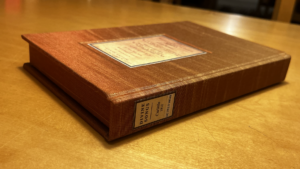

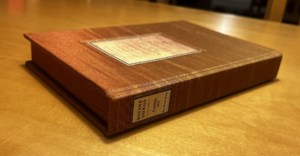

Divine Songs for Children is a little mystery tucked within the Dickinson College Archives. Initially, the book appears ordinary and plain; it resides discreetly within a protective clamshell box. The box is designed to look like a typical hardcover book, it has a spine and the edges (where the pages of a book would be visible) are set deeper in and covered. The boards are covered with orange-brown cloth. As I picked the box up and gazed upon it, I recognized the gold streaks that run horizontally across the cloth. The interwoven gold threads shimmer in the warm light of the archives. Running my hand over the cover I could feel the coarse texture of the fabric. It almost seemed like I could feel each individual thread. The front board of the box, its “cover”, is labeled with a copy of the copyright page. The spine is labeled with the condensed title, “Divine Songs,” the book’s publication year and location, Carlisle 1812, and the call number. From a quick glance at the camouflaged box, nothing hints at the little secret tucked within.

like a typical hardcover book, it has a spine and the edges (where the pages of a book would be visible) are set deeper in and covered. The boards are covered with orange-brown cloth. As I picked the box up and gazed upon it, I recognized the gold streaks that run horizontally across the cloth. The interwoven gold threads shimmer in the warm light of the archives. Running my hand over the cover I could feel the coarse texture of the fabric. It almost seemed like I could feel each individual thread. The front board of the box, its “cover”, is labeled with a copy of the copyright page. The spine is labeled with the condensed title, “Divine Songs,” the book’s publication year and location, Carlisle 1812, and the call number. From a quick glance at the camouflaged box, nothing hints at the little secret tucked within.

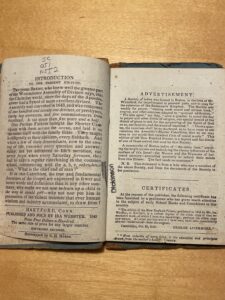

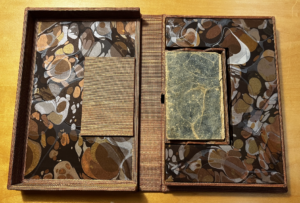

Only upon opening the box did I realize it was not the book itself. To the probable annoyance of my peers, I expect I audibly gasped when inst ead of pages I was greeted with the beautiful metallic marbling of the box’s interior and a surprise palm-sized book tucked perfectly within. Underneath the marbled endpages, the same coarse-threaded cloth covers the inside. The marbling is the same orange-brown tones, now with added silver, bronze, and gold pigments. In the warm light, the metallic tones shimmer terrifically. Now, I am finally facedwith the real Divine Songs for Children. It is a small, unembellished blue book. Surrounded by the splendor of the box, you would expect to be let down by its simplicity, but I was thrilled. In comparison to the clamshell, Divine Songs seems tiny (it is less than half the size: the clamshell box is 21.8cm x 14.7cm x 2.6cm, Divine Songs is 10.25cm x 6.8cm x 0.2cm). It is bound without embellishment: the binding is made of the same paper as the inner pages, there are no boards or endpages, all sewn together with thread. The front and back cover have a single-color faded marbling design. The pages of the book do not feel brittle, as I expected from such an old book. The paper is soft and pliable. It is small, cradled in my hands, delicate and malleable.

ead of pages I was greeted with the beautiful metallic marbling of the box’s interior and a surprise palm-sized book tucked perfectly within. Underneath the marbled endpages, the same coarse-threaded cloth covers the inside. The marbling is the same orange-brown tones, now with added silver, bronze, and gold pigments. In the warm light, the metallic tones shimmer terrifically. Now, I am finally facedwith the real Divine Songs for Children. It is a small, unembellished blue book. Surrounded by the splendor of the box, you would expect to be let down by its simplicity, but I was thrilled. In comparison to the clamshell, Divine Songs seems tiny (it is less than half the size: the clamshell box is 21.8cm x 14.7cm x 2.6cm, Divine Songs is 10.25cm x 6.8cm x 0.2cm). It is bound without embellishment: the binding is made of the same paper as the inner pages, there are no boards or endpages, all sewn together with thread. The front and back cover have a single-color faded marbling design. The pages of the book do not feel brittle, as I expected from such an old book. The paper is soft and pliable. It is small, cradled in my hands, delicate and malleable.

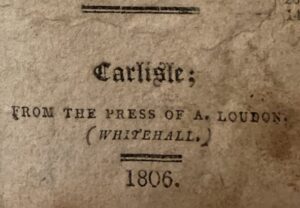

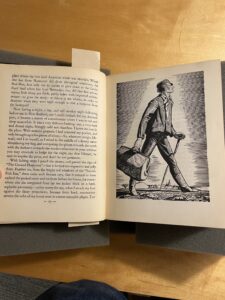

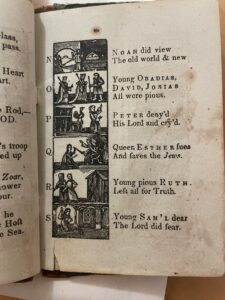

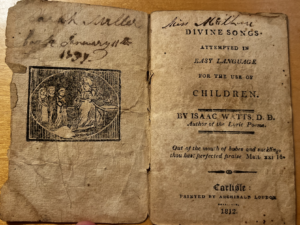

There is a frontispiece on the very first page; it is the only illustration in the book. The frontispiece i s rectangular and off-center (the margins are not evenly spaced on all sides). It depicts three children standing across from a woman sitting in a chair. The illustration uses only black ink; it takes advantage of the negative space to create the children’s faces and their clothes. The copyright page follows. It credits the full title: Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language For the Use of Children by Isaac Watts. This edition was published in Carlisle in 1812 by Archibald Loudon. There is no information about an editor or any additional information about how this book came into print. Sprawled across both pages are handwritten words in script. It is not very legible, the ink has faded

s rectangular and off-center (the margins are not evenly spaced on all sides). It depicts three children standing across from a woman sitting in a chair. The illustration uses only black ink; it takes advantage of the negative space to create the children’s faces and their clothes. The copyright page follows. It credits the full title: Divine Songs Attempted in Easy Language For the Use of Children by Isaac Watts. This edition was published in Carlisle in 1812 by Archibald Loudon. There is no information about an editor or any additional information about how this book came into print. Sprawled across both pages are handwritten words in script. It is not very legible, the ink has faded and bled. It very likely is a signature or a name and a date. The book is twenty-nine pages in total, including the copyright page. The Ten Commandments, “put into a short rhyme” follow the final hymn. The book ends with a summary of the commandments, “With all thy soul love God above, And as thyself thy neighbor love,” and “FINIS”.

and bled. It very likely is a signature or a name and a date. The book is twenty-nine pages in total, including the copyright page. The Ten Commandments, “put into a short rhyme” follow the final hymn. The book ends with a summary of the commandments, “With all thy soul love God above, And as thyself thy neighbor love,” and “FINIS”.

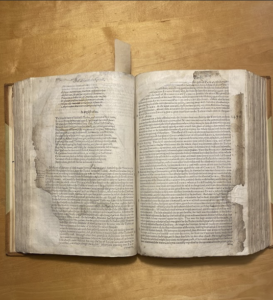

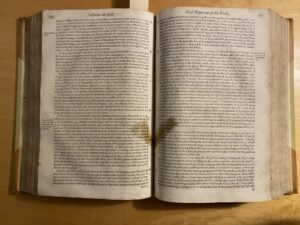

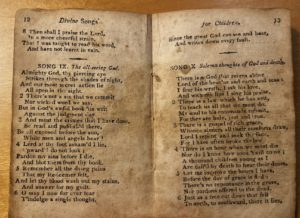

The margins are inconsistent throughout the book. The text is never perfectly centered, and the direction it leans is inconsistent. On the first couple of pages of the book, the text nearly touches the bottom of the page; the upper margin is big, while the bottom margin is near nonexistent. By the end of the book, the text is more centered. The text on page 13 is printed on an angle.

There are signs of wear throughout the book, but the most significant damage appears to be a water stain on the top left of the first page. Throughout the book, the paper is discolored and the edges are chipped. A couple of the pages appear to have burn damage (most noticeably pages 4 and 5). The chipped edges are most notable here and are a dark brown color.

Who owned Divine Songs? Who brought it to the archives? After 200 years the book is still in good condition, so likely it was maintained. It was cared for and valued by someone. But by who?

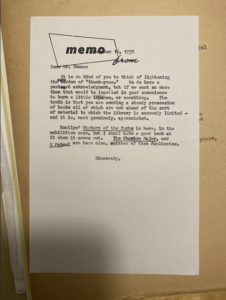

Unfortunately, it is not known how this book found itself in the Archives of Dickinson College. On the inner margin of the 3rd page there is a “Dickinson” stamp. The Dickinson College Archives used to use ink stamps, like the one in Divine Songs; however, their use was discontinued in  1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from Divine Songs. Instead, the call number is written in pencil on the upper margin of the 2nd page. Either this book entered the archives after the use of these stamps was discontinued, or, more likely, it was decided Divine Songs for Children was too small and valuable for the second stamp. From 1927 until the end of the century, donations and acquisitions to the archives were handwritten in ledgers. Often the entries were vague and left out “unremarkable” titles. It would not have been feasible to handwrite everything acquired by the library, still, this unfortunately leaves many books in the archives without records. Divine Songs is not mentioned in these ledgers. Either it was received after 1927 and was not documented specifically or it was received before 1927, prior to the use of ledgers or records at all. We do not know how Divine Songs for Children got to the archives, or about its life before then.

1956. The “Dickinson” stamp is most often accompanied by a secondary stamp, which indicates the book’s inventory number: this stamp is missing from Divine Songs. Instead, the call number is written in pencil on the upper margin of the 2nd page. Either this book entered the archives after the use of these stamps was discontinued, or, more likely, it was decided Divine Songs for Children was too small and valuable for the second stamp. From 1927 until the end of the century, donations and acquisitions to the archives were handwritten in ledgers. Often the entries were vague and left out “unremarkable” titles. It would not have been feasible to handwrite everything acquired by the library, still, this unfortunately leaves many books in the archives without records. Divine Songs is not mentioned in these ledgers. Either it was received after 1927 and was not documented specifically or it was received before 1927, prior to the use of ledgers or records at all. We do not know how Divine Songs for Children got to the archives, or about its life before then.