not eager to defend themselves. Having said that, I was not in favor of large-scale and anti-USA demonstrations. Anything anti-USA was not and is not in my DNA.

Q. The hippies declared the summer of 1967 to be the “Summer of Love.” Did the hippie subculture in San Francisco become more visible to you that summer? How was the Haight affected? Did you notice an increase in visitors to the city?

A. I had a friend who was proud of his degree from Berkeley and suggested we visit the campus one day during our lunch break. After negotiating our way through a maze of card tables set up in front of Sproul Hall protesting everything from the FBI (J. Edgar Hoover “The PIG”) to “Christianity Is a Fraud,” we paid a visit to my friend’s frat house (I think SAE). There, in the lounge, at high noon, on a coach was a demonstration of what the Summer of Love was all about, as a couple of lovers were in the act of “how to do it,” without shame. My friend, who was straighter then straight, was not a happy camper. 1967 was much like any other ’60s year to us, and the Summer of Love had no particular impact on us. Our focus was on two infant sons, the Raiders’ new Oakland home and the move of the Kansas City A’s to Oakland. By 1967 the flower children were competing for “shelf space” in the press with a host of other protest movements that had emerged or were developing: civil rights, gay/lesbian, feminism (I liked the no-bra look), Free Speech (Mario Savio), Black Panthers (Huey Newton), Marxism at Cal Berkeley (Angela Davis), Québec libre (Charles de Gaulle), and the Alcatraz encampment (Indians).

Q. The Monterey International Pop Festival occurred in June of 1967. Do you recall this event, or was it localized to Monterey? Do you recall any other mass gatherings of hippies? Did you ever experience the emerging culture of music festivals in San Francisco?

A. I don’t have any recollection of this event. Like many in my generation, I enjoyed the early introduction of rock, but as the noise grew louder, together with the rapid use of harder drugs, I turned off the sound. My observation was that the movement was co-opted by the slick and greedy shysters in the music industry and that, in reality, the flower children became victims of those who were in it only to make a very large and easy payday. The Stones and the Dead were more capitalist pigs than they were bleeding heart idealists.

Q. Did you notice an uptick in crime in San Francisco during the Summer of Love? Did the incoming drugs spark visible conflict in the streets, or were you far enough removed from those substances and that world?

A. As the movement advanced in numbers and notoriety and members of one protest group became commingled with others in parallel groups, overall chaos on the streets became more apparent. My instinct is that serious crime became more of an issue, but that is only a guess. I’ll use your words to answer your question: yes “I was far enough removed from those substances and that world,” while paying close attention to raising a family, rooting for the Raiders and A’s and lobbying Grammy for a dog. Hardly anything has changed in sixty years.

Q. Did the hippie presence in San Francisco die down after the Summer of Love? Was your subsequent experience in the Bay Area affected by the hippies?

A. After the Summer of Love we had the assassinations of MLK and RFK. The 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago was the Mother of all nightmares. The rise of the Symbionese Liberation Army, the Watts riot, anarchy in our major cities in subsequent years and even the divide that we as a nation experience today can in many ways trace their roots to the permissiveness that led to the hippie movement and its egocentric mind set. So yes, my experience in the Bay Area has been affected by the hippies.