The Dickinson College Archive’s copy of Divine Songs for Children, printed by Archibald Loudon in 1812, is far from in its pristine condition. It has many signs of wear, along with indications of its importance.

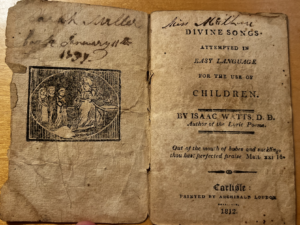

The archives have no records of any previous owners of the small book (it measures a modest 10.25cm x 6.8cm x 0.2cm ). However, it is apparent from markings on the first two pages of Divine Songs that it had at least one owner before its time in the archives. On the very first page of the book, above the frontispiece, someone wrote on the upper margin in script. Overtime, the ink has faded and expanded. This, together with what appears to be water stains on the top left corner of the page, makes it difficult to read the words with certainty. The first line seems to be someone’s name, maybe “Sarah Muller.” Or maybe it’s “Sarah Milter.” Presumably, this “Sarah” was an owner of Divine Songs, possibly even the book’s original owner. Written underneath the name is a date, “January 11th, 1834.” Before the date there is another word, which I believe says, “born on.” January 11th, 1834 is likely Sarah’s birthday, meaning the book might have been a gift for her birth or her baptism.

Given the content of the book, the owners were almost certainly religious; likely they were protestants, as the author of the hymns used in Divine Songs, Issac Watts, was a Protestant minister. We do not know if Divine Songs for Children had a different owner before Sarah or if she was the first. There are twenty-two years between the year written in the book and its year of publication (Divine Songs was published in 1812); unfortunately, there is no information or evidence about where the book was during this time, or of any further owners, before or after Sarah. On the following page, there is more handwriting in the upper margin, however it is illegible.

Besides the handwriting on the first page, there are many other signs of wear and use throughout the book. As I mentioned briefly earlier, there is a water stain on the first page and several other less severe stains on the following pages. The marbling on the cover is worn down, and the edges of the pages have small chips. On the top edge of a couple pages, most prominently page 5, there are what appear to be burn marks. Perhaps someone held the book too close to a candle? There are some areas where the text has faded, but never to the point of illegibility. Based on the wear that Divine Songs for Children has endured, I think it is unlikely that this book was heavily used, especially by a child. It is still, even after 212 years, in very good condition. There is no glaring damage, no tears or rips, no harsh creases. The book was used, yes, it was owned and read. But likely, it spent most of its life tucked away.

It is unclear when Divine Songs for Children was acquired by the Dickinson College Archives. There is no record of when, or how, the book came into the archive’s possession. There is a Dickinson ink stamp on the inner margin of the third page; these ink stamps were used until 1956 whe n the practice was updated. Ordinarily, books with the Dickinson ink stamp also had a stamp showing the book’s inventory number. Divine Songs’ call number is written in pencil on the second page, but there is not a second stamp in the book. Starting in 1927 until the end of the century, acquisitions of the Dickinson College Archive were recorded in handwritten ledgers. Unfortunately, these records were not always comprehensive, and specific titles would get left out. For example, a record would say a title “and three other books” were donated, leaving many texts in the archives without records or histories. Divine Songs for Children is one of these texts. It is not found in the ledgers. Maybe it was acquired before 1927 and before the use of the ledgers? Or maybe it was acquired since but not documented specifically? The book’s past is lost; its history is unknown.

n the practice was updated. Ordinarily, books with the Dickinson ink stamp also had a stamp showing the book’s inventory number. Divine Songs’ call number is written in pencil on the second page, but there is not a second stamp in the book. Starting in 1927 until the end of the century, acquisitions of the Dickinson College Archive were recorded in handwritten ledgers. Unfortunately, these records were not always comprehensive, and specific titles would get left out. For example, a record would say a title “and three other books” were donated, leaving many texts in the archives without records or histories. Divine Songs for Children is one of these texts. It is not found in the ledgers. Maybe it was acquired before 1927 and before the use of the ledgers? Or maybe it was acquired since but not documented specifically? The book’s past is lost; its history is unknown.

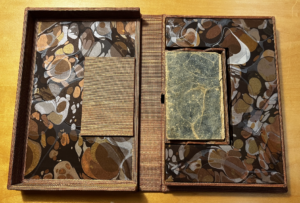

We do know, however, what has happened to Divine Songs for Children since arriving in the archives. In 2020, the Dickinson College Archives worked with a preservation specialist to have a clamshell made for the book. This endeavor was headed by James (Jim) Gerencser, the Associate Dean for Archives & Special Collections. Because Divine Songs was not bound with any boards, it is fragile and susceptible to damage. The clamshell would act as a protective box for the book. The clamshell was custom-made for the book to fit perfectly within it. The clamshell was created by Linda Sale, a preservation specialist from Octávaye. Founded in 2001, Octávaye is a company based in Texas that “provides artifactual restoration and preservation services by adding contemporary approach through art and design,” (as stated on their Instagram, @octavaye). Looking through their profile and a blog post by another client (“Octavaye”), Octávaye specializes in custom protective boxes for books and other documents, without working on the book itself. Octávaye’s boxes are intricate and meticulous, covered with stunning fabrics and hand-marbled paper, often crafted with moving parts to support the book.

Linda Sale, a preservation specialist from Octávaye. Founded in 2001, Octávaye is a company based in Texas that “provides artifactual restoration and preservation services by adding contemporary approach through art and design,” (as stated on their Instagram, @octavaye). Looking through their profile and a blog post by another client (“Octavaye”), Octávaye specializes in custom protective boxes for books and other documents, without working on the book itself. Octávaye’s boxes are intricate and meticulous, covered with stunning fabrics and hand-marbled paper, often crafted with moving parts to support the book.

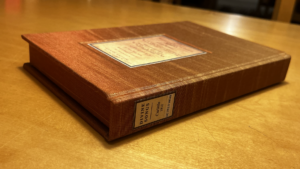

The clamshell for Divine Songs was designed to appear like a typical book from the outside. There is a recreation of the title page on the “cover” ofthe clamshell, and on the “spine” is a label with the title, Divine Songs, and the book’s call number. The clamshell is significantly larger than the small Divine Songs (the clamshell’s dimensions are 21.8cm x 14.7cm x 2.6cm). Along with the clamshell’s firmer makeup, its larger and more standard size allows Divine Songs for Children to be easily and safely shelved alongside other books in the Dickinson College Archives. In total, the creation of the clamshell box cost $350.00. This book is a valued piece of the archives, based on the effort and money put into preserving it.

Works Consulted/Cited

“Octavaye.” What’s in Woodson, 17 Nov. 2020, https://woodsononline.wordpress.com/tag/octavaye/.

“Octavaye-Preservation Instagram Profile.” Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/octavaye/?hl=en. Accessed 13 Dec. 2024.

Ossoinig, Wendy. “OCTAVAYE LinkedIn.” LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/company/octavaye/. Accessed 13 Dec. 2024.

“Watts, Isaac.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc, 2020.