“As the senior commander in Vietnam, I was aware of the potency of public opinion – and worried about it.” -GEN William Westmoreland [1]

Introduction

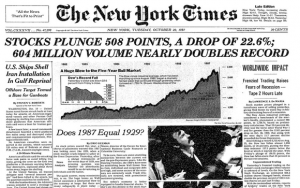

Courtesy of Politico

To this day, the Vietnam War remains a strong memory in the American psyche. The general consensus of the American public on Vietnam seems to be that it was an unwinnable war, fought for a questionable cause that ultimately led to nothing but dead Americans and a loss of faith in the U.S. government. For Melissa Woodbury, a Democrat with a political activist streak just coming out of college at the time, her own sentiment echoes the country’s memory: “I still feel very strongly about the war… It informed a lot of my thinking, it changed this country, not necessarily for the better… I would like to be able to trust the government and have faith in my elected officials… I would like to have fact be recognized as fact, but somehow we’ve lost all that.”[2] Yet, despite the almost universally negative outlook America shares on the Vietnam War today, public opinion at the time was far more conflicted, with most of the nation supporting both the war and its escalation in the early years while the rising popularity of TV news broadcasts continued to muddy the waters throughout the war’s duration.

Outbreak

The early years of the war are ones best categorized as years of indifference.[3] In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s when only a relatively small number of U.S. troops were deployed for the primary purpose of advising and instructing ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) units, the average American either didn’t know about the situation or simply didn’t really care. However, for more politically aware individuals such as Melissa Woodbury, the situation in Vietnam was often discussed. Having been recently married to Ronald Woodbury in 1965 after finishing school at Mount Holyoke College, Vietnam quickly became a common subject of discussion:

“I was in college from 62-65 and the big push hadn’t really started… so [my husband, Ronald] and I talked about it a lot. Interestingly my mother was all in favor of the war and [Ron] was all against the war and I was sort of in the middle [at the time] trying to explain my mother to [my husband] and [my husband] to my mother… I was just trying to make up my own mind and figure out what I thought…”[4]

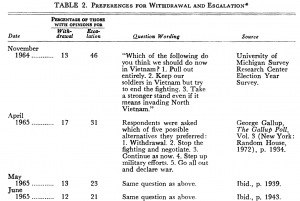

The localized interest from more politically active individuals in the country is reflected in early public opinion polls, as both withdrawal and escalation held higher percentages of support in 1964 than they did after the “big push” began during the following year (see image).[5]

The reason that support for both withdrawal and escalation decreased in 1965 was the massive deployment of troops that same year. By the end of 1964, U.S. ground forces numbered around 23,000, but by the end of 1965 that number had reached 184,000.[6] This drastic increase in troop deployments brought Vietnam to the forefront of public interest and drastically boosted public opinion as Americans “rallied around the flag” in support of the war effort. However, since most knew very little about the conflict, they could not provide any input on the withdrawal vs. escalation question, causing both percentages to drop.[7]

Escalation

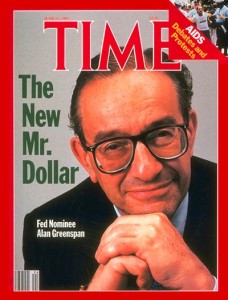

Courtesy of Talking Proud

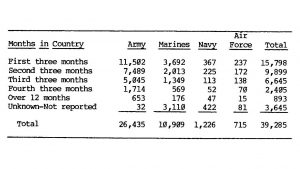

As the American escalation process continued through the late 1960’s public opinion slowly began to mature and take shape. By around 1967 public opinion reached a new mile marker, not only beginning to establish the general negative opinion Americans had of the war, but also a temporary one quite to the contrary. Although support permanently dipped below 50% in 1967, escalation sentiment reached its all-time high, peaking at around 55%.[8]

The beginning of the fall in public support for the war was in many ways due to increased media coverage. As the American troop commitment rose during the escalation period, so did the number of cameras and reporters. With the rising prevalence of the television in American homes and news broadcasts increasing in length to 90 minutes a night, scenes from the Vietnam War regularly reached Americans during dinnertime.[9] With the general public becoming more familiar with the horrors of warfare, support for a conflict that seemed so far away from home began to slide, yet most Americans, including Melissa Woodbury, were positive that

Dan Rather Reporting from Vietnam (Courtesy of Pinterest)

the war would be over soon. This also explains the peak in escalation sentiment and the significant drop in withdrawal sentiment (it’s lowest of the war at around 6-10%); although Americans did not support the war, they believed that it would not be long before victory was acheived, which meant that most either didn’t lean either way, or supported escalation to bring the war to a more rapid conclusion.[10] Melissa Woodbury echoes this view:

“It was awful. That was the first time that war came into our living rooms. Walter Cronkite reported every single night, we got the body count every night… Usually it was something like ‘we killed 7,000 of them and only 1,000 of us’… and then Westmoreland saying ‘just a few more, just a few more, just a few more’ and more troops went.[11]

The Tet Offensive

Courtesy of History.com

On January 30th, 1968, the Vietnamese new year, with the words “Crack the sky, shake the Earth”[12] the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong launched their largest offensive operation of the entire war. For the Americans and their allies, the offensive caught them completely off guard, as Tet was unofficially recognized as a day of ceasefire and American military analysts believed that the NVA and VC had nowhere near the manpower to conduct an offensive on the scale of Tet. Although Communist forces initially made fairly significant gains, they were soon thrown back and by the end of the offensive their forces had been completely crushed by American firepower, with the communist casualties estimated to be around 10,000 in the first few days compared to 249 American deaths.[13]

Yet from a public opinion standpoint, the Tet Offensive was a complete disaster for the United States. For some time, both the American government and military establishment believed that the communist forces in Vietnam were on the brink of defeat. NVA and VC activity had been on a steady decline since mid-1967 and American military analysts believed that it meant that the communists were rapidly running out of men and material. When Tet struck, this belief was completely crushed. Although she was living in Argentina when the offensive started, for Melissa Woodbury, and many other Americans, Tet turned what was viewed as a soon-to-be winnable mistake into an unwinnable one:

“…we kept getting the reports on how much progress we were making and then the Tet Offensive happened and everything suddenly became clear that we were not making any progress… [I felt they weren’t telling the full story] and whether that’s fair or not I don’t know, but certainly we had so much mistrust in what the military and the President were saying that it was hard to believe their figures. It was all this rosy talk about “we’re winning, we’re winning, we’re winning” and obviously we were not winning and we did not win.” [14]

Although the start of the Tet Offensive itself began to cause public opinion to waver, the final nail in the coffin came on the evening of February 27th, 1968. Having recently returned home from on-site reporting in Vietnam, Walter Cronkite closed out the nightly CBS news report with the following words:

(Courtesy of YouTube)

“Walter Cronkite was probably the most trusted man in the country”, said Melissa Woodbury, “When he became convinced that the war was unwinnable and said it, that had a huge impact on his viewers…[15] lots of people rethought”[16]

By November 1968, public support for withdrawal rose from 10% to 19% and public support for escalation dropped from 55% to 34%.[17] By October 1968, 63% of the population believed that

Vietnam was as mistake.[18] Even more drastic was the fall in support for the Johnson administration, which hit a record low of 26% by the end of the Tet Offensive.[19]

Despite the government and military stating that Tet was a landslide of a military victory, their voices were drowned out by the images on the television and the words of Cronkite. Military analysts soon discovered that Tet was part of an extremely predictable yearly pattern of communist activity, and subsequent offensives in the following years continued to grow weaker, but it was too late. “[Tet] contributed to the breakdown in trust of the government… we certainly did not trust what they said.”[20] said Melissa Woodbury, showing how Cronkite’s broadcast had effectively completely discredited the military and the White House as reliable sources of information on the conflict. “[For] the fist time in American history a war had been declared over by an anchorman.”[21]

Downward Spiral

Although U.S. intervention would continue until 1973, the domestic effects of the Tet Offensive sealed the fate of the American mission in Vietnam. There were other public opinion disasters during Vietnam, but they simply served to increase the speed at which civilian support spiraled downward. Probably the most notable was the draft, which was re-instituted on December 1st, 1969.

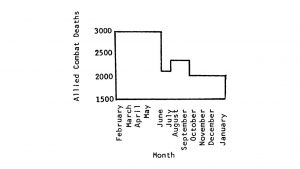

The draft brought men into the ranks of the military who had no wish to fight and the single, one-

year deployment rule that was instated for draftees to try and improve public opinion did little more than to force the expansion of the draft and increase casualties, as the ranks of the military were flooded with inexperienced, green troops (40% of American deaths were men who were on their first three months in country compared to the 6% who were on their last three).[22] As anti-war sentiment grew and the draft brought in the war’s protesters, incidents of “fragging” (intentionally killing one’s superior officer or NCO) increased drastically.[23] Fortunately, for Melissa Woodbury, her husband was never considered for the draft due to marital and parental status, but a friend of theirs was:

“…one of our friends got a really good number and didn’t have to go and he celebrated, he got drunk, he was so happy that he didn’t have to go.”[24]

Courtesy of The Northwest Veterans Newsletter

Another event that further negatively impacted public opinion were the invasions of Laos and Cambodia. Despite being part of Nixon’s “Vietnamization” program, which was meant to slowly withdrawal American ground forces in the region while building up the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), domestically they served little more than to trigger more protests (the invasion of Laos in particular was conducted primarily by ARVN units; however, they performed miserably).[25] The invasion of Laos provided Melissa Woodbury with a strong personal memory:

“…when Nixon went into Laos in 1971 one of [Ron’s] fraternity brothers killed himself over it. He’d been working so hard in the anti-war movement that when Nixon upped it again and went into Laos he committed suicide he was so distraught.”[26]

This small story, while no means the norm, reflects strongly how Americans at home felt about the war. In 1973, American forces officially pulled out of Vietnam and on April 30th, 1975 Saigon fell to Communist forces. Although it made the news, not many cared; the American people had had enough.

Conclusion

Courtesy of Encyclopedia Britannica

Vietnam marks the first time in American history that a war was decided not on the battlefield, but in the minds of the American people. According to military analyst Thomas C. Thayer: “The Americans couldn’t win in Vietnam but they couldn’t lose either as long as they stayed.”[27] Had U.S. forces had more time to effectively implement Nixon’s “Vietnamization” strategy, it is possible that South Vietnam would have been able to hold its own once the American military left, but the nightly news broadcasts depicting scenes of violence like none that most Americans had ever seen before and the public statements of prominent figures such as Walter Cronkite served to shorten the fuse of the public opinion time bomb and ultimately bring the war to its unsatisfactory conclusion. Although Vietnam was fairly casualty-light in comparison to other major wars fought by the United States, especially considering Vietnam’s length, direct TV exposure to the war made those casualties more human and less of a statistic, a fact that was exploited heavily by the North Vietnamese:

“…For each additional day’s stay, the United States must sustain more casualties. For each additional day’s stay they must spend more money and lose more equipment. Each additional day’s stay, the American people will adopt a stronger anti-war attitude while there is no hope to consolidate the puppet [South Vietnamese] administration and army.” [28]

Aside from simply costing the U.S. the war, public outrage caused a massive decline in both trust and support for the Federal Government, the effects of which are still being felt to this day. “I would like to be able to trust the government and have faith in my elected officials”, stated Melissa Woodbury at the end of her interview, “…I would like to have fact be recognized as fact, but somehow we’ve lost all that.”[29]

Timeline

Bibliography

[1] “WESTMORLAND”, The Washington Post, (WP Company: 09 Feb. 1986): https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1986/02/09/westmorland/878f7d1c-7619-4a2e-8806-298e5fb7fc6d/?utm_term=.2a72bdd26b12

[2] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[3] Lunch, William L. , and Peter W. Sperlich. “American Public Opinion and the War in Vietnam.” The Western Political Quarterly 32, no. 1 (1979): p. 29 [JSTOR]

[4] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[5] Lunch: p. 27

[6] Thomas C. Thayer, War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam, (Westview Press, 1985): p. 34.

[7] Lunch: p. 29

[8] Lunch: p. 26-27

[9] H. W. Brands, American Dreams, (New York: Pearson Education, 2010): p. 287.

[10] Lunch: p. 27

[11] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[12] Kevin Robbie, “Crack the Sky, Shake the Earth…” A Look Back at Tet, (University of Illinois: Feb. 14, 2015): http://www.thursdayreview.com/TetOffensiveVietnam.html

[13] Robert W. Merry, Cronkite’s Vietnam Blunder, (The National Interest: July 12, 2012): http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/cronkites-vietnam-blunder-7185

[14] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[15] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[16] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Email, April 8th, 2017.

[17] Lunch: p. 27

[18] Lunch: p. 25

[19] Brands: p. 157

[20] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[21] David Halberstam, The Powers that Be, (New York: Knopf, 1975): p. 514

[22] Thayer: p. 114

[23] Mark Depu, Vietnam War: The Individual Rotation Policy (History Net). http://www.historynet.com/vietnam-war-the-individual-rotation-policy.htm

[24] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[25] Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History, (New York: Penguin Books, 1997): p. 644-645

[26] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

[27] Thayer: p. 257

[28] “Enemy Emphasis on Causing U.S. Casualties: A follow-up”, (Analysis Report, May, 1969), 16-17.

[29] Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

Transcript Selection

-Interview with Melissa Woodbury, conducted via Skype, March 25, 2017.

Q: In March of 1965, Johnson deployed 3,500 Marines to South Vietnam. Within a few years this number was over half a million. What did you think about the escalation of the war and how did it affect your views on the war?

A: It was awful. That was the first time that war came into our living rooms. Walter Cronkite reported every single night, we got the body count every night… and then Westmorland saying “just a few more, just a few more, just a few more” and more troops went. Compounding the whole thing was the draft. Grandpa was ok because we got married and then when married men could go I was already pregnant with your mother and they weren’t taking fathers. We didn’t do it on purpose to avoid the draft, but it worked out well. I had friends who were ready to go to Canada… it was a lottery so one of our friends got a really good number and didn’t have to go and he celebrated, he got drunk, he was so happy that he didn’t have to go. Without a volunteer army the people that were going didn’t want to go and…. It was hard, especially when the reports every single night were the body count. When Johnson announced that he wasn’t going to run again because of the war, Grandpa jumped up, he ran out of the room, he climbed up the stairs to where the Garrison’s were living and they were yelling and screaming… In September of 1968 we went to Argentina for 6 months so we weren’t doing as much about it by then, but when Nixon went into Laos in 1971 one of Grandpa’s fraternity brothers killed himself over it. He’d been working so hard in the anti-war movement that when Nixon upped it again and went into Laos he committed suicide he was so distraught. I still have strong feeling obviously, about the war. It was tough for people my age who thought the way I did.

Q: Did you think the media projected a clear position on the war during the time period?

A: No, it was much more focused on just reporting the news. There was ABC, NBC and CBS (CNN didn’t exist even, certainly not FOX). It was Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley and the ABC guy, I forget his name, but it was very much just the facts. Who knows, maybe they were doing all sorts of things that we didn’t know about, but there was no assumption of shading the story one way or the other. Walter Cronkite was probably the most trusted man in the country (that is the CBS news anchor). When he became convinced that the war was unwinnable and said it, that had a huge impact on his viewers, but it wasn’t a constant slant the way [many news networks] are today.