At first, the New Edinburgh Dispensatory appears dislocated from modern scientific relevancy. My email to a Dickinson science history professor before the bulk of my research started yielded no title recognition from her (Pawley). However, though the Dispensatory was not placed within a relevant book list, I was told that Edinburgh was a scientifically significant location at the time of its release, giving the first hint to this book’s place in a larger historical continuum after further research (Pawley). This theme does not stop there, though, as the people and knowledge behind the production and transport of the book have significance, even if the content does not. The most immediate link to this theme lies in the way the book was donated to Dickinson in the first place.

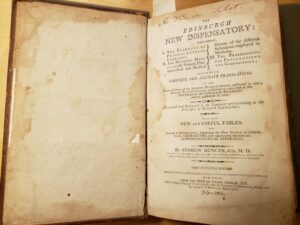

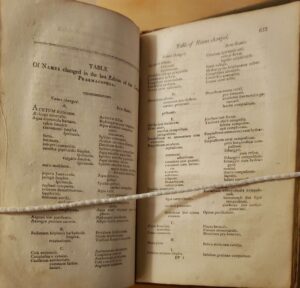

Figure 1- Donation Inscription and Date of Sale

Despite being noted as originally owned by Joseph van der Schot, the donation inscription also states that the donor was one Frank R. Keefer (Figure 1). However, all that is known about van der Schot from Dickinson records appears on the inscription within the book, describing his career as a military surgeon who died in service at Pittsburgh in 1805 (Figure 1). Interestingly, though morbidly, the above seller’s inscription cites 1805 as the sale year, meaning that we can infer that van der Schot must have possessed this book for only a brief time. The manner of his death is unknown, but probably unrelated to his service in the military, since early 1800s Pittsburgh was in an industrialization stage, not a combat one (“Pittsburgh”). Still, van der Schot is not the only relevant personal figure associated with this book.

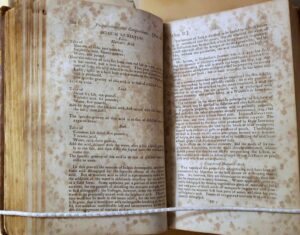

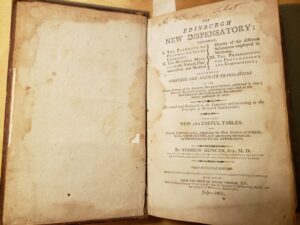

Figure 2- Dedication from Andrew Duncan to his father.

Keefer’s life expands the story. Joseph van der Schot was Frank Keefer’s maternal great-grandfather, so this specific Dispensatory must have been an inherited family keepsake (Figure 1). My February interview with Dickinson archivist Malinda Triller Doran helped fill in the gaps in Keefer’s life. In addition to graduating as part of Dickinson class of 1885, Keefer was an “M.D.” at time of donation. Just like the author Andrew Duncan’s dedication to his doctor father, a family legacy of medicine was something also perhaps implicitly passed down (Figure 2). We also know the book was officially donated and processed on February 17th, 1950, based on archival records, meaning the book was in his family line for almost 150 years before donation (Figure 3). Keefer also donated books from his personal collection such as Military Hygiene and Alcoholic Drinks and Narcotics in 1952 (Malcolm). A November 1925 Dickinson Alumnus profile shows Keefer reflecting on his comparatively storied military career to what we know of van der Schot (“Ranks” 8-9). Still, Keefer and his great-grandfather’s military service implies a legacy in this family line, especially considering both served in medical capacities. However, a caveat must be made that the finer details relating to the emotional dynamics of this book are likely lost forever. For example, even though van der Schot only had this book a short time before death, there is no record as to whether this book was a treasured family keepsake lovingly passed down throughout the decades, or merely something left to grow dusty in an attic until the Keefers did some spring cleaning and decided to donate. We cannot know that, but the familial line alone tells us about how this book has traveled throughout the ages based upon a continuing familial line and legacy.

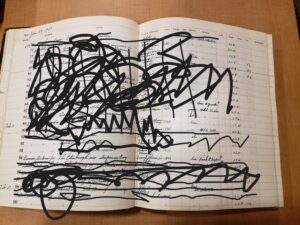

Figure 3-(Donations aside from Dispensatory crossed out for privacy)

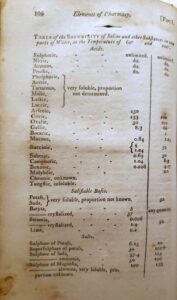

Scientific legacies of mutable terminology and practice also represent another throughline of history within the Dispensatory. Page 5 in the “Epitome of Chemistry” section, for instance, discusses how radiation is a method to “repel” certain “particles of caloric” (Duncan 5). In other words, the Dispensatory states that heat can be transmitted through waves. Though we may associate the term “caloric” with calories today, the quote context signals the 18th century connotation of heat (“Caloric”). Similarly, the first modern use of X-ray radiation in 1895 was not discovered until almost a century after the Dispensatory’s publication (Fröman). The usage of radiation in the Dispensatory instead points to an older (and more obvious) definition describing “emissions of rays” or heat (“Radiation”). Thus, while technically correct even today, the terminology marks the content squarely as part of the past. On a similar note, there are many elements within the text, but their true significance and usage would not be realized until much later. For example, uranium’s short description calls it an “incoherent mass” and then briefly mentions its hardness and basic combinative potential (Duncan 27). Once again, the content is technically correct, but not in the same context we would describe how to handle uranium today.

However, the Dispensatory’s most important representation of its continued scientific relevancy is its handling of the demonstration of science itself. From a commercial standpoint, a bookstore today selling a medical textbook that gives advice on deadly poisons and remedial balms would be unlikely. (Duncan 491-503). Still, the principles behind these actual recipes are still used practically today, even if some of the ingredients themselves are different. In the “Preparations and Compositions Section” concerning lead, the book gives instruction to “entirely…[reject]” ingestion (Duncan 476). Yet, it still advertises lead’s usefulness in treating external skin ailments (Duncan 476). While the lead in everyday life has declined significantly, using harmful materials for a greater destructive purpose remains a part of modern medicine like with chemotherapy (Pedersen, “Lead”). Despite chemotherapy’s proven negative effects, the continued usage reflects a similar principle to that found in the Dispensatory in which medicine does the best with the knowledge available at that moment in time (“Chemotherapy”).

While some of the Dispensatory’s content may be obsolete, the scientific and personal history found within still has relevancy. We now understand that lead should not be applied to the skin, but similar philosophies of taking the lesser evil are still present in modern medicine. At the same time, the Dispensatory’s personal history with the Keefers and van der Schots further shows how real people also continue and pass down legacies of knowledge, occupation, and blood to newer generations. In short, taking all the Dispensatory’s information to heart may not be productive because of the outdated content. Instead, appreciating the mindsets and continued legacies, whether personal or scientific, provides the key to understanding the Dispensatory’s rich nature.

Works Cited:

“caloric, n.” OED Online, March 2023, www.oed.com/view/Entry/26508. Accessed 30 March2023.

Dickinson College Library. Accessions ledger 70001-80000, January 12, 1949 to October 19,1953. Record Group 4/51 Library, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

Duncan, Andrew. The New Edinburgh Dispensatory. Worcester, 1805.

Fröman, Nanny. “Marie and Pierre Curie and the discovery of polonium and radium.” NobelPrize Outreach AB 2023, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/themes/marie-and-pierre-curie-and-the-discovery-of -polonium-and-radium/. Accessed 30 March 2023.

“How Chemotherapy Drugs Work.” American Cancer Society, 2023, https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/treatment-types/chemotherapy/how-chemotherapy-drugs-work.html. Accessed 30 March 2023.

Malcom, Gilbert. Letter to F.R. Keefer. Received by Frank Keefer. 25 June 1952.

Pawley, Emily. “Re: Book Relevancy.” Received by Anna Robison, 27 March 2023.

“Pittsburgh Becomes the City of Steel.” PBS, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/foster-pittsburgh-becomes-city-steel/. Accessed 30 March 2023.

Pedersen, Traci. “Facts about Lead.” LiveScience¸ 6 October 2016, https://www.livescience.com/39304-facts-about-lead.html. Accessed 30 March 2023.

“radiation, n.” OED Online, December 2022, www.oed.com/view/Entry/157243. Accessed 29 March 2023.

“Ranks High in Army Medical Service.” The Dickinson Alumnus. November 1925, pp. 8-10.

Triller Doran, Malinda. Personal Interview. 10 February 2023.