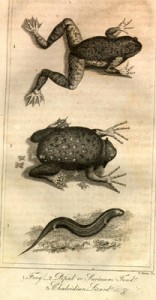

Amphibians, like those at left from Goldsmith‘s Animated Nature proved particularly ambiguous to naturalists and the general public. Here were creatures that reproduced from eggs and milt, but then grew through several remarkably various stages: some tadpoles into water dwelling-frogs, other tadpoles into land-dwelling toads, strange gilled-creatures that sometimes lost their gills and sometimes did not, salamanders that could regrow entire limbs and tails if they were cut off. The Surinam toad (middle left) had young that gestated in the tiny pockets on the mother’s back, after the eggs were pushed in by the male, and then they emerged like so many terrifying alien parasites. Galvani used frogs for his early experiments with animal “electricity.” The terrors of dead frog legs twitching would eventually emerge in Dr. Frankenstein’s shuddering, nameless monster. It has become clear in recent decades that amphibians are among the most important of the canaries-in-the-mine, so-called “warning” species whose delicate constitutions indicate when specific environments–or precise Darwinian niches–are in danger, either from toxins in the system (chemical, atmospheric, genetic) or from pressures (population, ecosystem balances) that had never been understood prior to the development of modern ecological biology. When frogs start to show up with extra legs, or salamanders with no eyes or no tails, it is clear that something is wrong in a living system that can otherwise appear healthy. Amphibians are also important because their regenerative capacities–they can regrow entire limbs down to the fingers–hold promise for research into developmental biology higher up the evolutionary scale (homo sapiens, for example).

Amphibians, like those at left from Goldsmith‘s Animated Nature proved particularly ambiguous to naturalists and the general public. Here were creatures that reproduced from eggs and milt, but then grew through several remarkably various stages: some tadpoles into water dwelling-frogs, other tadpoles into land-dwelling toads, strange gilled-creatures that sometimes lost their gills and sometimes did not, salamanders that could regrow entire limbs and tails if they were cut off. The Surinam toad (middle left) had young that gestated in the tiny pockets on the mother’s back, after the eggs were pushed in by the male, and then they emerged like so many terrifying alien parasites. Galvani used frogs for his early experiments with animal “electricity.” The terrors of dead frog legs twitching would eventually emerge in Dr. Frankenstein’s shuddering, nameless monster. It has become clear in recent decades that amphibians are among the most important of the canaries-in-the-mine, so-called “warning” species whose delicate constitutions indicate when specific environments–or precise Darwinian niches–are in danger, either from toxins in the system (chemical, atmospheric, genetic) or from pressures (population, ecosystem balances) that had never been understood prior to the development of modern ecological biology. When frogs start to show up with extra legs, or salamanders with no eyes or no tails, it is clear that something is wrong in a living system that can otherwise appear healthy. Amphibians are also important because their regenerative capacities–they can regrow entire limbs down to the fingers–hold promise for research into developmental biology higher up the evolutionary scale (homo sapiens, for example).

Amphibious Thinking

This entry was posted in More Topics and tagged amphibian, frog, salamander, toad. Bookmark the permalink.