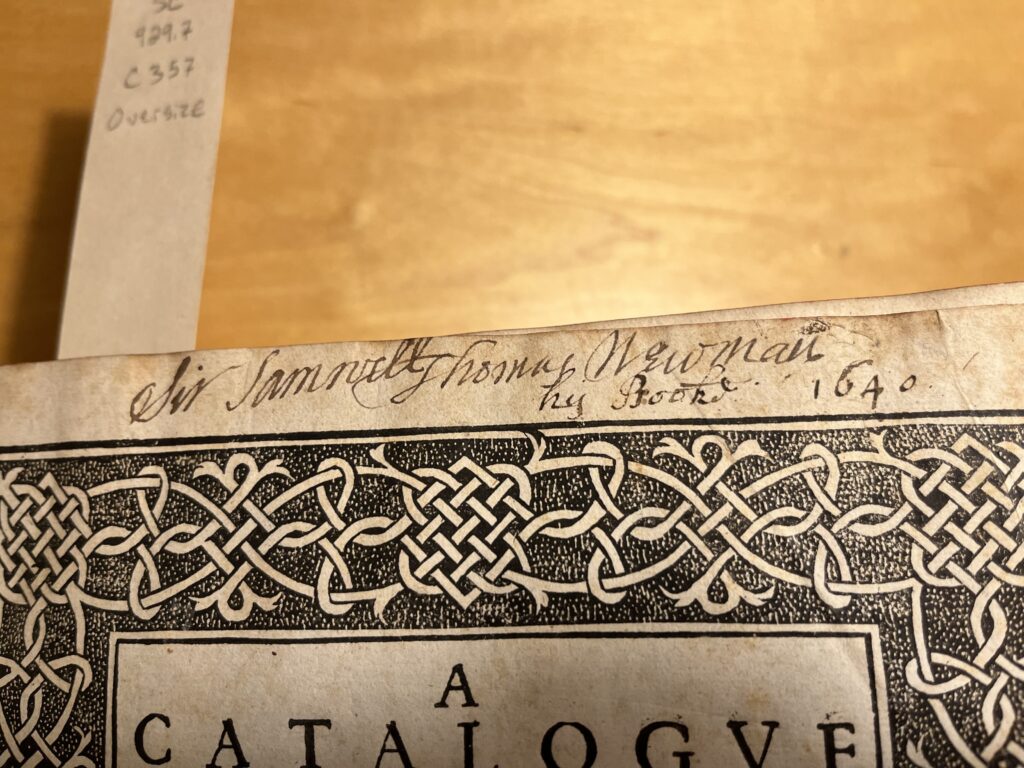

This book, as previously established, does not seem like an edition belonging to those where “The historie of foure-footed beastes” and “The historie of serpents” were published jointly in 1658. In consulting archivist Malenda Triller, I learn that the most plausible way for two books published and printed a year apart to be included in the same codex is that a private individual had them bound into a single one. Reasons such as admiration for both works, the pragmatism of keeping two volumes in one place, faster consultation, or even the guarantee of equal preservation of the manuscripts might be considered, but the true motivations why this was done are unknown, as is the identity of the hypothetical individual who had Topsell’s two works bound together in the same volume. The inscription of a name –Jonathan Yates – and a date –1660– on the first page that we do preserve of the first book might be a piece of potential evidence that could give us more answers to the mistery of the individual who bound both books.

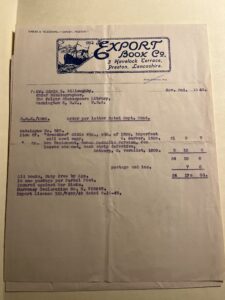

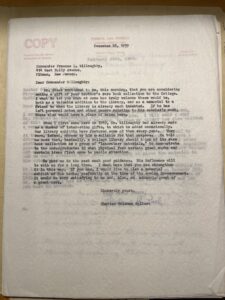

The mystery about the first owner who brought the two books together is not solved either by looking at information about the book’s most recent owner, before it came to the Dickinson College Special Collections Archive. And that is because, although the book arrived here as part of a donation from the Willoughby family, in which many other books from this former professor and scholar were offered to the college library for better preservation, after his passing, often, explained Malinda Triller, an ever-helpful librarian, donated books come with a record with information about their acquisition, their history, or some other piece of information such as the price for which they were purchased, but not in this case.

Going back to its origins and realizing that these are two books from different periods in the same volume, I pay even more attention to the front and back matters, which usually include information for the reader (dedications, epilogues, etc.). I do this in order to focus on learning more about the book, its afterlife and the way it was received. In other words, to better understand the book in its contemporaneity. For example, in the first “Epistle to the Learned Readers”, Topsell states that this book was conceived “to shew to euery plaine and honest man, the wonderfull workes of God in every beast in his vulgar toongue, and giue occasion to my louing friendes and Country-emn, to adde of themselues, or else to helpe mee with their owne obseruations vppon these stories”. Again, in “An Epilogue to the Readers”, I find that the author insists on asking its readers for their collaboration to continue expanding the book. He does it for a very important reason: the more collaboration in this work, the greater the glory for all English speakers, for never before has such an extensive work been written in vernacular English.

If you think my endeauors and the Printers costs necessarie and commendable, and if you would euer farther or second a good enterprize, I do require al men of conscience that shall euer hear, read, or see these Histories, or wish for the sight of the residue, to helpe vs with knowledge, and to certifie their particular experiences in any kinde, or any one of the liuing Beastes: and withall to consider how great a task we do vndertake, trauelling for the content and benefit of other men, and therefore how acceptable it would be vnto vs, and procure euerlasting memorie to themselues, to be helpers, incouragers, ayders, procurers, maintainers, and abettours, to such a labor and needefull endeuour, as was neuer before enterprized in England. (Y y y 2, The Historie of foure footed beastes).

In the front matter of the second book, however, Topsell writes about other issues regarding the reception of the first book. For example, two printing errors in the first book are amended and the translations of certain Latin verses that complicated comprehension are deleted.

Therefore, what we now know from the book is that its reading dignifies souls as would the contemplation of a divine work, and that Topsell had a clear intention to extend this text, to create an unprecedented scientific basis for zoology in the English language.

Despite the fact that it is not the 1658 edition and no other editions of this work are known to us, neither expanded nor revised, Topsell’s work has had an enduring life with much to be squeezed out.

For one, his project –even though he didn’t succeed in finishing it before his death– was crafted and first published (in 1607 and 1608) in the midst of important events for the scientific world, as John Lienhard points out in his brief description of these books. According to Lienhard, “his monumental work was actually an early glimmer of modern science” (Topsell’s Beasts), and therefore constitutes an exemplary work attempting to get closer to what we nowadays understand by “zoology”. The content of the book was, in its origins, according to the author, already relevant and dignifying to its reader not only because of the wealth of knowledge contributed by Conrad, but also because what Topsell proposes is a contemplation of the divine creation in a language that was no longer Latin.

The very dignifying content in this work, however, did not mature well over time. For instance, one does not believe nowadays the following description of the way in which mice procreate: “The generation or procreation of Myce, is not onely by copulation, but also nature worketh wonderfully in engendering them by earth and small showers” (The Historie of Foure Footed Beastes, Of Wilde Myce), or that “It is also very certaine that Mice which liue in a house, if they perceiue by the age of it, it be ready to fall downe or subiect to any other ruin, they foreknow it and depart out of it”, found in a passage subtitled “Presages and forknoledge of mice”, nor is it nowadays conceived a book of knowledge about animals to additionally include indications for natural remedies, medicines, spiritual or fantastic matters, such as long descriptions of the types of horns a unicorn may possess.

What makes it rare, not just because of its binding, but concerning its content, is precisely these out-of-date conceptions of nature, of authority, and moreover the evidence of a quest for objectivity, which is demonstrated by the extensive documentation used to talk about the creatures, in the midst of so much fantastic information about mythical creatures. Now considered obsolete, what brings us closer to this nearly 1000 page-long compilled volume of wisdom is the possibility offered by the work to immerse ourselves in the study of the natural world as it was understood in the seventeenth century, of reasoning, of the limits (or lack thereof) between truth and fiction, documentation and objectivity, of the weight of authors’ references versus what they themselves know or can attest to through their own experience (or, again, lack thereof).

Works consulted:

“Topsell’s Beasts” Engines of Our Ingenuity. Houston Public Media, 2000. John Lienhard, University of Houston. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1586.htm

Isaac, S. (2018, March 16). The familiar and the fantastic: The Historie of Foure-Footed beastes by Edward Topsell, 1607. Royal College of Surgeons. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/the-familiar-and-the-fantastic/

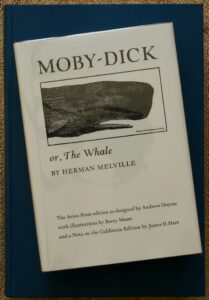

to indirectly engage in conversation with the audience (as seen in the front matter pictured here). This librarian is a thinly disguised representation of himself, considering he compiled the thorough references to whales (touching on their symbolic meaning that will be expanded upon) in past literature. However, at the time of publication, the public was widely unaccepting of

to indirectly engage in conversation with the audience (as seen in the front matter pictured here). This librarian is a thinly disguised representation of himself, considering he compiled the thorough references to whales (touching on their symbolic meaning that will be expanded upon) in past literature. However, at the time of publication, the public was widely unaccepting of