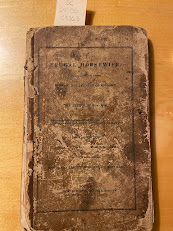

A twentieth edition of The American Frugal Housewife by Lydia Maria Child (penned Mrs. Child), published in 1836, originally caught my eye due to its title and binding. To start, the binding of the book is wrapped in patterned cloth (Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2

The cloth is thin and where it is frayed reveals the material of the binding underneath cardboard in fine paper or leather (Greenfield, 109). Due to the cloth covering, it was challenging to determine what the cover was made of upon first examination. However, I was fortunate enough to examine an earlier edition of this book also housed in the Dickinson College Archives (an eighth edition printed five years earlier; Figure 3).

Figure 3

This edition is not bound in cloth and appears to be made from compressed layers of cardboard. This led me to assume that the cover from the twentieth edition was made similarly, if not exactly. The comparison also raised the question of how the cloth cover came to be on the book. It looks homemade, with loose stitches and stings crossing over the inside cover, where the cloth is glued down (Figures 1 and 2). Was it sold that way? Was it a special edition? Did a previous owner sew on a decorative covering?

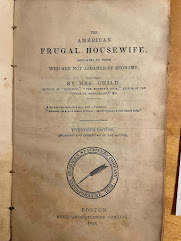

The title of the book also caught my attention. The term “American Housewife” seems misogynistic now, although in the context of the 19th century the term was seen as socially acceptable. The author was also simply credited as “Mrs. Child,” emphasizing her marriage and husband’s last name. However, upon further research I was surprised to discover that Lydia Maria Child was an abolitionist, Native American Rights activist, and Women’s Rights activist (“Lydia Maria Child,” 1). Her work was successful and had an influence on the general masses. This could be in part because she was a well-known author before publishing this book; her name was recognizable and could have aided in book sales. The book focuses on providing information and tips for moderate and low income households that did not employ staff. A motivation for authoring this book could be accessibility in providing the lower classes with a range of information from cooking to teaching your daughter proper etiquette and learning about herbs and remedies.

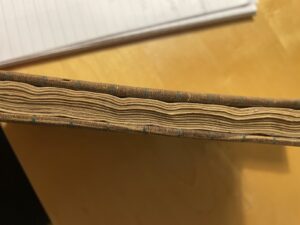

The book was published in Boston by the American Stationers’ Company and has thirty-two editions (“American Frugal Housewife,” 1). There is no editor listed. There are 132 pages, including front matter, an index, and a torn blank sheet (Figure 4).

Figure 4

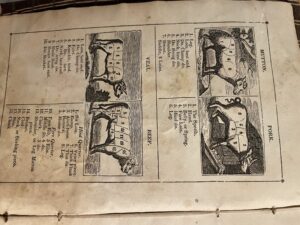

The only front matter the book contains is an introduction chapter, a title page with a black and white publishing logo, and a black and white illustrated diagram of four animals, bodies cut into sections and numbered, with corresponding labels explaining the location of different cuts of meat (Figures 5 and 6).

Figures 5 and 6

After having met with the Dickinson College Archivist Malinda Triller-Doran, I made an educated guess that the paper used is rag-based. Cloth based paper was popular in the early 19th century, with pulp-based paper becoming more mainstream in the mid 1800s as a cheaper alternative (Valente, 2). I think the paper is rag-based due to the date of publication, the lack of noticeable pulp, and the texture. Pulp based paper normally gets brittle with age and moisture, and while there is some water damage present (Figure 7), the paper itself remains in good quality.

Figure 7

In the beginning of the book there is a note that the title was changed to include the word “American” to distinguish it from an English version with the same title for copyright purposes (Figure 8).

Figure 8

The cloth on the cover as mentioned before is frayed and thin, and the cardboard binding makes the book light to carry, in contrast to the hardcover larger cookbooks of today. The binding is coming undone on the cover and the spine is tearing (Figure 9), but the pages are still held tightly together. While there are only a few tears (Figure 10), there are numerous stains throughout the book.

Figures 9 and 10

There is a bit of foxing—dark stains suggesting moisture (Figure 11). There is also a wide stain at the bottom of the book, noticeable on a few pages. This could be suggestive of some sort of spill (Figure 12). As this book was made to be used in the kitchen, the stains could be from dirty hands in a messy kitchen, oil or water. The pages are also slightly warped when looking at the book from the side, suggestive again of moisture (Figure 7). This could be attributed to the book’s storage, and also to a kitchen environment. Because there are so many unknown variables in a kitchen, and so many ingredients, it is hard to identify what might have caused a stain.

Figures 11 and 12

There are ornamentations throughout the book that serve as spaces between passages (Figure 13). I struggled to find the exact font used as I ran multiple pictures through What the Font but came up with nothing. The font looks like and could be Caslon, invented in the 18th century by William Caslon I, or something related (Coale, 1). The introductory chapter has a small Dickinson stamp, a mark of the archives. There are also written numbers in pencil in the front matter (Figure 14). When I met with the archivist, she was not positive as to what the writing meant, however, it appears to be dates: 1874, 1875, 1858. The dates could be markings from when the book switched hands, when the college acquired it (the exact year is not known as the donor, Charles Coleman Sellers, often gifted and sold the college books from his collection, although he was not alive during the dates listed), or notes from a former dealer of the book.

Figures 13 and 14

Works Cited

“American Frugal Housewife.” Applewood Books,

https://www.applewoodbooks.com/American-Frugal-Housewife-P2007.aspx.

Coale, Brian. “Caslon, When in Doubt, Use Caslon.” Casey Printing – Commercial Printing, Labels & Folded Cartons, 30 Aug. 2013,

Greenfield, Jane. “Glossary of Book Binding’s Structural Evolution.” ABC of Bookbinding a Unique Glossary with over 700 Illustrations for Collectors & Librarians, Oak Knoll Press U.a., New Castle U.a., 1998, p. 109.

“Lydia Maria Child.” Poetry Foundation, Poetry Foundation,

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/lydia-maria-child.

Valente, AJ. “Changes in Print Paper during the 19th Century – Purdue University.” Changes in

Print Paper During the 19th Century, Purdue University , 2010,

https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1124&context=charleston.

Leave a Reply