Beginning primary source research can be tough. But it is also rewarding, and I found that each time I went into the archives I was appreciative to be able to do historical research. I found some interesting things and I still have a lot more work to do.

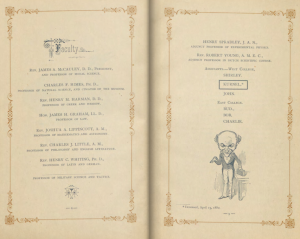

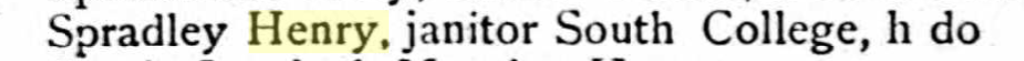

Laurent LaVallee was a professor at Dickinson College, accused communist, and employee of the United States government as both a soldier and economist. When I decided upon LaVallee as my topic, he seemed like a shadowy figure shrouded in the smoky circumstances of the Red Scare and the twists and turns of academia’s politics. As I have begun the process of researching his Life, Times, and Memory, my goal was to clear a bit of the smoke and create a map for the twists and turns. In order to do this, I took a few trips to the Dickinson Archives and used online databases.

To The Archives!

My first step, before I went into the physical archives, was to look at the Dickinson Archives online collection, where I fou

-nd some articles in the Dickinsonian from the year that LaVallee was fired, and perhaps more importantly, the finding aid for LaValles’ file. With this I was able to plan trips to the archives and study similar material at the same time. This helped to keep my research (and notes) more organized, though I quickly learned the importance of this when a third trip to the Archives was necessary at the last minute, in order to cite my sources.

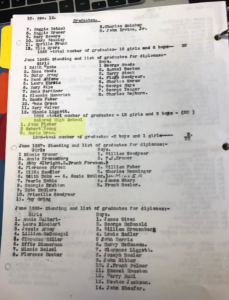

The articles in the Dickinsonian (as student written sources) focused heavily on student reaction to the proceedings of the case. So, for my first trip, I was interested in looking further at the students’ reactions. One of the articles from the Dickinsonian referenced a petition by students that protested the firing of LaVallee. I found the petition. In fact, I found at least 15 copies of this petition. At first, I could not understand why there were so many copies, but I realized that it was because each copy had different signatures, a testament to the at least dozens of students that disagreed with LaVallee’s suspension.

One of my other favorite finds was also a source in duplicates. I came across a several copies of the report by administration announcing the removal of LaVallee from the College. Upon closer look, I realized that the writings were edits made by William Edel (president of the College at the time) because he signed them at the end (thanks, Edel!). Sure enough, when I compared them to the final copy, the handwritten changes had been made.

I’m glad that I found these sources, for what they helped me to learn about the LaVallee situation, but also because I think it reminded me the of the value of archival research. Though it can be tough to handle documents by hand, without the benefit of technology that identifies keywords, comparing the signed petitions and the copies of Edel’s report in-person gave me insight into the sheer number of students that supported LaVallee and into Edel’s thought process.

Online Research Between In-Person Visits

After this, I did another round of at-home, digital, research where I looked at secondary sources (see second journal entry), into the AAUP (American Association of University Professors, who censured the college after LaVallee’s firing), and Ancestry Library. I knew going into this project that the biggest challenge would be looking at LaVallee’s life after Dickinson, because in talking to both Malinda Triller-Doran and Professor Pinsker, I was warned that there was not much research done on the topic previously.

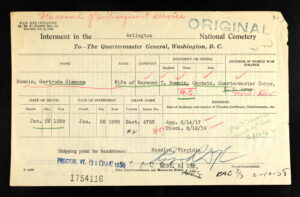

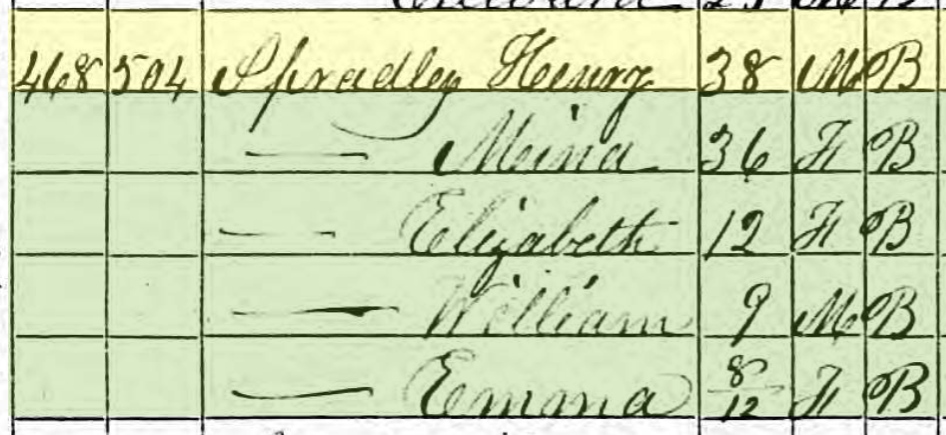

I started out on ancestry with a basic search of his name and birthplace, Worchester, MA and immediately found a birth record and death record (from Plainsfield, VT in 1998). With a little bit more digging, I found records of his entry/discharge into the army in 1944/1945 and his marriage to Louis Merrix in 1948. I was able to find these documents once I realized that on his birth record his name was listed as Lawrence, not Laurent, LaValle (though with the same birth date and place as was listed in other sourcs).

Massachusetts Birth Record, 1913, Laurent R. LaValleeves, Melinda helped me to use Newspapers.com to find a report of his hiring at Goddard College in 1961, after he was fired from Dickinson.

Additionally, I saw some sources that referred to him as Raymond, his middle name. These were mostly repeated documents, but having a potential pseudonym was helpful. I confirmed Raymond as an alternate name when a source in the Dickinson Archives had him listed as Raymond (a colleague referred to him as Raymond in a letter of recommendation to the College). This will be helpful for further research, and perhaps explains why he seemed to disappear after he left Dickinson.

Back to the Archives!

This brings me to my next trip to the archives, where I wanted to establish a timeline of his accusal, trial, suspension, and removal at Dickinson. I was also on the lookout for a source that referred to Herbert Fuchus, the person who originally named LaValle as a communist in his trial with the Committee on Un-American Activities. One of the first things I looked at was the correspondences between William Edel, other administrators, faculty, and lawyers (mostly David Kohn, who seemed to be Edel’s personal lawyer, though I’m not yet sure why Kohn is not listed as the College’s lawyer, instead). These letters mostly went over possible evidence for the trial against LaVallee and had a distinctly accusatory tone. This was consistent with McCarthy era (and according to Malinda, with Edel’s reported personality).

I also was able to locate the court record of the trial Herbert Fuchus, where he named LaVallee as a communist (a common practice for these trials). The timing of these sources allowed me to construct a timeline from start (when LaVallee was accused) to finish (when he was fired) for the affair, overall about a year.

What’s Next?

Going forward, I would like to do some more research into the timeline of events and dedicate a few days into fully reading the hundreds of pages of LaVallee’s trial documents, including a transcription and exhibits, which I skimmed, but did not have the time to read in detail. Additionally, I will investigate the AAUP documents that I discovered in my last trip to the archives in speaking to Malinda, including Dickinson’s report of the AAUP censure. I also have plans to contact the other colleges where LaVallee worked and request through Inter Library Loan a copy of his obituary that Malinda helped me to locate with the Dickinson Archives account through Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

“Board Holds Hearing For Dr. LaVallee.” Dickinsonian, April 27 1956.

“Dr. L. LaVallee Hearing held Friday, April 26.” Dickinsonian, April 13 1956.

“Economics Teacher Named at Goddard.” The Burlington Free Press (Burlingtonette, VT), Jul. 14, 1961.

Students of Dickinson college, “Statement of Student Belief” 1956, Carlisle, PA, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Edel, William E., Carlisle, to David Kohn, April 16 1956, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Edel, William E., Carlisle, to David Kohn, May 31 1956, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Edel, William E., “RE: Professor Laurent R. LaVallee.” June 1, 1956, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Hearing Before the Committee of House, Un-American Activities, House of Representatives, Eighty-Fourth Congress, First Session, Investigation of Communist Infiltration of Government, December 13, 1955, pg. 2999-3000.Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Kohn, David, Harrisburg, to William E. Edel, March 30 1956, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

“LaVallee questioned by the House Un-American Activities Committee.” Dickinsonian, March 9 1956.

“LaVallee Action Protestsed by Students and Faculty.” Dickinsonian, March 23 1956.

“Massachusetts, U.S., Birth Index, 1860-1970.” AncestryLibrary.com. 2023

“N.S.A. Sends a Statement on Recent Issue.” Dickinsonian, May 4 1956.

“Oregon, U.S., Country Marriage Index, 1851-1975.” AncestryLIbrary.com. 2023.

“U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014.” AncestryLibrary.com. 2023.

“Vermont, U.S., Death Index, 1981-2002.” AncestryLibrary.com. 2023.