The Nuclear Freeze Movement: A Personal Recollection

By J. Miles Krein

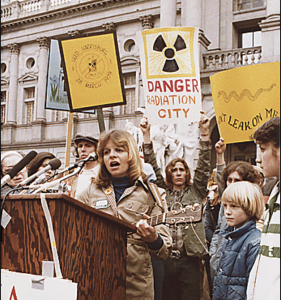

Reagan’s apparent indifference to the prospect of nuclear war roused the attention of many Americans, including Scott Krein. Instead of waiting for world events to unfold on their own, Scott decided to make his concern known. On the 12th of June in 1982, Scott participated in a protest as part of the larger Nuclear Freeze movement that demanded that the United States cease the production of nuclear weapons. At the time, this protest was determined to be the largest peaceful gathering to occur within the US. “It was truly something else,” Scott said of the protest. “I was energized and motivated by all the people around me… I felt like we were fighting for something positive.”[1] However, despite the monumental nature of the June 12th protest, H. W. Brands fails to mention this event in his book American Dreams. While Brands writes about goals and context of the Nuclear Freeze movement when discussing the Reagan presidency, the author neglects the experiences of the average American citizens that made the movement possible. Due to this oversight, American Dreams fails to capture the true significance and impact of the Nuclear Freeze movement. In addition, Scott’s interview and other primary sources challenge certain assertions made by Brands regarding the Nuclear Freeze movement.

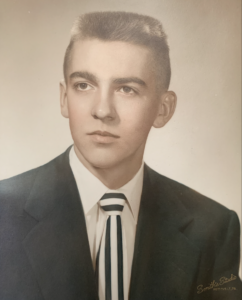

James Scott Krein was born on September 9th, 1961 in San Diego, California and is the son of a Korean War veteran. As a child, Scott’s family moved relatively often and lived in places such as Guam and Japan due to his father’s active membership in the military. Scott recalls that his father’s military service influenced his political and social awareness later in life: “I remember being aware of what the military was doing because I was around that sort of environment so often… I remember the Vietnam War and learning about Hiroshima and Nagasaki and nuclear weapons when I was in school.”[2] While Scott was too young to take part in the Vietnam War protests, he remembers witnessing the protests on the news and hearing about the anti-war movement from his parents. According to Scott, he was able to understand that “a lot of people would die” if the United States did not withdraw from Vietnam. “That’s why people were upset,” Scott said of his recollection of the Vietnam War.[3]

Regarding his experience at the Nuclear Freeze protest that took place on June 12th of 1982, Scott said: “We got there the night before and spent the night on the street in front of the United Nations building. No tent or sleeping bag or anything… I slept on the sidewalk with just my sweatshirt and jeans.”[4] Apparently, Scott failed to consider that an overnight event might warrant the purchase of a tent or a sleeping bag. While Scott had originally agreed to go to the protest for the musical performances, he admits that the speakers and political figures are associated with stronger memories. Additionally, Scott mentioned that “one of my most vivid memories of my life is when we started marching and turned a corner near the United Nations building and we were faced by a row of New York cops with machine guns. I wasn’t scared, but I remember that it agitated me. Yeah there were a lot of people there, but no one was being violent.”[5] Scott’s interview regarding the June 12th Nuclear Freeze protest provides a personal and sincere recollection of one of the largest public demonstrations in American history.

While Brands’ American Dreams details the context and the goals of the Nuclear Freeze movement, the author fails to include any mention of the massive protest that took place on June 12th of 1982. Furthermore, Brands’ book includes no mention of a personalized experience akin Scott Krein’s recollection. Despite the flaws in Brands’ characterization of the Nuclear Freeze movement, the author effectively delineates why many Americans became concerned about the use of nuclear weapons under Reagan; “Reagan’s arms buildup and bellicose rhetoric… had set many Americans on edge.”[6] Brands’ assertion that Reagan’s demeanor was a major catalyst for the Nuclear Freeze movement appears to match Scott’s recollection; “With the people that we had in office at the time [of Reagan’s presidency], it was entirely believable that they could start an atomic war and destroy the world.”[7] During Reagan’s presidency, Scott decided to join the Nuclear Freeze movement and take part in the June 12th protest because he feared the possibility of a nuclear war. Scott asserts that he did not fear such an outcome during Carter’s presidency, though he admits that he was not especially politically active until Reagan took office.

While Brands correctly describes the major catalyst for the formation of the Nuclear Freeze movement, he fails to give a full description of how the movement spread. In American Dreams, Brands credit various pieces of mass media for spreading the notion that the use of nuclear weapons would lead to a cataclysmic scenario. Brands mentions that the television program The Day After left “tens of millions of viewers…wondering how long the human species had left.”[8] In contrast, Scott recalls that he was made aware of the impending nuclear threat by a college professor: “I took a college course on American foreign relations… I don’t think the professor would have discussed [the use of nuclear weapons] as much as he did if it were not for the political circumstances at the time.”[9] Furthermore, Scott recalls that he heard about the June 12th Nuclear Freeze protest from a fellow student at Oberlin College. Scott never mentioned the influence of the media regarding his decision to become involved with the Nuclear Freeze movement. Newspaper articles written at the height of the Nuclear Freeze movement also tend not to credit the media for the movement’s spread. Instead, sources such as the New York Times characterized the Nuclear Freeze movement as a “grass-roots crusade.”[10] Though pieces of mass media may have informed some people about the movement, neither relevant newspaper articles nor Scott’s recollection concur with Brands’ assertion.

American Dreams also fails to address the role of religion in the Nuclear Freeze movement. Brands addresses the role of religion during Reagan’s presidency, but only in the context of providing the 40th President of the United States with a new constituency that supported his policy of reinvigorating America’s nuclear arsenal. However, according to the New York Times, the Nuclear Freeze movement was endorsed by “American churches – particularly the Roman Catholic church.” [11] Scott’s experience at the June 12th protest confirms the New York Times’ assertion: “There were a lot of different religious groups there. I remember Quaker and Catholic groups in particular. When I first got there, I talked with two guys who I later found out were part of a Catholic organization.” [12] Brands characterizes religious groups as primarily supporting the Republican political agenda during Reagan’s presidency. However, both Scott’s interview and the New York Times indicate that religious groups did not strictly adhere to Reagan’s platform throughout his presidency. As Reagan’s rhetoric created greater fears of an impending nuclear war, more American citizens began to endorse the Nuclear Freeze movement. Religious organizations also experienced this anxiety, forcing institutions such as the Catholic church to reconsider which side of the political aisle held the moral high ground. Brands’ description of the Nuclear Freeze movement includes no account of the role played by religious groups, a phenomenon that is highlighted in Scott’s interview and other primary sources.

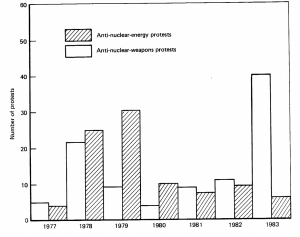

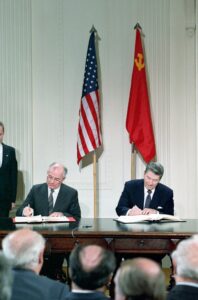

Furthermore, Brands appears to indicate that the Nuclear Freeze movement was a failure. In the closing paragraph of the section written about the Nuclear Freeze movement, the author says that Reagan “rebuffed the nuclear freezers.”[13] However, Scott sees the Nuclear Freeze movement as a success: “I saw it as a success. [The INF treaty] that was passed later was part of that success.”[14] Brands makes no mention of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty that was passed in 1987 when discussing the Nuclear Freeze movement. While the treaty occurred five years after the Nuclear Freeze protest of 1982, Scott perceives the two events as directly related to one another. Without the massive rally that took place on June 12th of 1982, the INF treaty would not have been realized. Furthermore, political scientist Marvin Overby also argues that the Nuclear Freeze movement was a success. According to Overby, “by 1983, opponents of the freeze were themselves offering a version of the freeze.”[15] Overby asserts that after 1983, Congress was generally supportive of the Nuclear Freeze movement. Specifically, by 1983, former opponents of the Nuclear Freeze were endorsing legislation that advocated for a mild form of nuclear disarmament. Brands’ conception of the Nuclear Freeze movement as a failure contradicts Scott’s interview and social scientific analyses of the movement.

“President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Mikhail Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty in the East Room” via Wikipedia

In his book American Dreams, H. W. Brands adequately describes the context and goals of the Nuclear Freeze movement. However, Brands fails to consider the unique experiences of the average American citizen that made the movement possible. Due to this oversight, Brands is unable to effectively articulate the significance and impact of the Nuclear Freeze movement. Scott Krein’s interview sheds light on the aspects of Brands’ account that lack information, in addition to challenging certain elements of Brands’ description. Specifically, Scott’s interview challenges Brands’ assertion that the popular media spread information about the Nuclear Freeze movement and the author’s notion that religious groups continuously supported Reagan’s platform throughout his presidency. Furthermore, along with social scientific accounts, Scott’s interview demonstrates that the Nuclear Freeze movement achieved some degree of success. Scott’s decision take part in the June 12th Nuclear Freeze protest allows one to create an accurate picture of the movement: the opposition to Reagan’s nuclear policy was a grassroots movement that attracted the attention of religious groups and was made possible through the dedication of average the American citizen.

Citations

[1] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, May 4th, 2022.

[2] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, April 25th, 2022.

[3] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, May 4th, 2022.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] H. W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2011), 257.

[7] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, April 25th, 2022.

[8] H. W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2011), 258.

[9] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, May 4th, 2022.

[10] Robert Shogan, “Nuclear Freeze Movement Emerges As Political Test,” Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, CA), Apr. 17, 1982.

[11] Fox Butterfield, “Anatomy of the Nuclear Protest,” New York Times (New York, NY), Jul. 11, 1982.

[12] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, May 4th, 2022.

[13] H. W. Brands, American Dreams: The United States Since 1945 (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2011), 259.

[14] Zoom interview with Scott Krein, April 25th, 2022.

[15] Marvin Overby, “Assessing Constituency Influence: Congressional Voting on the Nuclear Freeze, 1982-83,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 16, no. 2 (1991): 308.

Image Credits (in order of appearance)

“WNYC Covers the Great Anti-Nuclear March and Rally at Central Park, June 12, 1982,” WNYC, last modified June 12, 2015, https://www.wnyc.org/story/wnyc-covers-great-anti-nuclear-march-and-rally-central-park-june-12-1982/.

“The Nuclear Freeze Movement,” Outrider, last modified February 21, 2018, https://outrider.org/nuclear-weapons/articles/nuclear-freeze-movement.

“President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Mikhail Gorbachev signing the INF Treaty in the East Room,” Wikipedia, last modified October 15, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Ronald_Reagan_and_Soviet_General_Mikhail_Gorbachev_signing_the_INF_Treaty_in_the_East_Room.jpg.

Transcript (selected section from an interview done over Zoom with Scott Krein on April 25th, 2022)

Miles: “Did you ever take part in any protests as part of the nuclear freeze movement?”

Scott: “Yes I did. I attended arguably the largest public protest in the United States in June of 1982 in New York. That was the largest one I went to. I drove up there and spent the night across from the United Nations building. I think nearly one million people showed up. I know it didn’t make the biggest difference at the time, but I knew it was important for politicians to see bodies out on the street. We showed how many people were concerned for the rest of the world. And I guess it was successful. [The INF treaty] that was passed later was part of that success, at least I saw it as a success.”

…

Miles: “What made you decide to become involved in the nuclear freeze movement?”

Scott: “I was concerned about the amount of human suffering that a nuclear war might cause. I knew a lot of people would die and I didn’t want to see that happen. It would be a horrific thing to happen. And then when I got older and began to really think about the lessons we learned from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I realized that it’s not just about nuclear proliferation or disarmament. It’s about social justice and particularly the environment. It’s all connected… And you saw people like Reagan, and Henry Kissinger before him, overthrowing governments in Latin and South America. They even openly defied Congress to do it. Reagan was frightening. At the time, both the US and the Soviet Union had so many nuclear weapons that they could have exterminated humanity multiple times over. With the people that we had in office at the time, it was entirely believable that they could start an atomic war and destroy the world.”

…

Miles: “Did you ever see a connection between the United States’ possession of nuclear weapons and elements of our political policies?”

Scott: “Yes absolutely. Our nuclear arsenal was supposed to be our great strength, and that is the way it is today. Apparently we had the greatest military in the world and its strength was unparalleled, according to our government. Because of that, [other countries] have to do what we say. There’s always this implicit threat that we could destroy them if they don’t. It’s all related. We can bully other countries into doing what we want. It’s just a way of extending imperialism. The presence we had in other countries during Reagan’s time in office was an extension of the influence of our nuclear arsenal. Those countries had to let us have our way or we might destroy them. Nicaragua and Argentina, it was all the same… A big problem is that we can’t use [our nuclear weapons]. If someone uses a nuclear weapon, then the other country will retaliate. Then we will retaliate, then the world will end. I think they have a big effect on our foreign policy, our domestic policy, and on our individual psyche. The threat of a nuclear war and a nuclear winter made me feel more human than American.”

Sources for Further Research

Hogan, M., and T. Smith. “Polling on the Issues: Public Opinion and the Nuclear Freeze Movement.” The Public Opinion Quarterly 55, no. 4 (1991): 534-569.

Wittner, S. “The Nuclear Freeze and Its Impact.” Arms Control Today 55, no. 10 (2010): 53-56.

Overby, L. “Assessing Constituency Influence: Congressional Voting on the Nuclear Freeze, 1982-83.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 16, no. 2 (1991): 297-312.

Marullo, S. “Leadership and Membership in the Nuclear Freeze Movement: A Specification of

Resource Mobilization Theory.” The Sociological Quarterly 29, no. 3 (1988): 407-427.