This post offers an example of how to transform initial reading into some thoughtful first steps toward a paper topic.

By Emma Jenkins

Benjamin Franklin’s contributions to the 1787 Constitutional Convention were often out of place. Perhaps his most insightful observation was on Monday, September 17th, as the delegates gathered to sign the Constitution after four long months. He astutely remarked that when “you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views. From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?” [1] He was right. While the Constitution was a revolutionary document, it was far from perfect.

Instead, the document signed that crisp fall afternoon reflected how the delegates were divisive on major issues like presidential power, impeachment, apportionment, and slavery. Rather than interrupting the Convention’s momentum to harp on controversial topics, the delegates either glossed over these issues or eventually passed them off to the states. While all of these topics were hotly contested, slavery was the issue that continuously plagued the Convention that summer. After months of back and forth, the delegates finally decided to let each state choose whether to abolish slavery and the slave trade. However, the Framers wrote into the Constitution multiple clauses that protected so-called state interests without ever using the words “slave” or “slavery.” This is the source of one of history’s most debated issues: was the United States Constitution a pro- or an anti-slavery document? This question is open to many interpretations, especially because historians can only speculate about the Framers’ original intent. Were they institutionalizing slavery at the national level, conceding to southern state interests and expecting slavery to fizzle out, or were they attempting to undermine it altogether? Whatever their intent, the pro-slavery clauses in the Constitution allowed the institution to continue – and now it was on the national stage.

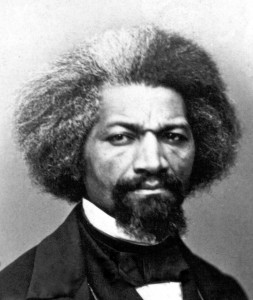

This debate is not new – it was a popular topic for 19th century abolitionists Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison – and has resurfaced after presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders claimed the United States was “created … from way back on racist principles.” Historian Sean Wilentz responded in a New York Times op-ed, arguing that Sanders’ belief “is one of the most destructive falsehoods in all of American history.” He makes a good argument that the Constitution was an anti-slavery document, but I’m not entirely convinced. He claims, for example, that “Without that antislavery outcome in 1787, slavery would not have reached ‘ultimate extinction’ in 1865.” However, I believe that the Constitution temporarily allowed the institution to continue. And while it’s difficult to determine the Framers’ original intent, historian David Waldstreicher makes a compelling argument in response to Wilentz. He insists that the Framers’ Constitution wasn’t an anti-slavery document and points out that of “the 11 clauses in the Constitution that deal with or have policy implications for slavery, 10 protect slave property and the powers of the masters.” Yes, many of the Philadelphia Convention delegates knew that slavery was wrong. Pennsylvania’s Gouverneur Morris even went as far as to call it “a nefarious institution.” [2] But that didn’t mean the delegates (all of whom were white men, and many of whom were elitist) were ready to abolish slavery and accept African Americans as equals. The harsh fact of the matter is, in Wilentz’s words, “most white Americans presumed African inferiority.”

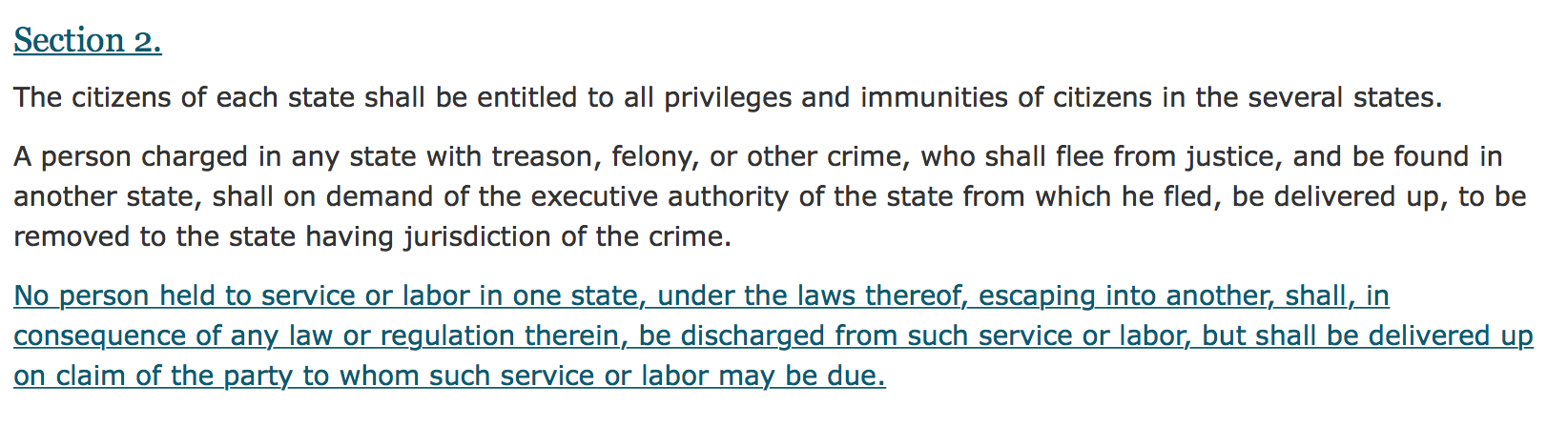

So, the Framers wrote a document that reflected the sentiment in 1787: many realized slavery’s hypocrisy in the land where “all men are created equal,” but they were crippled by their “inability to imagine free blacks as equal citizens.” [3] The delegates left the wording vague because they didn’t know how to handle the issue. However, it’s indisputable that the Constitution allowed slavery to continue. It prevented Congress from amending the slave trade clause before 1808, and it didn’t even set a date to reconsider the fugitive slave clause. Waldstreicher’s assertion that “the Constitution was deliberately ambiguous – but operationally proslavery” perfectly summarizes my argument. Take the fugitive slave clause, for example. The wording is obscure but the meaning is explicit. It acknowledged the institution of slavery on the national level but left enforcement to the states. Even worse, it “was not merely a provision that passively countenanced slavery, but, rather, it was one that required those states where slavery had been abolished to be actively complicit in keeping slaves in bondage” [4]. As James Madison reflected in 1792, “Every word … decides a question between power & liberty.” While the words “slave” and “slavery” were intentionally excluded from the Constitution, there’s no question that these clauses gave power to white citizens and took away liberty from slaves.

But as Franklin asked, “From such an assembly can a perfect production be expected?” [5] While there were faults with the Framers’ Constitution – largest among them the national institutionalization of slavery – it was a product of the time. Slavery was commonplace and the delegates simply believed that Americans weren’t ready to accept, and couldn’t envision, African Americans as equal citizens. I don’t believe the Framers intended slavery to continue indefinitely, but they permitted it to carry on for the moment because they didn’t want the Union to crumble over this issue.

I expect this debate to generate a final paper topic. It’s a good starting point because it’s a controversial topic and the 2016 presidential election has brought it back in the spotlight. Going forward, I’d like to explore how these clauses ignited the great debate between the North and the South, and how different Constitutional interpretations led to sectional crisis and the outbreak of war.

[1] Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (New York: Random House, 2009), 360.

[2] Ibid, 316.

[3] Ibid, 323.

[4] Ibid, 330.

[5] Ibid, 360.

Received, thanks