During the last couple of weeks, students in History 211, “US Elections,” have been studying some of the most dramatic protests for voting rights in American history. They studied the story of parades and hunger strikes for woman’s suffrage. They also learned about the complicated, lengthy struggle to make the Fifteenth Amendment a reality in twentieth-century America. In 2012, CBS News offered a powerful segment recalling one of those moments of struggle –the violence which erupted on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965 at the Edmund Pettus Bridge near Selma, Alabama. After reading Chapters 7 and 8 of Alexander Keyssar’s Right to Vote (2009 ed.), students should be able to identify several elements of this video as being especially teachable for anyone who wants to recall how voting rights and civil rights converged in the mid-twentieth century.

Historian Alexander Keyssar does a good job of dissecting the complicated endgame of the woman’s suffrage movement (though note that Keyssar calls it the women’s suffrage movement –students should consider what the difference in usage implies). This image of a suffrage parade in New York captures many of the issues raised by Keyssar’s narrative in his book, The Right to Vote (2009 ed.). It also highlights many of the key insights of this course, which is why a detail from it appears on the banner image. You can read more about it at the Dickinson Survey of American History. Students interested in this subject might also appreciate two essays from previous iterations of the History 211 course, by Alex Poeton, on the role of women in the Election of 1912, and Ryan Sellinger, on female support for Herbert Hoover in 1928.

Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump will debate three times in 2016, on September 26,

October 9, and and October 19. This is shaping up to be a pivotal series of encounters and yet the story of formal presidential debates is a relatively new one in American political culture. Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas competed against each other for president in 1860, but they didn’t debate, at least not that year. Their famous Lincoln-Douglas Debates were part of the 1858 senatorial campaign in Illinois. In the nineteenth century, presidential candidates barely ventured out int0 the open, let alone debate each other. Douglas did travel and speak in 1860, but Lincoln stayed home in Springfield.

The first real series of presidential debates was in 1960, between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Their televised clash was so famously consequential (and so complicated by FCC rules), that presidential candidates did not debate again in the general election until 1976. They have been debating almost ever since (except in 1980), however, and that is why we know that the Clinton-Trump debates will matter. For the last forty years, these contests have been critical in shaping the decisions of swing voters.

Time magazine online has a good piece from 2015 that documents “10 Memorable Moments” from these debates, including some powerful video clips. The Committee for Presidential Debates also has a helpful reference page outlining the history of American political debates. Students in History 211 should consult these resources before watching the Clinton-Trump series. Prof. Pinsker will be live-tweeting historical context from @House_Divided with the hashtag #hist211. Feel free to join that conversation if you want.

Alexander Keyssar explains the fits and starts of expanding (and sometimes contracting) nineteenth-century American democracy in chapters 2 and 3 of his book, The Right to Vote (2009 ed.). But how best to visualize this complicated story?

Madeleine Gardner offered one valuable approach by trying her hand at creating some infographics based on her notes from Keyssar. All students would benefit from this type of model. Almost every learning study concludes that visualizations help memory. Associating images with facts is the best way to remember them –far better than underlining, cutting-and-pasting, or even rewriting them.

Even if you lack the time to generate charts, graphs, or maps, there’s usually great benefit in simply finding an image online to associate with some kind of textual insight. Consider this famous painting from George Caleb Bingham. It is called “Stump Speaking” (1854), from his trio of paintings on American elections. You can find out more about this series here, but also look below how just combining a striking quotation from Keyssar’s book along with the image helps underscore the interpretation.

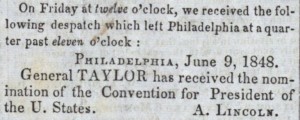

This summer, Democrats met in Philadelphia to hold their national nominating convention. In 1848, the Whigs did the same with Congressman Abraham Lincoln in attendance. Despite a long career in partisan politics, it was Lincoln’s first –and only– direct experience at a national party convention. Yet the story of this moment in June 1848 offers a very teachable window into Lincoln’s own rise to power as well as some key aspects concerning the general evolution of American electoral politics. For the full story, go the “Muster” blog at the Journal of the Civil War Era:

This summer, Democrats met in Philadelphia to hold their national nominating convention. In 1848, the Whigs did the same with Congressman Abraham Lincoln in attendance. Despite a long career in partisan politics, it was Lincoln’s first –and only– direct experience at a national party convention. Yet the story of this moment in June 1848 offers a very teachable window into Lincoln’s own rise to power as well as some key aspects concerning the general evolution of American electoral politics. For the full story, go the “Muster” blog at the Journal of the Civil War Era:

On November 3, 1896, William Jennings Bryan awoke early in Omaha, Nebraska. Looking convivial and relaxed, the Democrat ate a hearty breakfast and headed downtown to travel by train to Lincoln in a regular car. Upon his arrival in the capitol, he was surrounded by supporters, a brass band, and joined a parade through town wtih the popular tunes of “Home, Sweet Home” and “Just Tell Them That You Saw Me” playing in the background. Eventually, Bryan arrived in the Fifth Ward at Precinct F to cast his ballot. Just after 11A.M., he went to place his ballots in their box. A Republican called on everyone present at the polling place to uncover – remove their hats – as a respectful salute to Mr. Bryan and his efforts. The Democrat walked outside and declared, “I have done all that I can.”

Mr. Bryan certainly had. He ran one of the most grueling campaigns in history, traveling six days a week by train, speaking for many hours every day and sleeping for not many hours every night. But from the start, he faced a well organized and much better funded Republican campaign touting their nominee, Governor William McKinley of Ohio. Powerful financial interests flooded Republican campaign war chests encouraged by the specter of a populist president who pledged bimetallism in place of the gold standard. The Republican National Committee spent a staggering $3.5 million (equivalent to $3 billion in today’s money if calculated as a share of GDP), while Bryan and his backers spent only $300,000. Yet historian William D. Harpine cautions against overestimating the importance of money in elections: “Money talks in a campaign,” Harpine writes, “but the money helped McKinley only if the message was persuasive.”

Why were moneyed interests funding McKinley and not Bryan? First, Bryan was a Democrat and a populist who won over many citizen voters by extolling the virtues of the common man and railing against corporations. During one speech, Bryan argued that “The man employed for wages is as much a business man as his employer. The farmer who goes out to toil in the morning is as much a business man as the man who goes on the Board of Trade to gamble in stocks.” He was clearly aligning himself with western and mid-western voters by demonizing northeastern interests (and voters). But, even beyond that, there was something called bimetallism, which was Bryan’s foremost campaign issue. Bimetallism (a.k.a. “Free Silver,” in the words Bryan would have used) would have allowed currency to be backed by silver in addition to gold and would greatly expand the money supply. It appealed to voters because it made more money seem more accessible and their debts more manageable; it scared established business interest, particularly banks, because the increase in the money supply would almost certainly be inflationary and would diminish the value of debt owed to them. One Republican poster suggested that free silver would mean prosperity at the level of Guatemala.

Unfortunately for Mr. Bryan, doing “all [he] could” was not enough to win the presidency. The third party “National Democrats” who strongly opposed free silver probably split the Democratic vote and helped Republicans win in states like California and Kentucky. Wealthy and powerful interests donated immense amounts of money to McKinley and the Republicans, and they eventually won out.

That night, Bryan went to sleep defeated but not broken. He would proclaim: “The friends of bimetallism have not been vanquished; they have simply been overcome.” Bryan remained a dominant voice in the Democratic party, shaping the party’s platform and winning the nomination once again four years later, free silver in tow.