Confession Alert: I found my dream home, or town rather. Sutera, Sicily. A tiny town literally on the side of a mountain smack dab in the middle of Sicily. The views of the island are better than you could ever imagine. Driving up to the town and wandering around (and maybe getting a little lost) makes you feel like you’re in a fairytale. I couldn’t believe my eyes. The quaint houses, windy streets and tiny random piazzas are picturesque beyond belief. I may have been slightly conditioned to love  Sutera because I listened to schmaltzy Italian pop music that romanticizes Italy to the max for me, but still this town is special. The people were eager to talk to us and share their story.

Sutera because I listened to schmaltzy Italian pop music that romanticizes Italy to the max for me, but still this town is special. The people were eager to talk to us and share their story.

After the beautiful two hour train ride from Palermo, a 15 minute taxi ride straight up the side of the mountain and a few moments to pause, gawk and drop our jaws at the incredible scenery, we met up with the president of the local council, who happens to be the daughter of the last mayor of Sutera, and a few other people (many named Pino). Everyone knows and/or is related to everyone there so as we walked around we kept learning that this vegetable and fruit cart owner was so-and-so’s aunt or that the driver of that car was the Mayor’s wife. Eventually, after figuring out a tentative schedule for the day, we headed into town to meet the Vice Mayor.

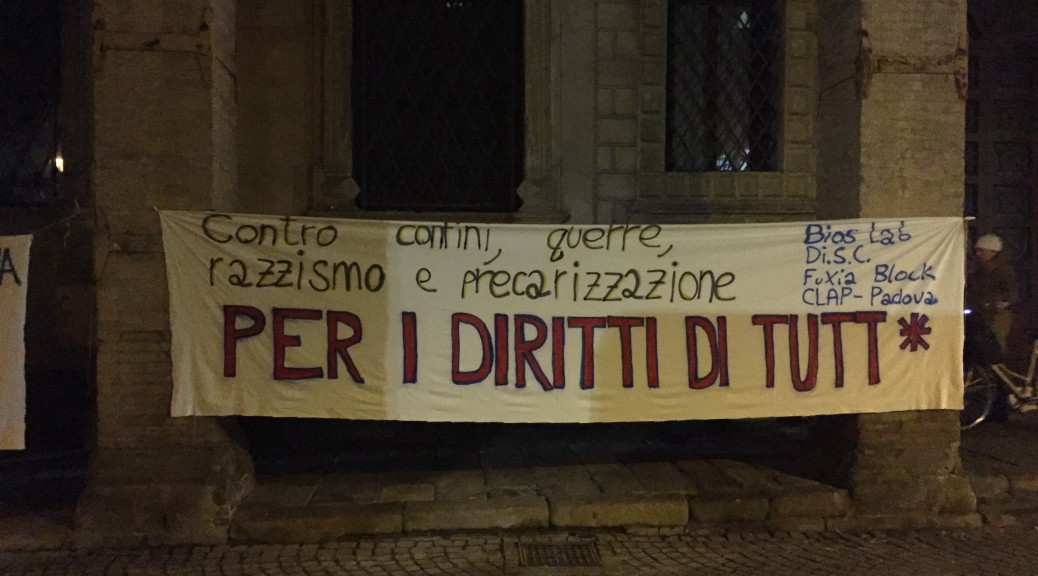

Sitting circled around an impressive wood-carved desk, the mosaic team and I interviewed the Pino Landro, the Deputy President of Sutera and the leader of the immigrant integration program organized by the commune, Santina Lombardo. The Deputy, a middle-age d man and retired teacher, proud to talk about and tour his village, began by explaining Sutera’s program for immigrants to us. He said that currently, there were currently 30 immigrants living in the commune, all of which had been processed and distributed by Roman decree, based on which cities had available space. This process is part of an initiative called SPRAR, “Il Sistema di protezione per richiedenti asilo e rifugiati” or the system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees. Of the 500 programs like Sutera’s that exist, Landro proudly said that 90 are in Sicily. Perhaps this is because southern Italians and Sicilians can commiserate, having a reputation as being migrants themselves, frequently traveling to northern Italy where it is more industrialized. Sutera, Landro explained, used to be a place that just send people away however now it has transitioned in one that receives people.

d man and retired teacher, proud to talk about and tour his village, began by explaining Sutera’s program for immigrants to us. He said that currently, there were currently 30 immigrants living in the commune, all of which had been processed and distributed by Roman decree, based on which cities had available space. This process is part of an initiative called SPRAR, “Il Sistema di protezione per richiedenti asilo e rifugiati” or the system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees. Of the 500 programs like Sutera’s that exist, Landro proudly said that 90 are in Sicily. Perhaps this is because southern Italians and Sicilians can commiserate, having a reputation as being migrants themselves, frequently traveling to northern Italy where it is more industrialized. Sutera, Landro explained, used to be a place that just send people away however now it has transitioned in one that receives people.

This is fitting because the name ‘Sutera’ comes from an ancient word meaning ‘salvation’ or ‘welcoming.’ Many years ago, the city emulated its image today, as a city accepting of desperate migrants. In addition, during the era of feudalism in Italy, Sutera remained autonomous and for this they are proud; thus, the village highly regards and continously tries to instill the power of autonomy in its inhabitants. When asked about their thoughts on economic vs. political or cultural migrants, both narrators said they saw no difference. Landro explained that the same issues that cause war cause poverty, thus both categories are deserving of help. While such is a progressive view among Italians, this has clearly been their attitude for a long time. In fact, it seems to have influenced officials on the Italian mainland. In the official document that described SPRAR’s purpose it reads, “ a network of local authorities that se t up and run reception projects for people forced to migrate,” thus removing the need to distinguish between the push factors by not specifying why those people were forced to migrate.

t up and run reception projects for people forced to migrate,” thus removing the need to distinguish between the push factors by not specifying why those people were forced to migrate.

Sutera provides a good example of the situation in which many Sicilian municipalities are finding themselves. While the European Union provides the programs with funding for the migrants’ housing, finding those houses in the first place is not a challenge. Most of the immigrants in Sutera live in homes abandoned by families and youths searching for education and job opportunities elsewhere. Many Suterans used to emigrate to the United States and later to Germany. This trend was so common that the commune now has three “twinning” villages in Germany with whom them share cultural traditions and facilitate communication between their respective schools. Mass emigration from Sutera seemed like a sensitive topic for the Deputy, who described a situation in which the the diaspora of youths had left an old and dying population. He continued, saying that there are only around 12 births a year, a figure lower than the death rate. One of the teachers later commented on how they all celebrated each birth in the town and she could name all the children: Destiny, Divine…. Who had been born in the last year. This suggests Sutera had alternative reasons for accepting immigrants, besides a desire to help the displaced. With an elderly population who likely struggle to navigate the village’s slanted – indeed vertical – landscape, there was probably an increasing need for mobile people to perform jobs around the commune and farms. Therefore bringing in a youthful and job hungry population was crucial for the livelihood of their economy. A number of Romanian women have come to Sutera to help care for the elderly as badante. Other more transnational migrants are welcome to stay as long as they want in Sutera but they must stay at least as long as it takes for their application for asylum to be processed. As we learned earlier in our trip, this can take as long as two years.

In such a small population, around 1500, it has been easier for immigrants to integrate. They themselves make up just 9 families, 30 people total, 12 of which are children. Lombardo talked about this, describing some of the ways the native and foreign population have come together. Most notably was the sharing of traditions and celebrations. In fact, there is a holiday each year during which the migrants make their traditional foods and clothing and the whole commune comes together to celebrate. Interestingly, the woman used the verb ‘infect’ to describe how the foreign cultures meet the native one. This verb tends to have a negative connotation in English, whether or not she meant it that way was unclear. She did, however, tell us that many of the elderly population were not open to taking in migrants at first. The small population luckily has remedied this situation, for now since there are so few births, any newborn is treated like the village’s collective grandchild.

The arrival of migrant youths to Sultera was particularly important since, with the declining population, there were not enough children and resources to support the school. In fact, it had to close for a couple of years. With the external support for immigrant programming and the increase in immigrant children, it meant the school could reopen – another major benefit for the community. The commune places a great importance on their schooling. One aspect in particular that Landro and Lombardo discussed was their focus on encouraging migrants students to tell their stories. Teachers they said, were taught to support their foreign students in talking about their voyages and adversity. Never in an intrusive way for course, but with the student’s best interest at heart. In addition, there were councilors available for the migrant children as well as for the Suteran adults who may be unprepared to hear such traumatic stories from the students. These services are paid for by the program’s Roman headquarters.

Our interview with these two individuals gave us great insight into how integration can be done successfully. After visiting a number of places where this had not yet happened, it was inspiring to speak with some individuals who were on the right path. While there are still some troubles facing the program, since jobs are still scarce, Sutera still provides a welcoming and safe temporary home.

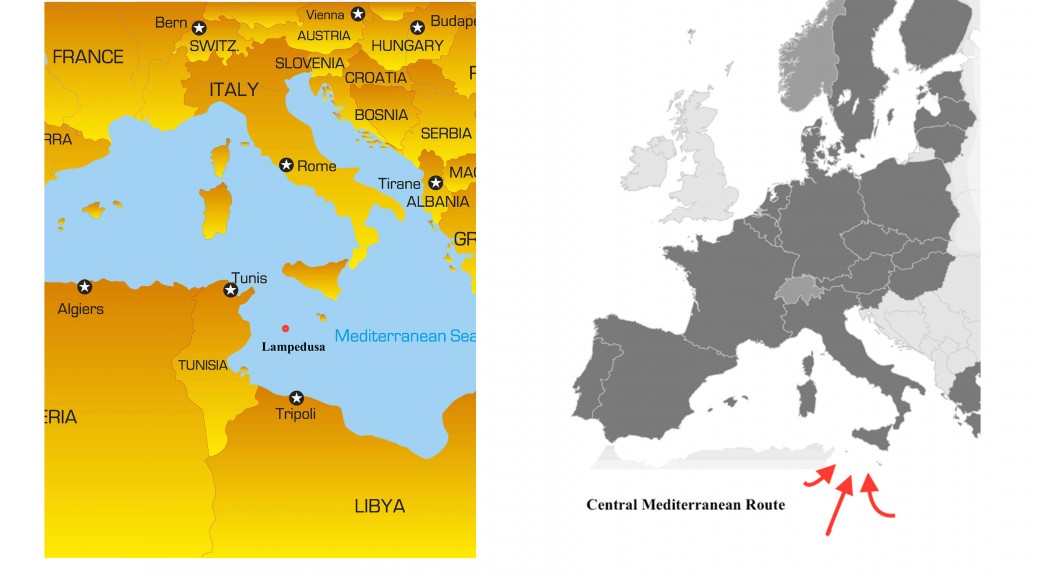

At the school, “Scuola Primaria Senatore G. Mormino”, we were curious to see how the children of immigrants were being integrated into the school. There are about 12 refugee students at the school, out of a hundred students total. When you first walk into the school, there is a large photo of a rickety boat taking refugees and migrants from Africa to Lampedusa. An unusual visual greeting as you walk through a school’s front door, but it’s symbolic for the community. It’s a sign of hope as the refugee children attending classes there have brought the school back to life after multiple waves of emigration from the area. The image is also a powerful reminder of Sutera’s history as a place of refuge, as evidenced by its name.

We started in the kindergarten classroom. Wow, were they all adorable! Plus they spoke Italian, which is obvious, but always such a shock to my ears because I am so used to hearing little kids speak in English! When we were there, they were on a break of sorts for having worked hard and attentively all morning, so they were rewarded with TV time, something that shocked me actually. I never watched cartoon TV shows in all of my years of public education.

One girl from Pakistan, who had been there for almost a year, clung onto her teacher for the whole 20 minutes we were there. She was the only child of immigrant parents in her class of about 15. Her older brother has adapted more quickly . We were pained to leave them, but needed to keep on track and go visit the other grades. The first classroom we stopped in was a class of sixth graders. We did a quick introduction of names and why we were visiting and then learned all of the students’ names. Patricia, one of the students, was called up to talk to us because she has good English skills. She is the daughter of two Nepalese refugees. We later found out that the reason she is so good at English is because her father was an English teacher at an all-English high school back in Nepal.

As we passed through the rest of the classrooms, Patricia helped introduce all of the students and then tell them why we were there. Her Italian was very good – and she had only been in Italy for four months! Her parents had to quickly escape from Nepal and were able to bring her to Italy after they had been here for 2 years. Meanwhile Patricia lived with her grandmother and experienced the devastating earthquake. I was so impressed with her! 11 years-old, great English, warm personality, and practically knows Italian already. It’s amazing how agile brains are when you’re young. I’ve been so fascinated with the language aspect of this trip. Language really affects what happens in someone’s life. Patricia is lucky because she is able to learn Italian while young and in school. Migrants who come to Italy looking for work rarely find the occasion to learn Italian and therefore cannot become part of society as easily. Language can both create and breaks so many barriers!

Visiting the school in Sutera was a cool way to gain more perspective on young immigrants and refugees in the educational system. It was also interesting to compare it to the Besta School in Bologna. Each school is doing the best with what they have. The Besta school may have better access to resources and a higher student population, but Sutera’s school is still thriving thanks to the influx of immigrant children and the community’s dedication to education, integration and the future.

After lunch we ended our day in Sutera with Patricia’s (one of the students we met at the school) family. She lives with her dad and mom, Siam and Pragia, who graciously invited us into their home to talk with them about their personal migration story from Nepal and their experiences living in Sutera. The former mayor, Gero Difrancesco, of Sutera took us to their house and stayed during our talked with them because he was a good friend of the family. When we walked into their house it immediately felt like a home, you really got the sense that a family lived here. The house was warm and smelled amazing with a mix of different smells from spices. They had family pictures and decorations up on the wall. They got chairs for us to all sit with them in their living room and Patricia and her mom brought us traditional Nepalese crackers and tea to eat and drink (they were both delicious!).

We sat down and started talking with them, mostly the dad and Gero, as Patricia and her mother kept coming in and out bringing us more food. We learned that they are the only Nepalese family in Sutera The dad and mom had been in Sutera for the past two years, but Patricia only had come to Sutera about four months ago. That was astonishing to hear as Patricia seems to know Italian so well already and seems to be very well adjusted in school with many friends. Her mom and dad are also learning Italian through classes offered to them. We learned that the her mom and dad left Nepal due to ethnic violence between the people in the mountains and the people in the plains. The father was an English teacher in Nepal and also faced threats since many did not approve of his teaching.. They had to leave Nepal very quickly to escape to safety. Patricia stayed behind to live with mom’s family when her parents left before her. When the parents left Nepal they were telling us that they did not know where they would end up. As the dad put it “people of poor countries have no destination,” they must go where they can.

When Patricia finally came to Sutera to be reunited with her family she had to fly all by herself 22 hours to make it to Italy.. The whole community of Sutera was anxiously awaiting Patricia’s arrival. This shows the nice sense of community we had felt and seen in Sutera the whole day we were there. Patricia’s family has really valued this sense of community that Sutera has given them these past two years but the father said, it can also feel like prison. Given our own observations, we guessed this was due to the isolation of the mountain town. With only one bus going up and down the mountain a day and being a two hours train ride from the capitol, Sutera feels very removed. Furthermore, being on a hill, the buildings have cleverly been built adjusting to the slant. The unfortunate result of this is that the close rows of houses feel as though they are leaning inwards. As previously mentioned, there is little social mobility due the limited job opportunities thus, this potentially monotonous life style in place whose physically layout making the inhabitants feel walled in can understandably make them feel imprisoned. Since Sutera was so open to taking in migrants they were also very open to experiencing their different cultures. One way Gero and Patricia’s family became such good friends was through inviting each other into their homes and sharing their different cuisines and cultures with each other. Sutera has many festivals where people make various foods and share their different cultures.

We also talked with the family about if they think they will stay in Sutera. They told us that it is too difficult at this time to ever return to Nepal. They have loved their time in Sutera, but there are also some negative aspects they have to deal with. Since Sutera is on top of a mountain you need a stable form of transportation to get anywhere, but there is only one bus a day in the morning. This makes it really hard to get anywhere and it can feel really isolating to not be able to have access to leave Sutera when you may want to, or need to. Also the job opportunities are extremely limited in Sutera, and if you do not have a car to travel for work it can be really hard to survive. The decision to stay in Sutera, or move on somewhere else will be something they will need to figure out as time goes on.

As we leave Sutera we are left with the amazing people we have met and interacted with in this extraordinary little town. We are also left with the most amazing views of the whole trip! Sutera is a beautiful town full of rich community that is pushing it to continue to thrive. It was such a memorable experience that we will all cherish!

-Hyla, Ingrid, Paige

and during a short performance break, he was briefly interviewed by Karl Hoffman about his work as mayor and his open opposition to the Mafia power within the city. Mr. Orlando particularly mentioned that the funds collected from the sale of properties seized from the criminal organizations are used to benefit social programs, including projects connected to migrants.

and during a short performance break, he was briefly interviewed by Karl Hoffman about his work as mayor and his open opposition to the Mafia power within the city. Mr. Orlando particularly mentioned that the funds collected from the sale of properties seized from the criminal organizations are used to benefit social programs, including projects connected to migrants.

Sutera because I listened to schmaltzy Italian pop music that romanticizes Italy to the max for me, but

Sutera because I listened to schmaltzy Italian pop music that romanticizes Italy to the max for me, but  d man and retired teacher, proud to talk about and tour his village, began by explaining Sutera’s program for immigrants to us. He said that currently, there were currently 30 immigrants living in the commune, all of which had been processed and distributed by Roman decree, based on which cities had available space. This process is part of an initiative called SPRAR, “Il Sistema di protezione per richiedenti asilo e rifugiati” or the system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees. Of the 500 programs like Sutera’s that exist, Landro proudly said that 90 are in Sicily. Perhaps this is because southern Italians and Sicilians can commiserate, having a reputation as being migrants themselves, frequently traveling to northern Italy where it is more industrialized. Sutera, Landro explained, used to be a place that just send people away however now it has transitioned in one that receives people.

d man and retired teacher, proud to talk about and tour his village, began by explaining Sutera’s program for immigrants to us. He said that currently, there were currently 30 immigrants living in the commune, all of which had been processed and distributed by Roman decree, based on which cities had available space. This process is part of an initiative called SPRAR, “Il Sistema di protezione per richiedenti asilo e rifugiati” or the system for the protection of asylum seekers and refugees. Of the 500 programs like Sutera’s that exist, Landro proudly said that 90 are in Sicily. Perhaps this is because southern Italians and Sicilians can commiserate, having a reputation as being migrants themselves, frequently traveling to northern Italy where it is more industrialized. Sutera, Landro explained, used to be a place that just send people away however now it has transitioned in one that receives people. t up and run reception projects for people forced to migrate,” thus removing the need to distinguish between the push factors by not specifying why those people were forced to migrate.

t up and run reception projects for people forced to migrate,” thus removing the need to distinguish between the push factors by not specifying why those people were forced to migrate.

“Born to take care of oneself from destruction.”

“Born to take care of oneself from destruction.”