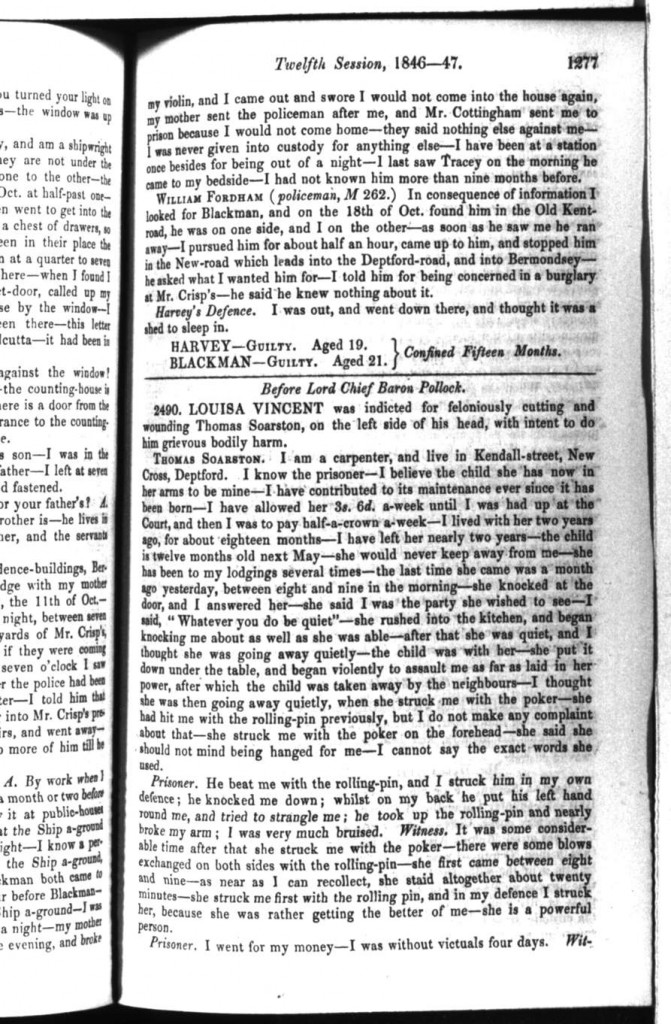

Nothing beats a good, old fashioned, Victorian sex scandal. This court case from the Old Bailey follows the testimony of Louisa Vincent, a woman on trial for attacking her former lover and father of her illegitimate child. The proceedings include testimony from both the defendant and her alleged victim.

I chose this text for my Victorian Queer Archive project because it includes so many details that would scandalize, yet intrigue, a Victorian audience. The subject matter is taboo and serves to queer assumptions about Victorian society’s prudishness and aversion to sex, especially given the public nature of trials in the 19th century in London. Furthermore, the “queer” nature of the subjects–poor, criminal, sexual, unmarried–highlights that the figures that inhabit the edges of Victorian society (and who receive public attention) are not always the pure, innocent, and gentlemanly ideal.

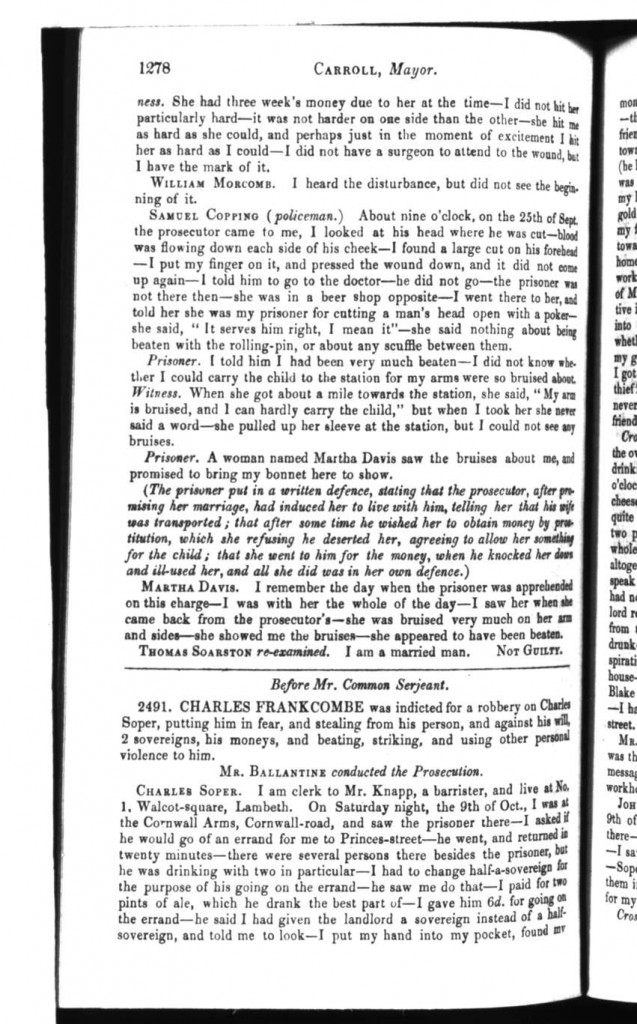

In his text “Sex, Scandal, and the Novel”, William A. Cohen suggests that sex scandals publicly reveal sexual information and knowledge that might otherwise be best kept secret. The lewd sensationalism of crime and passion can be seen in this transcription. For example, Louisa Vincent (Prisoner) and Thomas Soarston (Witness/victim) both argue over who initiated the fight. Soarston accuses Louisa of attacking him first, while Louisa accused him of not providing for their child and of starving her (“I was without victuals four days”). The “he said/she said” nature of the testimony is something that is seen in contemporary sex scandals as well. Curiously, Louisa is on trial despite evidence that Soarston also hit her. I would suggest that this is because Louisa is obviously an outcast from Victorian society: the presence of an illegitimate child marks her as impure and tainted. In addition, the implication that she is a prostitute (and Soarston her pimp) further alienates her from polite Victorian society. On the other hand, illegitimate children and infidelity in general were tolerated more for men, therefor Soarston’s breaches of Victorian norms do not reflect as poorly upon him.

Cohen also mentions that the “unspeakability” of the sex scandal which actually serves to create discourses that reinforce the notion of sex as taboo. Instead of the sex scandal quashing discussions of forbidden sex, it actually creates the opposite effect. For instance, trials at the Old Bailey were a form of public entertainment. These trials, however, still made use of heavily coded language in order to avoid transgressing too heavily. This is evidenced in the italicized explanation of the testimony:

“The prisoner put in a written defence, stating that the prosecutor, after premissing her marriage, had induced her to live with him, telling her that his wife was transported; that after some time he wished her to obtain money by prostitution, which she refusing he deserted her, agreeing to allow her something for the child; that she went to him for the money, when he knocked her down and ill-used her, and all she did was in her own defence.”

In this excerpt alone, there is mention of forced prostitution, infidelity/polygamy, and even of rape (“he knocked her down and ill-used her”). None of these transgressions are openly named, instead this excerpt employs language that Cohen calls the “richly ambiguous, subtly coded, prolix and polyvalent” that is inherent in the sex scandal.

Finally, while “scandal teaches punitive lessons”, indicating its moralizing nature, sex scandals still incite in a Victorian audience the possibility of transgressing and the potential for the queer to enthrall and thrill.

Works Cited

Cohen, William A. “Sex, Scandal, and the Novel.” Sex, Scandal, and the Novel. Victorian Web, n.d. Web. 10 Nov. 2016.

http://vqa.dickinson.edu/shortstory/louisa-vincent-breaking-peace-wounding-25th-october-1847

LOUISA VINCENT, Breaking Peace Wounding, 25th October 1847. London’s Central Criminal Court. 25 Oct. 1847. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey Online. Web. 10 Nov. 2016.

Save