For any readers just joining me, this is my third and final blog post about Ralph Brooke’s 1619 Catalogue. My first is a general introduction, and my second combines analysis of the book’s origins and afterlife. Here, I turn to the book’s provenance.

When Dickinson acquired the Catalogue, any papers establishing its provenance did not come along with it. While we do have some of the receipts from Edwin Willoughby’s purchases between 1943 and 1949, none of these documents mention the Catalogue. That has made the job of reconstructing the book’s provenance rather difficult. What follows is my best attempt; I have had to make several key inferences even to get to this point.

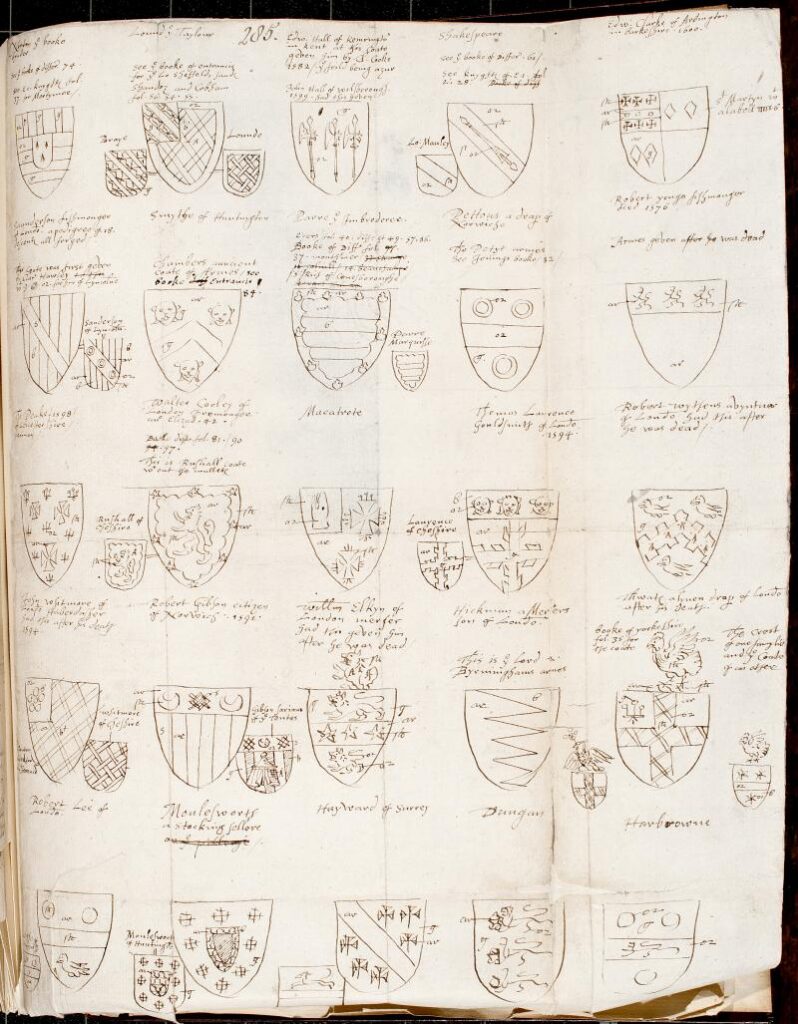

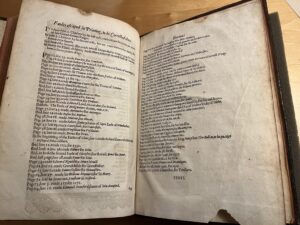

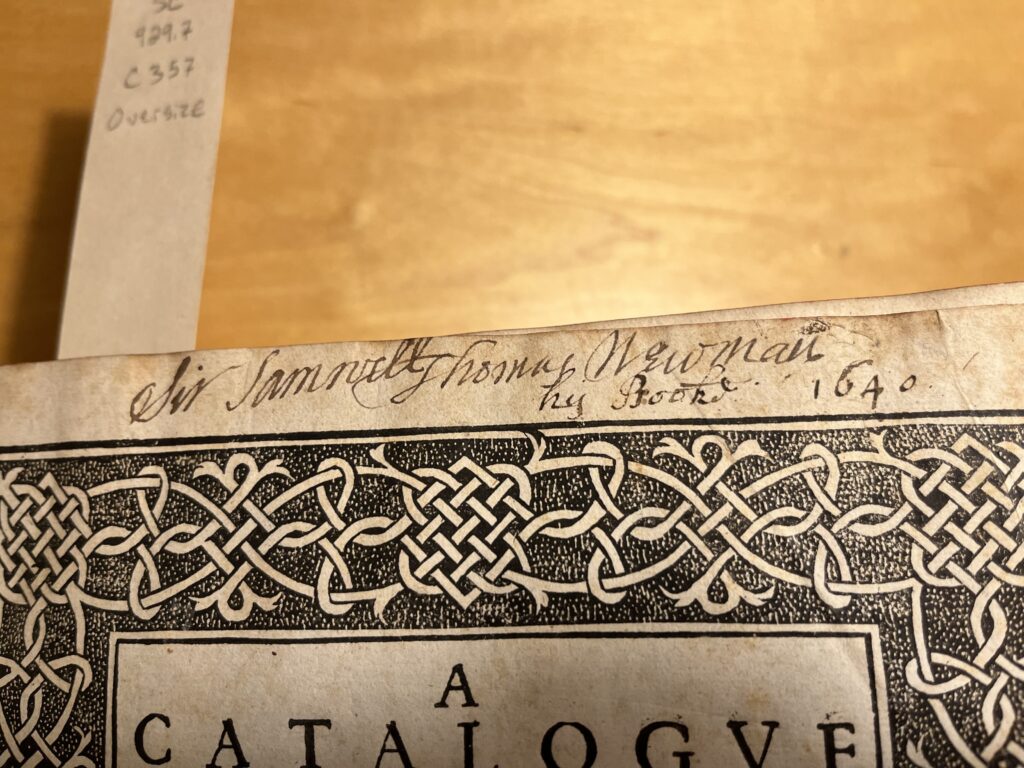

I think I have gained two writers for the price of one. In an earlier post, I identified the inscription on the title page (fig. 1) as a single name, “Sir Samwell Thomas Newman,” but this mystery knight seemed not to exist. Recently, though, I noticed that the ink, the alignment, and the letterforms appear to differ subtly but significantly between the phrases “Sir Samwell” and “Thomas Newman his booke 1640.” While I have received conflicting second opinions about bifurcating “Sir Samwell Thomas Newman,” I think it is worthwhile to entertain the possibility that the two parts of this inscription refer to two separate people, and I have chosen, not without evidence, to treat them as such for the purposes of this post.

Fig. 1: the inscription on the title page.

Christopher John Edwin Newman, a modern-day member of the family, has made a website cataloguing the family history of the Newmans of Fifehead in Dorset, and when we consider the possibility that there are two inscriptions, first by Thomas in 1640 and then later by Sir Samwell, a coherent timeline of family ownership emerges. Two Thomas Newmans, in fact, were alive in 1640, one who died in 1649, and the other, his son, who died in 1668 (C. Newman). Our Thomas Newman could be either; regardless, the timeline works. Sir Samwell Newman, on the other hand, lived from about 1696 to 1747 (C. Newman). His first name, Samwell, is his mother’s last name, and the Samwells and Newmans had not intermarried before then, so it is very unlikely indeed that a yet-unrecorded Samwell Newman even could have existed in 1640. His title “Sir” only makes the possibility of some shadowy 17th century Samwell more unlikely: the Newmans were only granted a baronetcy under the real Sir Samwell’s father, Richard, in 1699 (C. Newman).

The binding also offers clues. Both the front and back covers have been blind-stamped with the letters “TN,” who (if these are initials) very easily could be one of the two Thomas Newmans I have already mentioned (fig. 2). Thomas Newman was certainly not averse to marking up his books. Since the Newman Family Tree’s catalogue only lists two Thomases under the first initial T, identifying TN as Thomas Newman would conclusively date the binding to the seventeenth century. This timeline also raises a major question, though: why are the many annotations throughout the text cut off by the edge of the page? There are, I think, two possibilities. First: the book may have already been annotated by a prior owner in a cheaper binding before it came secondhand into Newman’s possession. Second, Newman could have annotated it himself prior to sending it to a bookbinder. My examination of the book yielded none of the telltale holes that stab-stitching leaves, but these can be difficult or impossible to find in a book that has been rebound.

Fig. 2: The back cover, blind-stamped with “TN.”

This book’s binding has also helped me fill in the gap after the Newman family and before Edwin Willoughby. At some point in the mid-nineteenth century, and certainly after 1831, our book came into the possession of Robert Dundas Duncan, 1st Earl of Camperdown, whose gilded armorial stamp can clearly be seen on the front cover (fig 3). How this book made its way from the West Country to Scotland eludes me, and any efforts to establish whether the Newmans and the Duncans intermarried have been unsuccessful. While my dating of the binding to the seventeenth century is tenuous without expert opinion, the presence of the Camperdown stamp on the front cover definitively dates the binding to the mid-nineteenth century or before.

Fig. 3: The front cover, stamped both with “TN” and with the seal of the Earl of Camperdown.

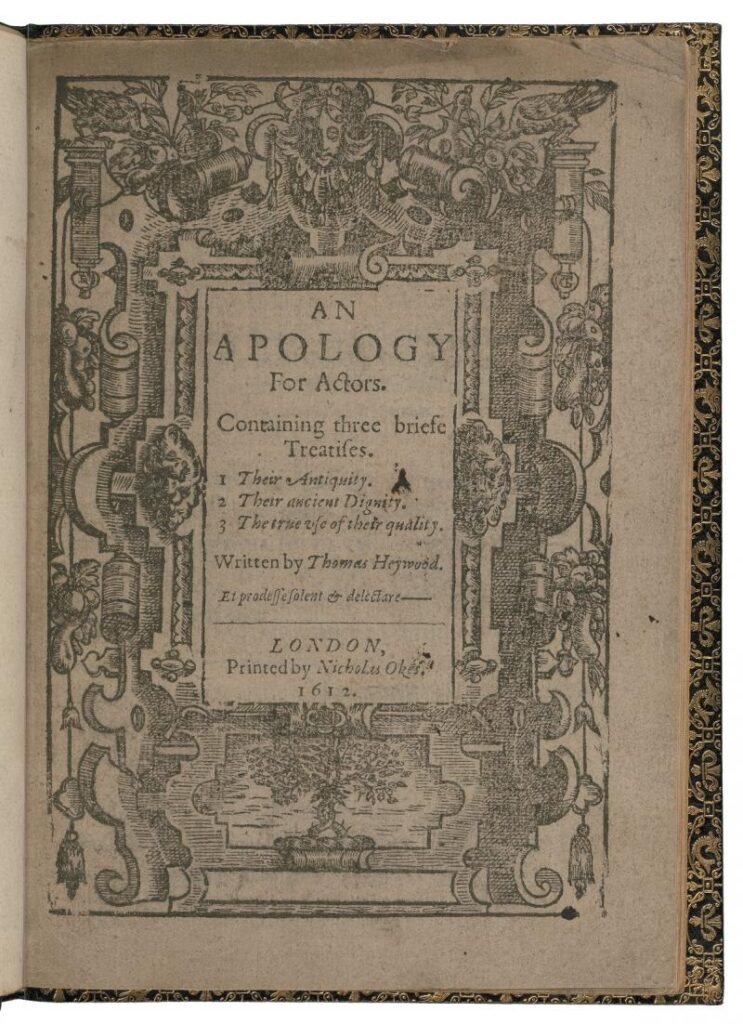

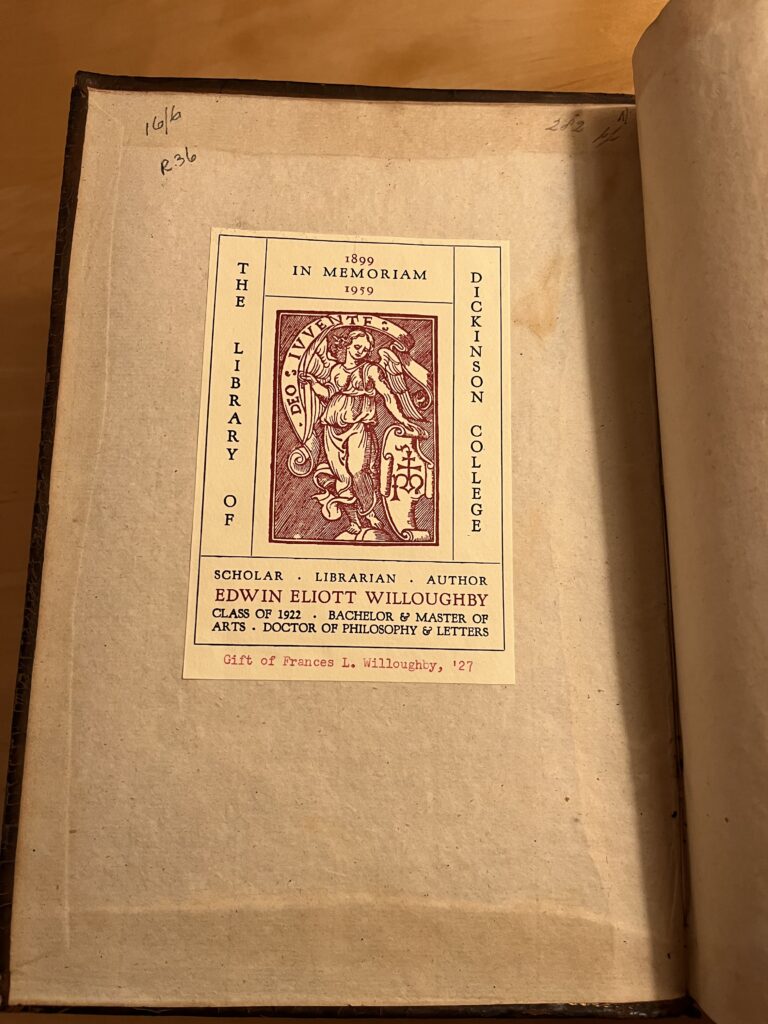

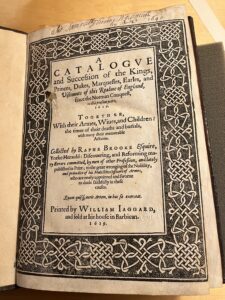

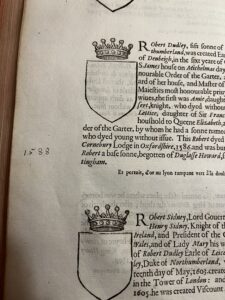

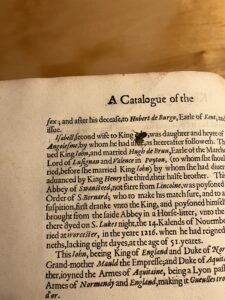

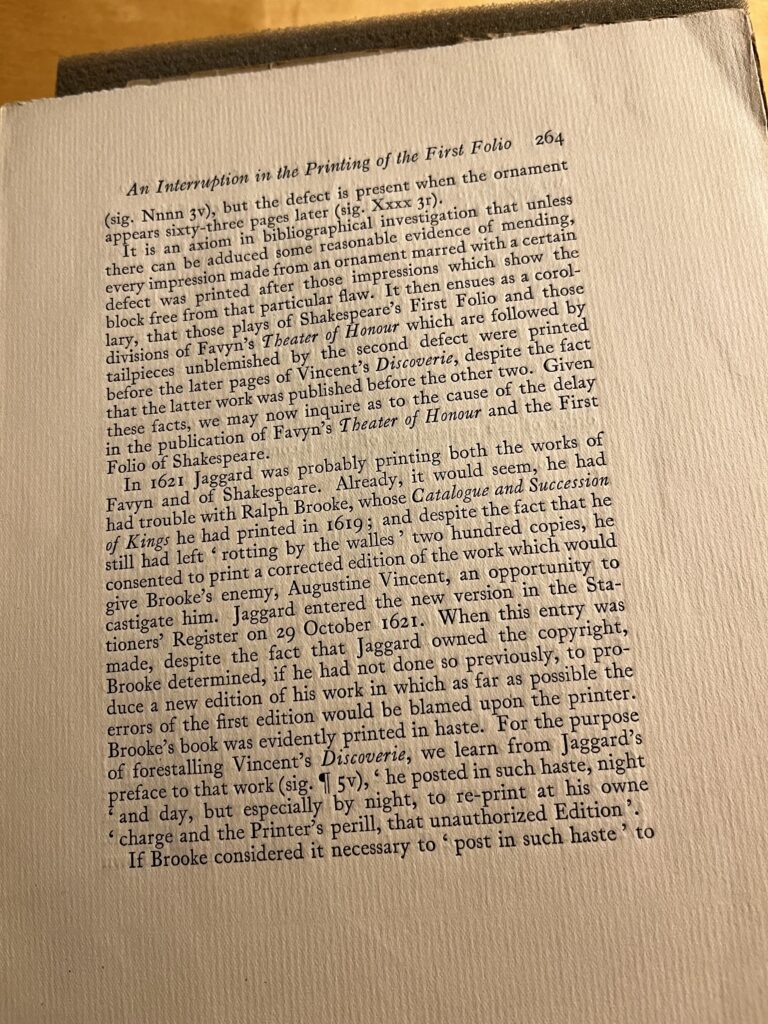

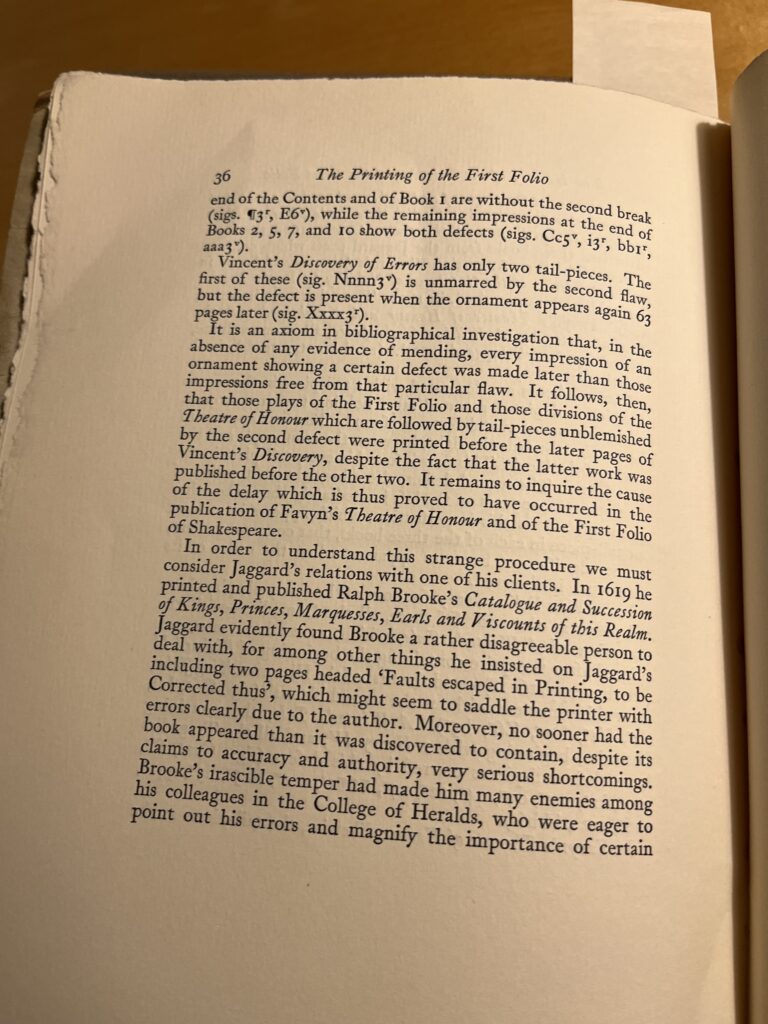

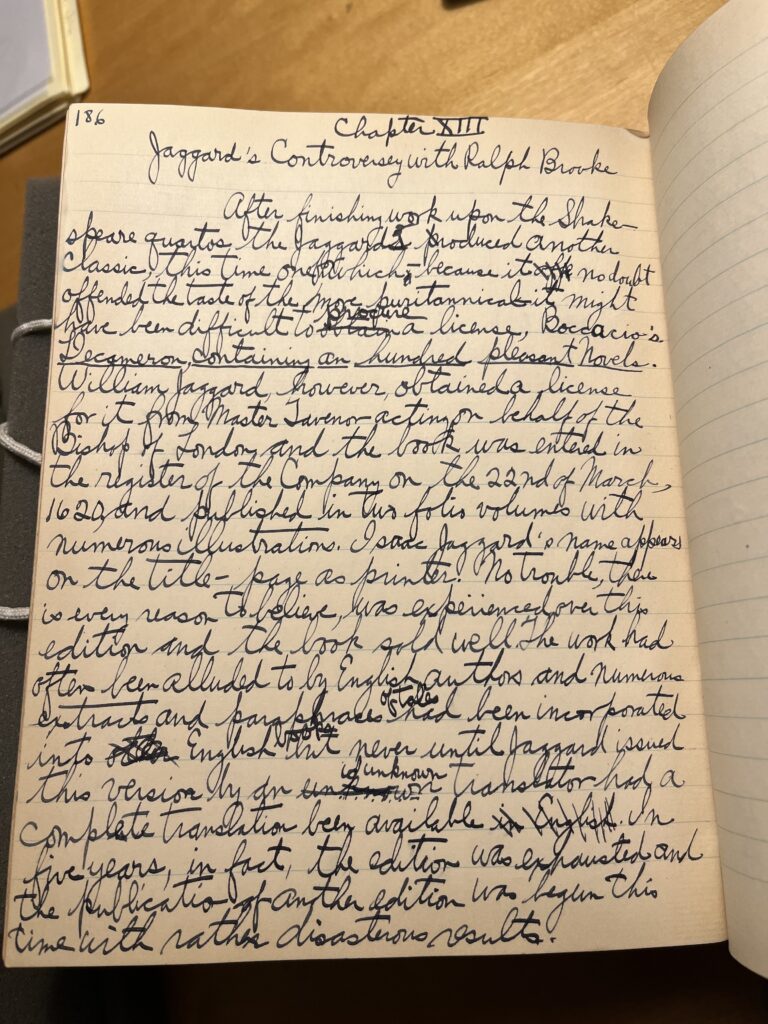

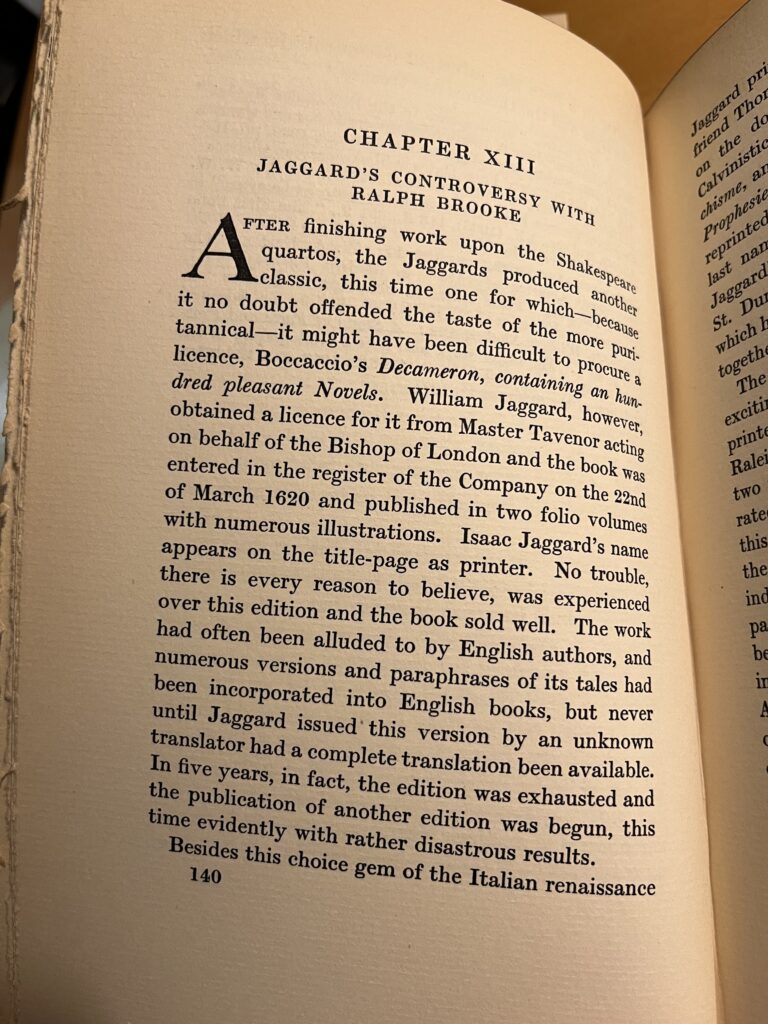

I mischaracterized Edwin E. Willoughby as a mere collector in my previous posts. Dickinson’s archive possesses many of his private documents and his publications, and these make it immensely clear that he had far more than a passing interest in the Catalogue. Willoughby, in fact, returned to the Catalogue several times in his publications, particularly because the Brooke-Jaggard dispute affected the schedule of the printing of the First Folio. In 1928, in graduate school, he wrote a five-page piece entitled “An Interruption in the Printing of the First Folio,” where he tracks the delays in the production of the Folio; a relevant section concerns the delay that Brooke caused (fig. 4). Four years later, Willoughby wrote The Printing of the First Folio of Shakespeare, which expands on the themes in “An Interruption” and discusses the difficulties between Jaggard and Brooke (fig. 5). Finally, in 1934, he published a biography of William Jaggard entitled A Printer of Shakespeare: The Books and Times of William Jaggard. I have had the opportunity to study both his handwritten drafts (fig. 6) and a printed copy (fig. 7).

Fig. 4: The section of “An Interruption” covering the Jaggard-Brooke conflict.

Fig. 5: A mention of Brooke in The Printing.

Fig. 6: Willoughby’s handwritten draft of the beginning of Chapter 13 of A Printer.

Fig. 7: The printed first page of Chapter 13 of A Printer.

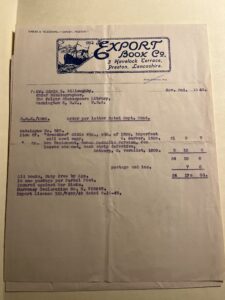

Brooke’s Catalogue was clearly relevant to Edwin Willoughby’s research interests, and that is evidently why he owned it. What remains unknown to me, however, is when the Catalogue actually came into Willoughby’s personal possession. While it seems possible that he purchased it to aid his research while working on one of his pieces written during the 1920s and 1930s, I’ve noticed an inscription in in the back of the book: “F. 11.1.43” (fig. 8). To me, that indicates a date: either 1 November or 11 January 1943. Inscriptions of this type or in this hand are nowhere in all other Willoughby books that Special Collections Librarian Malinda Triller-Doran and I checked in the archive, which leads me to believe that Willoughby may not be the writer; he would have purchased the book, then, at some point during or after 1943. We do have a book order from November 1943, addressed to Willoughby from The Export Book Company in Preston, Lancashire, but this mentions only two Bibles from the turn of the 17th century (fig. 9).

Fig. 8: The mysterious 20th-century writing in the back of the Catalogue.

Fig. 9: An invoice from the Export Book Company to Willoughby regarding two Early Modern bibles.

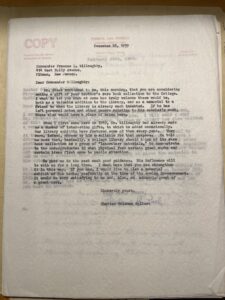

Edwin Willoughby died in 1959, having never married. His sister, Cmdr. Frances Willoughby—an extraordinary figure in her own right, whose achievements included becoming the first woman to permanently achieve the rank of commander in the United States military—donated many of his books and papers to Dickinson after his death (fig. 10), and the College held an exhibition of his collection in his honor. The book has remained in our archives since then. I hope that some of its yet elusive mysteries are eventually solved, but I am grateful to have filled the amount of missing information I have.

Fig. 10: A letter from Charles Coleman Sellers, Librarian of Dickinson College, to Frances Willoughby.

Works Cited

Brooke, Ralph. A CATALOGVE and Succeſsion of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marqueſſes, Earles, and Viſcounts of this Realme of England, ſince the Norman Conqueſt, to this preſent yeare, 1619. London, William Jaggard, 1619.

“Duncan, Robert Dundas, 1st Earl of Camperdown (1785 -1859).” British Armorial Bindings, University of Toronto Libraries, armorial.library.utoronto.ca/stamp-owners/DUN002.

“Edwin Eliott Willoughby (1899-1959).” Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, 2005, archives.dickinson.edu/people/frances-lois-willoughby-1906-1984.

“Frances Lois Willloughby (1906-1984).” Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, 2005, archives.dickinson.edu/people/frances-lois-willoughby-1906-1984.

Newman, Christopher John Edwin. Newman Family Tree, 25 Dec. 2022, www.newman-family-tree.net/.

Sellers, Charles Coleman. Letter to Commander Frances Willoughby. 28 December 1959. Edwin E. Willoughby file. Archives and Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Carlisle, PA.

The Export Book Company. Invoice to Edwin Willoughby. 2 November 1943. Box 4, folder 12. Edwin E. Willoughby papers. Archives and Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Carlisle, PA.

Willoughby, Edwin E. A Printer of Shakespeare: The Books and Times of William Jaggard. London: Philip Allan & Co., 1934.

—. Handwritten draft of A Printer of Shakespeare. Box 1, folder 3. Edwin E. Willoughby papers. Archives and Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Carlisle, PA.

—. The Printing of the First Folio of Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1932.