Stages of American Electoral Democracy

- Candidate announcements

- Nomination campaigns

- Party Nominations

- General Campaigns

- General Elections

- Counting and Certifying

- Inaugurations / oath-swearings

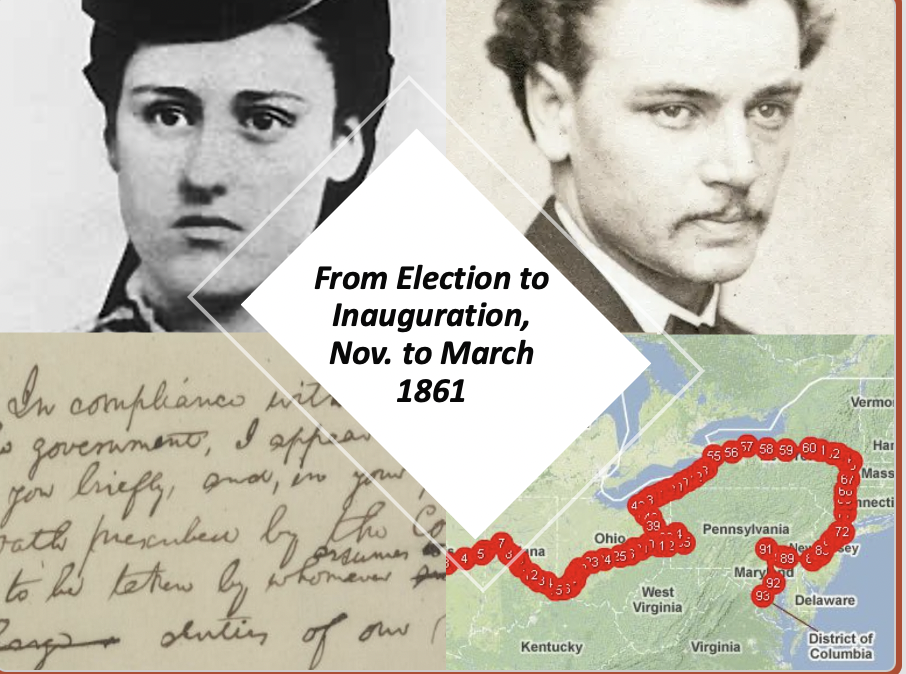

Crisis of 1861

Lincoln’s Secession Crisis, And Ours

Compromise was the most lethal epithet in the reformer’s lexicon. It is their refusal to compromise that makes reformers so attractive and frustrating. –Oakes, p. 135

For nearly two years after the Civil War began there was nothing Abraham Lincoln could do to satisfy Frederick Douglass. –Oakes, p. 169

Douglass actually endorsed all paths to emancipation. He was a flexible dogmatist. The goal mattered much more than the means of achieving it. –Oakes, p. 170

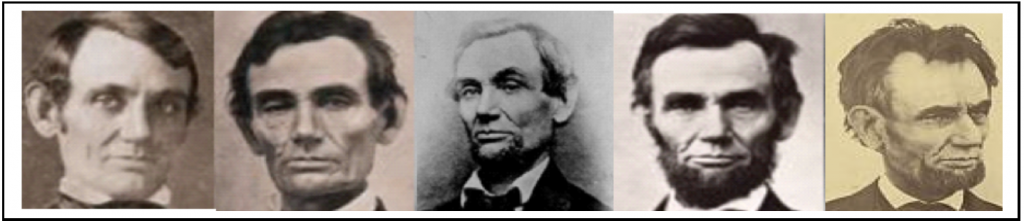

Image Gateway

These images represent a selection of Lincoln photographs from his earliest (1846 or 1847) to the final known portrait (March 1865). Do you think Lincoln was trying to convey any specific political message with his public image?

Brief Political Chronology of the Civil War (1861-63)

November 1860 – March 1861 // Lincoln assembles cabinet of party leaders

March – April 1861 // Lincoln overrides advisors on Fort Sumter crisis

April – May 1861 // Lincoln defies Chief Justice on civil liberties

July 1861 // Lincoln pressures Union generals toward first battle

August – September 1861 // Lincoln clashes with Fremont over emancipation in border states

November 1861 // Lincoln elevates McClellan to general-in-chief

January 1862 // Lincoln reorganizes War Dept. and issues Gen. War Order No. 1

March -July 1862 // Lincoln and McClellan argue strategy during Peninsula campaign

July 1862 // Congress adopts Second Confiscation Act and Lincoln secretly drafts emancipation order

August 1862 // Lincoln publicly replies to criticism by Greeley and others

September 1862 // Union victory at Antietam; Lincoln announces both emancipation plans and nationwide suspension of civil liberties

October-November 1862 // Republicans lose seats in midterm elections

December 1862 // Lincoln’s cabinet crisis

January 1, 1863 // Emancipation Proclamation