After researching the Student Rebellion of 1870 through primary source documents from Dickinson College and modern secondary source publications, it came time to hear the voice of Carlisle and Pennsylvania as a whole; newspapers. I began with online databases, specifically The Library of Congress’s Chronicling America. Once there, I was able to search for articles by limiting the entries to only those from Pennsylvania in 1870, and even further using keywords and phrases such as “Dickinson College”, “Dickinson”, “Carlisle” and “Rebellion”. It is important to note that I entered the individual terms into the “ANY of these” bar, as I was hoping to broaden my search sufficiently enough to get useful hits.

Although the two main Carlisle newspapers from the period seem to not be available in the Library of Congress’s database, the student rebellion turned out to be noteworthy enough to make it into many other publications throughout Pennsylvania. The first was an article from The Bloomfield Times, a local paper from New Bloomfield, PA. Aside from the date of the absentees return to Dickinson, it provided no new information; however, the fact that a local paper from a small town 20 miles north of Carlisle was covering the rebellion meant I was likely to find articles in larger, more significant publications.

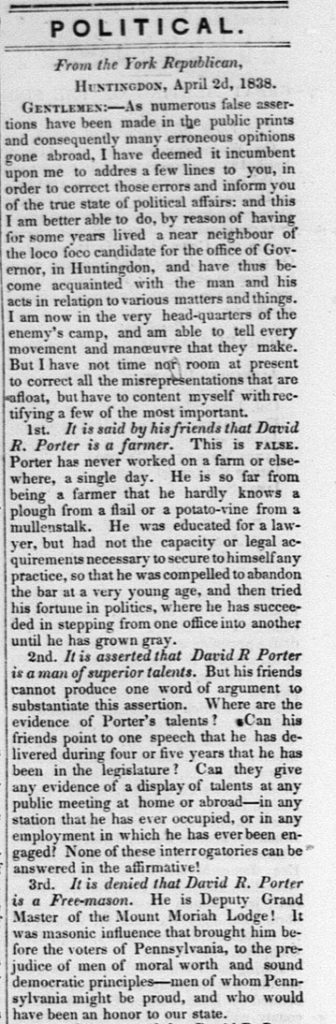

Evening Telegraph Article (indicated by sections highlighted in red), Courtesy of Chronicling America

My hypothesis soon proved correct with the discovery of a rather long, front page article in Philadelphia’s Evening Telegraph published on May 5th, 1870. Surprisingly, this article proved to be one of the most detailed summaries of the rebellion I had come across thus far, although it only covered up to the suspension of the sophomore and junior classes. The article includes details on the debate between student and faculty over the penalty students received, which was based on the school’s own policies (the students wanted to take 8 minus marks, the combined penalty for a misdemeanor and missing class, instead of the upwards of 500 placed upon them). The article also provided a transcription of the notice students were sent by the President’s office regarding the rebellion:

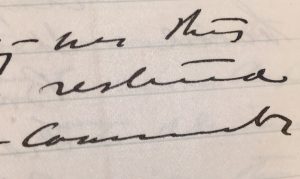

“Resolved, That the President announce to the members of the Sophomore and Junior Classes that any members of those classes who shall absent himself from recitations on Monday, May 2 without sufficient excuse, presented during the same day to the President, shall be and is hereby suspended from college until the first Thursday of September next, to be restored at the end of that time only on making satisfactory acknowledgment to the faculty, and that any student so suspended is required to leave town for home on Tuesday, May 3, before 5:20 P.M., under penalty of expulsion.”

A Microfilm Viewer at Cumberland County Historical Society. The film is fed through the spool at the bottom and viewed through a magnifier on screen.

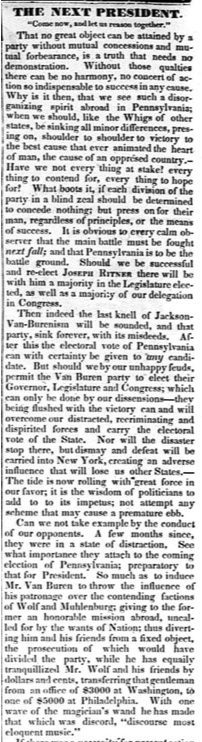

Having been fairly successful in my search for articles about the rebellion, I decided to try and tackle one of my other research questions: the reception in the 15th Amendment in Carlisle. Unfortunately, I got very few hits on Chronicling America and this is also when I discovered that the database didn’t have any of the Carlisle newspapers from the time. Luckily, however, the Cumberland County Historical Society, which is located just a block or two off campus, has a copy of every issue of The American Volunteer and The Carlisle Herald (the town’s two major publications during the period) on microfilm; a method of viewing documents that allows years worth of papers to be stored on a single role of film.

I began by taking a look at the Volunteer and was almost immediately successful. On the second page of the April 14th edition, a weekly column titled “Our Washington Letter” toted some rather strong opinions on the passage of the 15th Amendment. I immediately knew I had found exactly what I was looking for when the second sentence of the article read: “Sambo (a racial slur for African Americans) is no longer merely ‘a man and a brother,’ but is now a full pledged fellow citizen of African ‘scent”.[1] The article eventually came to the conclusion that the African American race did not deserve the right to vote because “nineteen twentieths [of them] could neither read nor write…”, meaning that the 15th Amendment was pushed through by Radical Republicans in Congress who simply wanted to use the African American vote to stay in power (an article from another paper stated that the Radicals were “enslaving the negroes” to their cause)[2] I found further articles in other issues of the Volunteer that claimed the amendment had been passed “not in the mode prescribed by the Constitution itself, but by the arms of the military consulate, acting in the name of the President and Congress”.[3] There were also several articles about a Senator Revels, who was an African American, that contained such blatant and over the top slander as to put the 2016 election to shame; the articles referred to him as “a full blooded, curly haired, ebony shinned, big-footed negro” and stated that “The attempt, therefore, to make it appear that this negro [Revels] is a man of talent – ‘a statesman and scholar’ – is a fraud”.[4]

Ultimately, I was somewhat amazed as to what just a few hours of newspaper research was able to tell me about not just the student rebellion, but also Carlislian sentiment regarding the 15th Amendment. Admittedly, I have yet to examine any articles from the Herald, and the existence of the amendment’s celebratory parade leaves plenty of room for a mixed response; yet, so far everything I have come across has been both highly revealing and condemning. I greatly look forward to continuing my examination of the local papers in regards to the 15th Amendment.

[1] “Our Washington Letter,” (Carlisle) American Volunteer, April 14, 1870, p. 2: 5, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

[2] “Our Washington Letter,” (Carlisle) American Volunteer, April 14, 1870, p. 2: 5, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

[3] “The Fifteenth Amendment,” (Carlisle) American Volunteer, February 3, 1870, p. 2: 2, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

[4] “Negro U.S. Senator,” (Carlisle) American Volunteer, February 3, 1870, p. 2: 2, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA; “Senator Revels,” (Carlisle) American Volunteer, April 21, 1870, p. 2: 2, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.